How Simon Lupton and Jake McBride brought back Freddie Mercury for new Queen video

Director Simon Lupton and Jake McBride of Animind Studios describe how they created a new music video for Face it Alone, Queen's "lost song" that's been sweeping the globe this autumn.

Legendary rock band Queen has a new song out, and it's something pretty special. Face It Alone was originally recorded over 30 years ago by all four members of the original group – Brian May, John Deacon, Roger Taylor and Freddie Mercury – for their 1989 album The Miracle. But it never made it onto the record and was never released. This year, however, it's finally seen the light of day.

Not surprisingly, this previously unheard track has gone down a storm around the world. On the day of its digital release, it became the most downloaded song in the world for five days in a row and went to number 1 on the iTunes download charts in 21 countries. It's one of six unreleased tracks featured on The Miracle Collector's Edition box set, which goes on sale today (Friday 18 November).

But while the success of Face It Alone has been no big surprise, its release did pose a few problems. Such as: how do you make a video for a singer who's no longer around?

The concept

Director-producer Simon Lupton, who teamed up with Jake McBride of Animind Studios for the project, was clear in his mind about what the video needed to achieve.

"The intention was to create, despite how the lyrics might be interpreted, an upbeat video that celebrated the fact that the period when this song was recorded was one of the most prolific and cohesive in the band's history," he explains. "Having had a two-year break and made the decision to share writing credits, Queen refer to the recordings of The Miracle and the subsequent Innuendo albums as bringing them closer together than they had been since the early days."

The interpretation of the lyrics for the purposes of this video, he explains, is that when something catastrophic occurs in your life, your instinct is to surround yourself with what is dearest and most important to you. "While the verses talk about something' exploding inside' and essentially tearing your life apart," says Simon, "the chorus is a triumphant response of finding the strength to take control and 'master' your situation."

In this instance, he explains, immersing himself in his work and surrounding himself with his band-mates gave Freddie that control. "Of course, in the end, you have to face it alone – but the people around you can help how you face it."

With that in mind, Simon wanted to re-create the place where Freddie and the band found the environment to be at their best: Mountain Studios in Montreux. (If you haven't seen it yet, you can watch the finished video below.)

