Haçienda Landscapes: Ben Kelly on his retrospective of the iconic Manchester nightclub

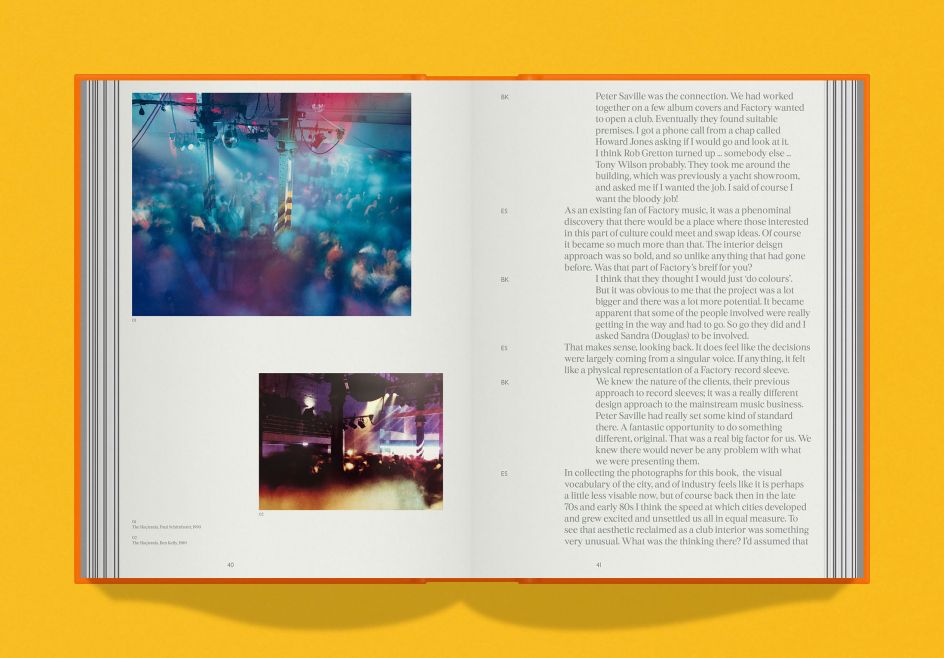

Even if you weren't around in Manchester during the 1980s and 1990s, you've probably heard of its iconic nightclub, The Haçienda. Launched in 1982 by Factory Records as an indie music venue, it went on to become the nerve centre for an explosive house and rave scene that reverberated globally.

Although it closed in 1997 and was demolished in 2002, there's still a special place in the heart of clubbers and music fans around the world today for The Haçienda. And so, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of its creation, the venue's original designer Ben Kelly and photographer Eugene Schlumberger have launched a Kickstarter campaign to fund a new book.

