How designer Luke Tonge is rewriting the rules on creative placements

The Birmingham designer's "anti-placement placement" is part bootcamp, part studio safari, part masterclass in confidence.

When a design student lands a placement, they typically know how it goes. Shadow someone, do a bit of work, make the tea, then leave. Luke Tonge, a Birmingham-based designer and co-founder of the Birmingham Design Festival, looked at that model and thought: 'I can do better'.

For the last four years, Luke has run what he calls a "anti-placement placement"; an annual two-week residency at The Jointworks, his coworking space in Birmingham. There's no client work, no free labour, no fetching coffee. Instead, there's a structured programme designed to give emerging creatives something far more valuable than a line on their CV: confidence, connections and a sense of where they might belong.

A bootcamp with heart

The format is deceptively simple. Each morning, the cohort gathers with Luke for an hour on a "big topic": a presentation followed by open conversation. Then come two further sessions. These might be visits to agencies, printers, fabrication studios or animation houses, or guests coming in: freelancers, writers, PR professionals, accountants, educators, makers.

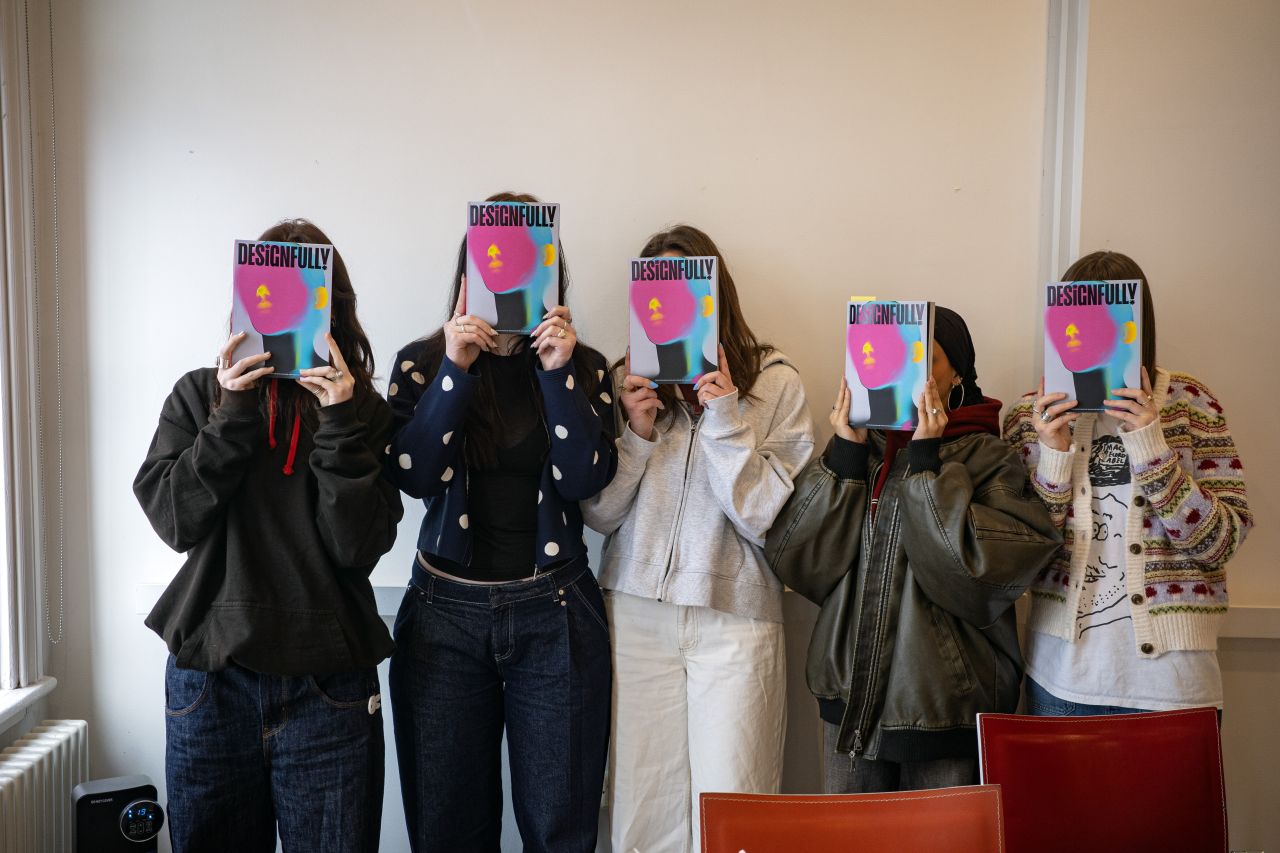

The only brief is a personal manifesto, presented at the end of the fortnight. The final days include portfolio reviews and presentations, recognising that communication and confidence matter as much in this industry as the work itself.