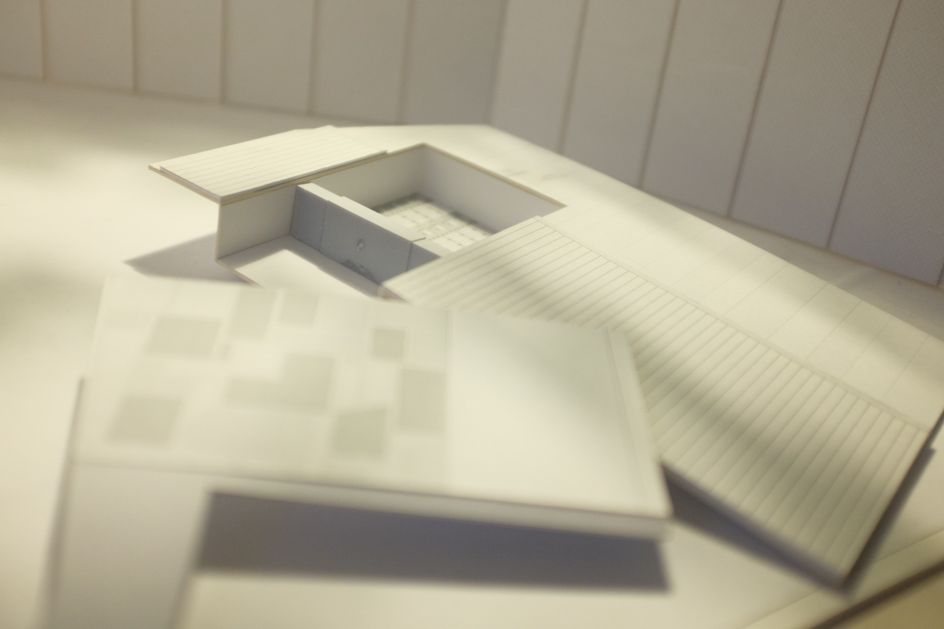

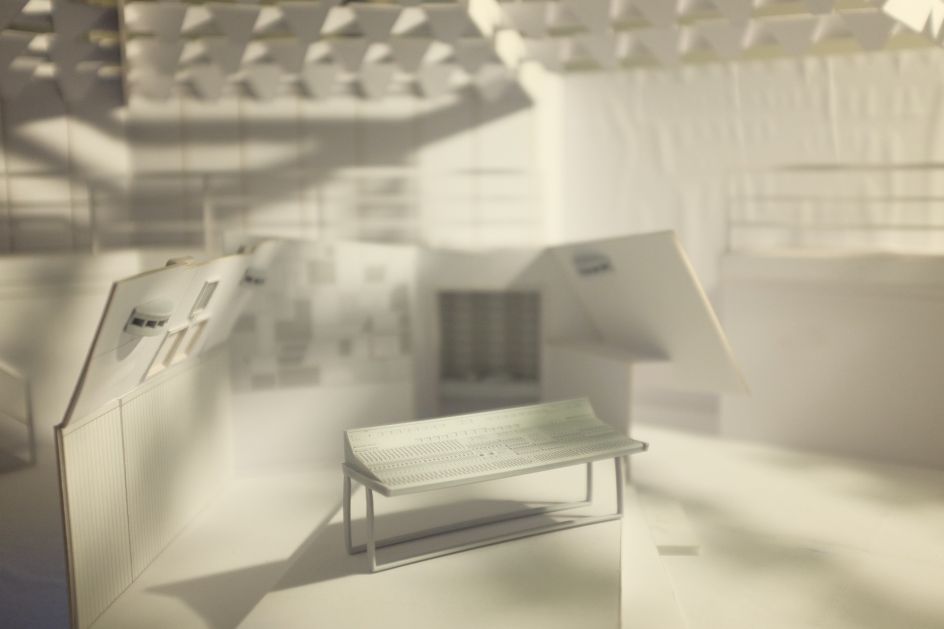

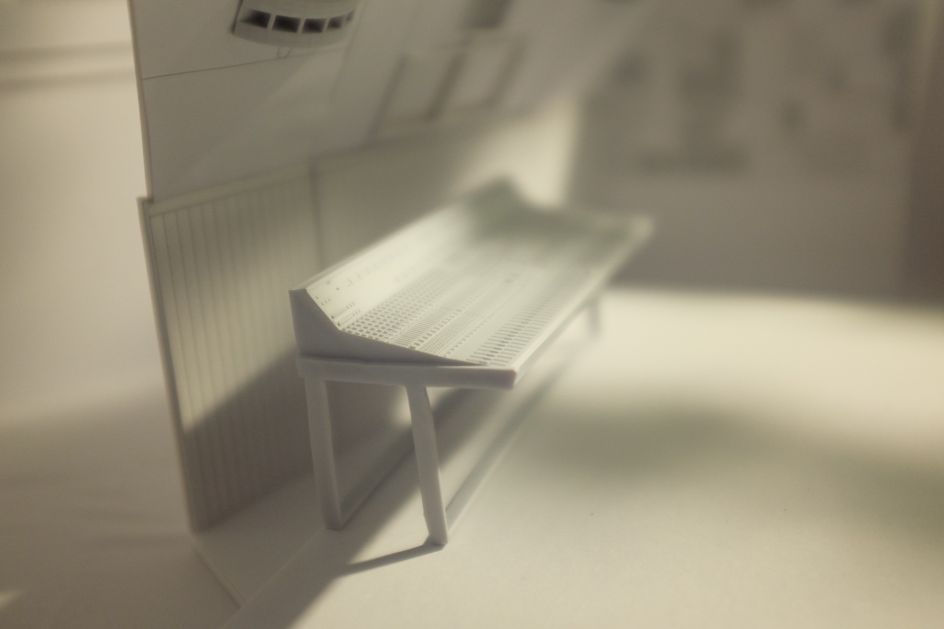

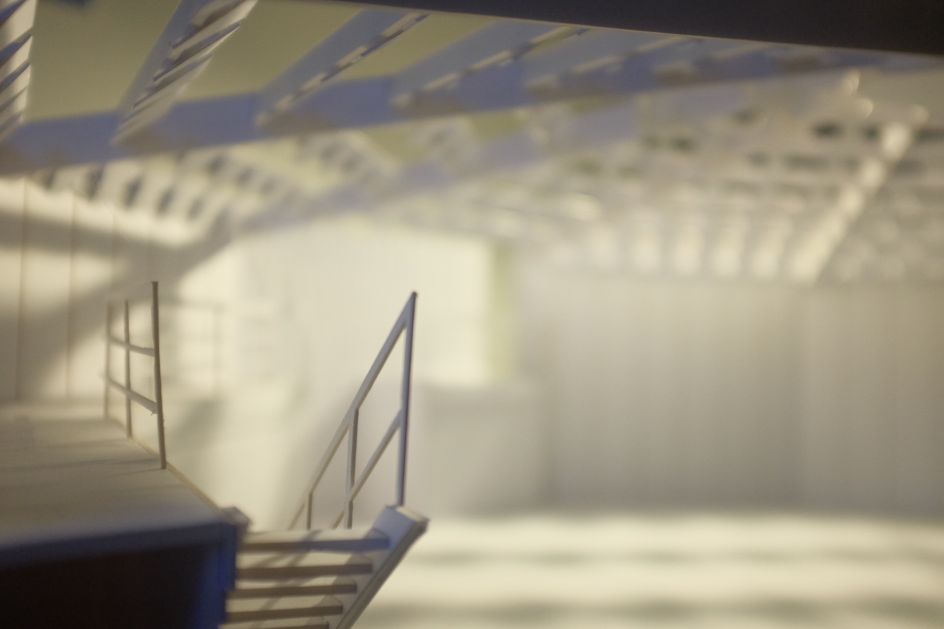

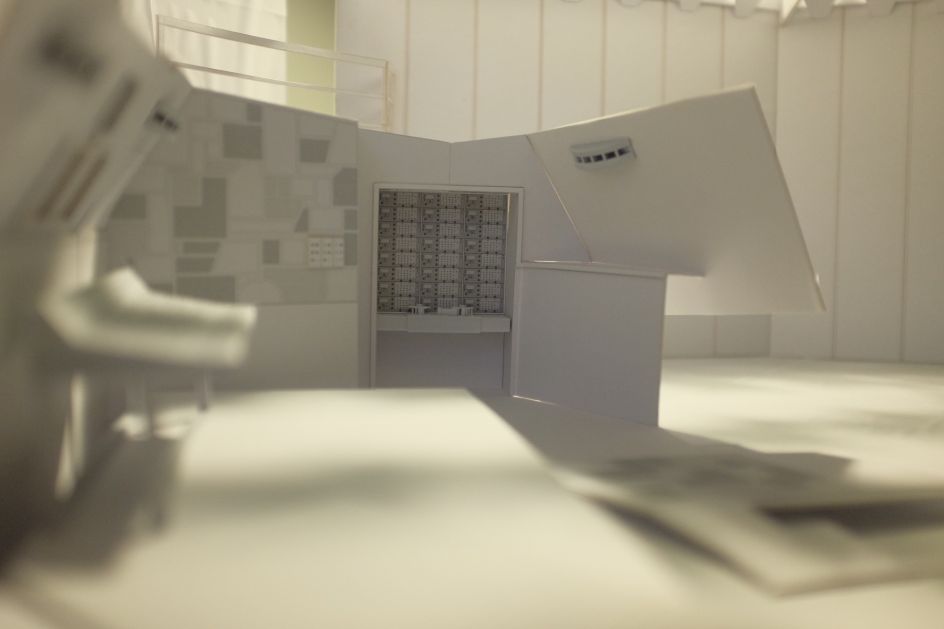

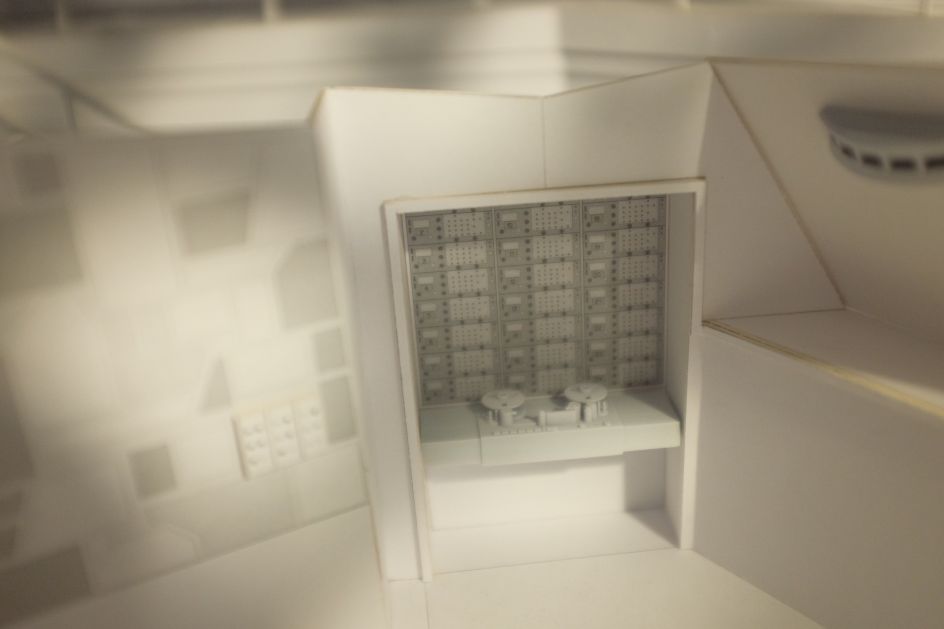

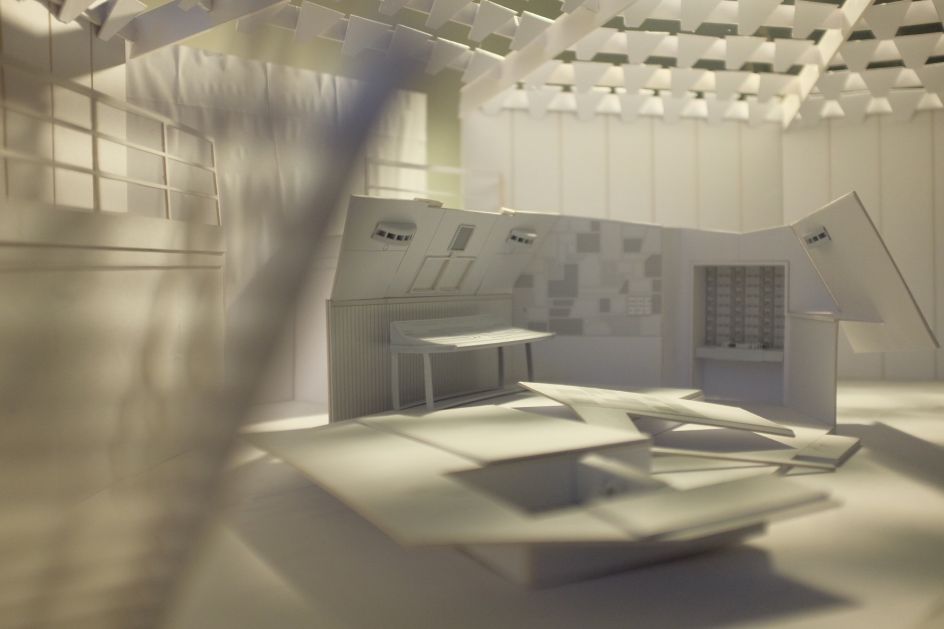

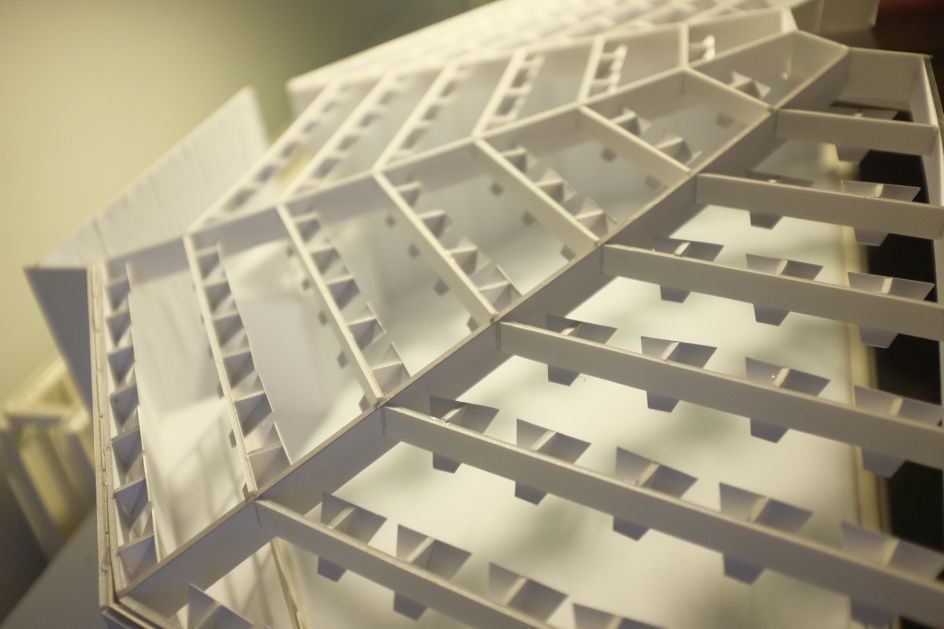

The video starts in a sparse, white 3D model of the studio built especially for this promo. Miniature statues of the band represent a moment from 1989 when they recorded the Miracle album. Images from the songs they were making at the time are projected onto the walls behind them. We then move through the corridor into the control room, with more images appearing on the walls and the monitors.

All the time, a mysterious, malevolent cloud-like effect is encroaching on the shots – growing bigger and threatening to take over the whole image. However, as we hit the chorus, the video bursts into light and life, banishing the 'cloud', and we transition from the 3D model into the actual control room.

After the guitar solo, a silhouette of Freddie appears and takes us out into Montreux. Joined by the rest of the band, he appears first on the exterior of the studio building (the Montreux Casino) and is followed by Lake Geneva and the building where Freddie lived, in the top-floor flat. All places that meant a great deal to him during this period.

As before, images of the band working closely together are projected. As the song draws to a close, we return to the studio model and miniature statues. Images of the band at work continue to echo around before the final 'Face It All Alone'.

It's an incredible video, and we wanted to learn more about how it was made. Read on to hear more from Simon and Jake about the creation process.

You've both worked with Queen before..., but this project was still pretty special, right?

Simon: Yes, I've been fortunate enough to work with Queen for the last 20 years, and during that time have been involved in several promo video productions. However, Face It Alone was still an incredibly special project to be a part of. First and foremost, as a fan, hearing what was essentially a brand-new Queen song was nothing short of spine-tingling. Knowing the four of them, Brian, Roger, Freddie and John, had worked on this together was special. And while getting to listen to Freddie singing in his prime once again was incredible, having him deliver a song with such power and emotive lyrics, particularly now knowing what he was going through at the time, really was something else.