"It costs me a lot of money," notes Luke. "It doesn't pay me anything other than seeing them improve and succeed. But when I thought about what would actually be the best use of my time and resources, it was investing in people who really want to learn and watching them grow."

Broadening the definition of success

One of the programme's aims is to demystify the creative industry. For example, a design degree can unintentionally lead students to believe the only legitimate outcome is becoming a graphic designer. Luke wants to blow that open.

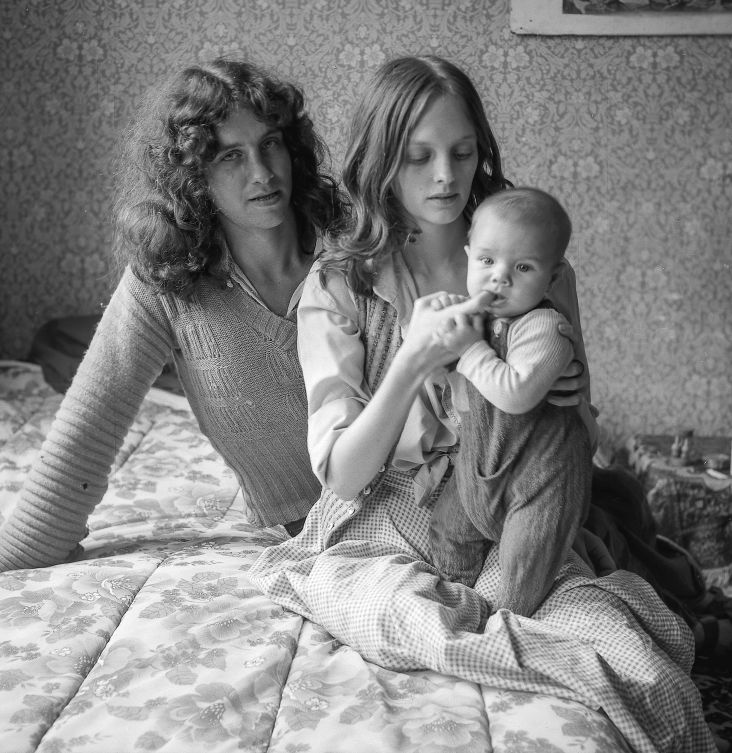

This year's cohort of eight—who happened to be all women this time, although not by design—met screen printers, leather makers, account directors, project managers, animators, writers, and PR professionals. Many had never even heard of some of these roles, let alone considered aiming for them.

"Graphic design graduates shouldn't see it as a failure if they don't end up as a graphic designer," stresses Luke. "It's a success that they've found what they're good at. But they'll only know that's an option if they meet people and see different paths."

Seeing results

The results are striking. One student met university friends just three days in, and the first thing they said was: 'What's changed? You seem different.'

"They don't have to wait 20 years to figure it out," Luke says. "I can see in them that they're capable of that confidence now. Sometimes they just need the right environment to realise it."

Unfortunately, the environment they've emerged from often pushes them in the opposite direction. You may be familiar with "cringe culture"; the tendency among young creatives to self-censor their enthusiasm for fear of seeming "too keen". Luke sees it as a genuine barrier to entry.

"The more bothered you seem, the more bothered I'm going to be about you," he counters. "If you're trying to play it cool and act like you don't really care, I'm not going to be that invested. Studios need enthusiasm. We need that young energy.

"If they're already censoring that energy for fear of coming across as cringe, then we're all going to seem really boring and bored all the time," he adds. "I'd much rather they lean into their weirdness, be sincere, be enthusiastic, and really care about things."

The real payoff

Ask Luke why he does it, and the answer is layered. Part of it is values: a belief in service and generosity. Part of it is self-awareness; he's explicit about the privilege of being a white man with a platform and connections, and credits his wife with helping him to see his "blind spots" when it comes to gender equality.

Another part of it is personal. "I was quite a shy student; I didn't always know how to navigate the industry," Luke recalls. "If I can shorten that journey for someone else and help them feel confident sooner, that feels worthwhile."

The programme earns him nothing financially. But he does not measure success that way. "I get 52 weeks in a year," he reasons. "I can give a couple of those away without it really impacting too much. I don't measure success by squeezing every second for money. If I can make enough to live and then give time away to help people, that feels like a better metric."

A model worth copying

The most important thing about the anti-placement placement is that it's not meant to be unique. Anyone with a network, some time and a willingness to be generous could do something similar.

"They've all left as best friends, and that's one of the best parts," smiles Luke. "You need supportive brothers and sisters in this industry. If they come away not just with contacts, but with a little network of people who've shared something intense together, that's powerful."

So for anyone reading this who's thought about what they could give back—a morning, an afternoon, a conversation—the message is clear. You do not need a coworking space in Birmingham to make a difference. You just need to be bothered.