Being asked to create a video to accompany it was a huge privilege and also a massive responsibility. I knew Queen fans worldwide would experience the same emotions and feelings that I had hearing it for the first time – and if that was going to be as they watched this video, the pressure was on to create something that did it justice.

Jake: I've had the pleasure of working with Queen many times over the years. These opportunities stemmed from publishing a passion project onto YouTube over eight years ago; an animated lyric video for Know Me Well by Roo Panes, around the time I started studying Film at Falmouth University.

Emma Donoghue, music manager at Queen Productions, had seen the Roo Panes animation and got in touch to discuss a similar project for one of Brian May's solo tracks. After a few years of continued work with Brian and Roger, regularly pinching myself, I was connected to Simon. He's brought a plethora of amazing Queen projects to my door, including this one. Simon has a wealth of knowledge across the board, so collaborating with him on creative projects is especially exciting and rewarding.

How did you get started on the project?

Simon: Our principle consideration was that the music must be the most important aspect. Of course, that's true of any Queen video, but in particular, this one felt like nothing should detract from the music.

At the time of recording, no footage was taken of the band working on this song, and it was never performed live – so we didn't have any imagery of Queen that could synch up perfectly with the music. At the very early stages, we also ruled out the idea of filming new material with Brian May and Roger Taylor. This song was rooted in 1989, so footage of the band now wouldn't be appropriate. So, this was always going to be an archive-based piece – but I was keen this wouldn't just be a montage of old familiar footage, that somehow we could bring this more to life.

My first port of call was Jake – someone I had worked with on previous Queen videos and whose skill and creative ideas I trust. I explained that this would be an archive-based video but that I wanted to frame that footage in an interesting and meaningful way. I liked the idea of projecting it into places that would resonate with the music but also mean something to fans.

Between us, we started to build a story outline that would feature Mountain Studios, where the song was recorded, and Montreux in Switzerland, which was not just the studios' location but also where Freddie lived at this particular time.

Unfortunately, Mountain Studios itself no longer exists, but the control room has been recreated as part of a Queen exhibition on the original site. A while ago, Jake pitched me the idea of creating 3D models, so we jumped at the chance to include that here. A whistle-stop filming day in Montreux would enable us to capture other significant landmarks, and so the concept for the video really started to take shape.

At this point, I took the idea to Brian and Roger. There was an outline for the story we wanted to tell and samples of the archive that would be featured, and I also sent them examples of how the 3D model might look.

What did Queen think of the idea?

Simon: Brian and Roger immediately bought into the concept, and we were on our way. They gave us complete freedom to realise the vision, and then we shared edits with them to get their input. Queen has a long and illustrious catalogue of iconic videos, and their judgement is always spot on. They were delighted with how the video was taking shape, and their feedback and suggestions at this stage proved invaluable and helped us finesse the final piece.

It was a truly collaborative process, and I hope the positivity of that experience comes across in the video. Although the lyrics can be interpreted as melancholy, Queen is always about togetherness and triumph, so we wanted the video to feel upbeat and empowering. I really hope that's what people take away when they see the finished product.

What were the biggest technical challenges in making the video?

Jake: A few elements of the video required more attention in pre-production. Getting the scale and proportion of the studio set was important, so I started by discussing this with Patrick McBride, the model-maker and set designer, ahead of time. We needed each set to be large enough to fit a camera in but intricate enough to retain detail and proportions with their live-action Mountain Studio counterparts.

Patrick had to improvise on the shape of the studio, as the only source material we could access was a single-angle still from the "Jazz" album artwork, where we see the studio filled with instruments through a wide-angle lens.

Queen has a long and illustrious catalogue of iconic videos, and their judgement is always spot on. They were delighted with how the video was taking shape, and their feedback and suggestions at this stage proved invaluable and helped us finesse the final piece.

On set, we loved the effect of a torch shining direct light through the triangular shapes of the roof, but when combined with a high frame rate and smoke machine, the footage suffered. Fortunately, we reviewed the footage in-camera fairly swiftly and overcame the issue by choosing a softer setting on the torch.

This gave us that ethereal aesthetic, almost like stage lights for a show's finale, which we allowed to play out for the entire outro sequence with a slow dolly out. Transitioning our control room shot with a live-action shot from Montreux was always going to be tricky, so I chose very carefully. If Patrick's model's proportions didn't match the locations, we could have easily bumped into more issues; fortunately, he'd designed them with such precision that they seamlessly transitioned. You can see the ink spill transition at 01:23.

The projector was displaying an edit I'd created ahead of time, but once we'd lit the scenes and introduced smoke to the equation, the projections were barely visible on the walls. As a workaround, I masked parts of the walls in post, layered the edit on top of the footage, brought the opacity down, and added blending modes to achieve a similar effect.

Ned Champain, DoP, brought the vision to life through his magical camera work. Where manual zooms would've presented challenges with tracking in AE, we shot static duplicates I could digitally scale in post. It's making decisions like that on set that disposed of issues in the edit. Foresight and a DoP who understands an editor's requirements: that's the formula!

What software and hardware did you use to create the video?

Jake: I used a combination of software from the Adobe Master Suite, with a key focus on Adobe After Effects (AE). Masking mixed-media elements was integral to this project, and I've always found AE's masking capabilities really intuitive and effective. With the more intricate masking, I worked within Photoshop and imported to AE.

I utilised plenty of blending modes, which allowed me to seamlessly layer archive footage onto the set, retaining the texture and details of the models. Whenever you see two videos playing beside one another, there's a slight delay in imitating the aesthetic of a stereoscope, which holds greater significance to those who follow Brian's work outside of the musical sphere.

There were many little VFX obstacles to overcome. For example, between 0:49 and 0:56, I had to create a shadow to fall across the framed clips on both the left and the right. Matching the tone, shape and pace of the existing shadows wasn't simple but was made achievable with shape and masking tools within AE.

Freddie's lyrics and signature at 2:41 were extracted from a page and animated using stroke and trim paths, allowing us to incorporate his actual cursive.

The lyric sheet for Face It Alone didn't exist in Freddie's writing, so Karolina Papp, assisting animator, dissected the letters we needed from a scanned letter from Freddie to MTV and rearranged them to create the lyrics. Karolina also did an exceptional job of animating the casino silhouette scene (2:04-2:22), where she isolated dancing clips of the band from Invisible Man rushes and, using alpha channels, filled the silhouettes with a flitting montage of Miracle-era archive footage.

What are the main lessons you learned from this experience?

Jake: It would have been useful to test the projector with the smoke and light elements ahead of time, perhaps allowing an additional prep day with the on-site crew to run thorough tests with the full setup. Once lighting rigs, frame rate alterations and smoke were introduced, it made a considerable difference to the visibility of the projections, which had taken time and patience to edit meticulously to the music.

The other lesson is less of a lesson and more of a realisation that's becoming clearer each time I create work I'm proud of... my contentment is rooted in creativity. Having the opportunity to explore personal creativity with a band as influential as Queen, with a producer as skilled and open as Simon, is more than I could have imagined for myself.

Simon: There is a well-known aspect of Queen's history of how the band resisted using synthesisers throughout the seventies – going as far as to write 'No Synthesisers' on their album covers. When they finally introduced them on their 1980 album, The Game, it was on the strict understanding that the technology would be used to enhance their instruments, not replace them. That's a lesson I take into every project I work on with Queen.

No matter how impressive the technological advancements are, anything we use must be in the spirit of enhancing the raw material. What lies at the heart of the piece, i.e. the song, is the most important element, and everything else revolves around that. Just because technology is available to do something doesn't necessarily mean we should. Fortunately, in Jake, I have a collaborator who totally gets that, and I hope between us, we got the balance right on this one.