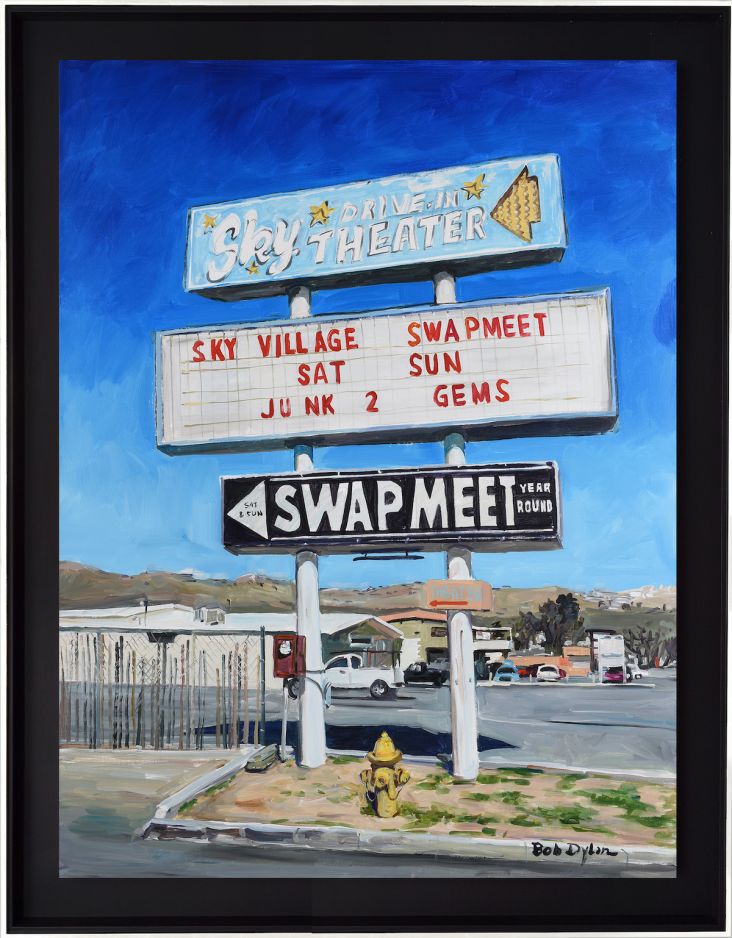

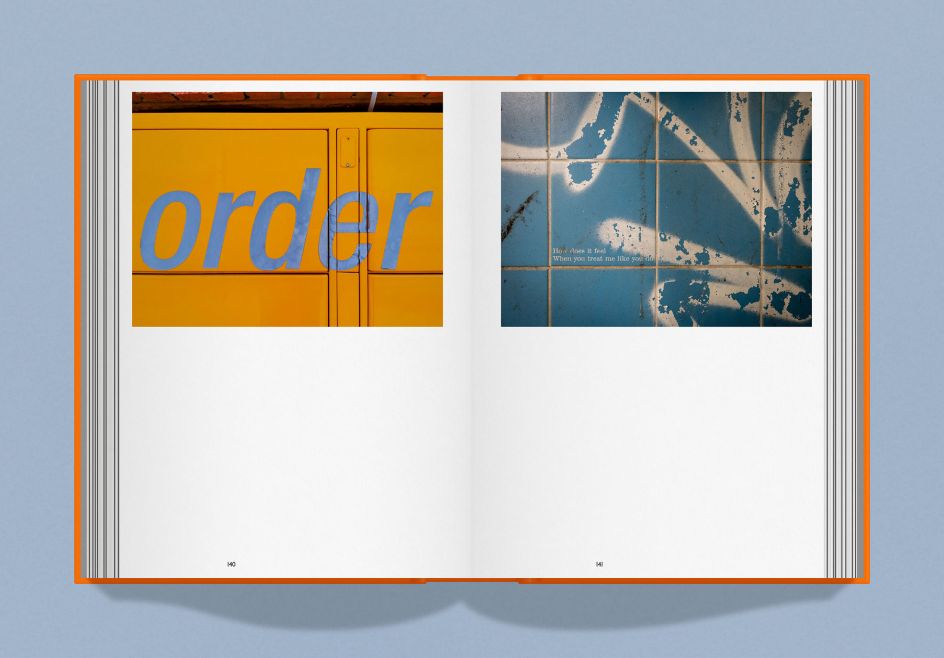

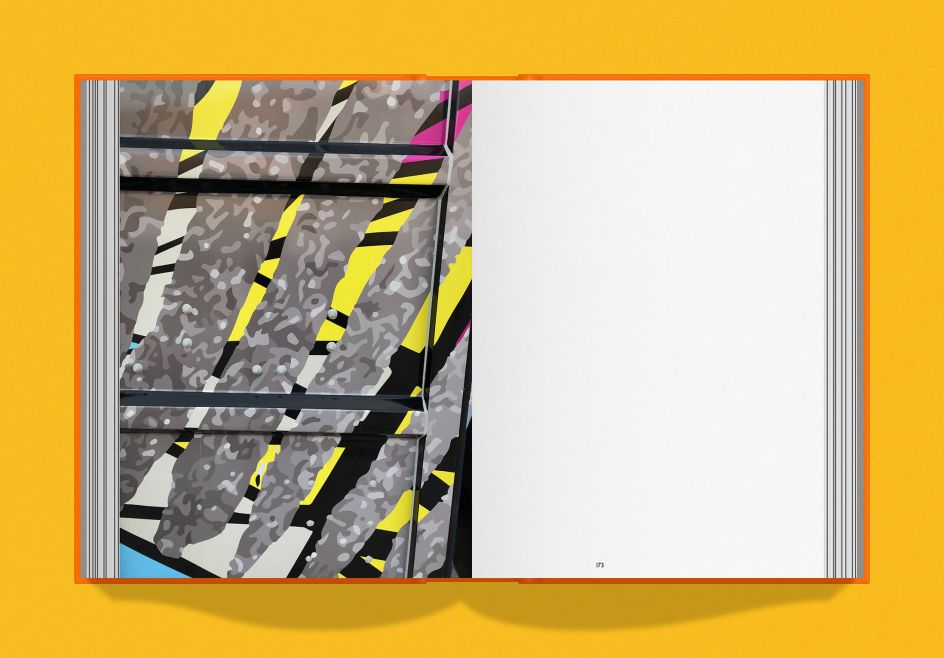

Part photobook, part visual history, Haçienda Landscapes reflects upon the club's enduring design aesthetic via photography of the industrial landscapes of the North, the graphic language of the everyday, and items selected from Kelly's own archives – much of which has never been published before.

The book can only be purchased as part of the Kickstarter campaign, which will only be funded if it reaches its goal by Thursday, 15 July. So if you're interested, head to the Kickstarter page while the going's good.

In the meantime, we spoke to Ben, who now heads up the interior design company Ben Kelly Design, about how he approached the design of the Haçienda, the club's enduring legacy, and the impetus behind his new book.

What was it like working with Factory Records in the early ‘80s?

As clients, they were very different to the sort of clients that I'd had experienced up to that point. They had an independent ethos, a spirit of doing it their way, and being totally separate from the major record companies. And the great thing was that once they'd asked you to do something, they'd let you get on with it. That's partly, I think, why such great work came out of it.

You worked with Peter Saville on a number of iconic Factory record sleeves. How did that come about?

For Joy Division's single Love Will Tear Us Apart, Peter based his sleeve artwork on what had previously been the cover of my thesis as a student at Royal College of Art. And that was a big, important thing that cemented our relationship.

We also worked on the first album cover for all Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark, which won all sorts of awards. That was really my first step into doing graphic design work. And I introduced the idea of perforating the sleeve, which was all about process. So Peter and I had this sort of symbiotic relationship. I was seeing what he was doing, and he was seeing what I was doing. So it was a pretty tight relationship.

Where did the idea for The Haçienda come from originally?

Joy Division became New Order, money started coming in, and the group went to America, went to the clubs in New York. Then they came back and said, 'We want one'. They had this kind of bullish attitude about opening a club. So I got a phone call one day, asking would I go up to Manchester to have a look at these premises, with a view to possibly designing a nightclub for Factory. The place was in a pretty poor state of disrepair. It was a mess; it was not in good shape.

I think they thought Peter would design it because he'd designed pretty much everything else they'd done or released. Peter looked at it, though, and said there's absolutely no way that he could do it. But he said, I know a man who can. That's where I came in. He thought of me partly because I'd designed one of the first fashion shops in Covent Garden on Long Acre, quite a big store.

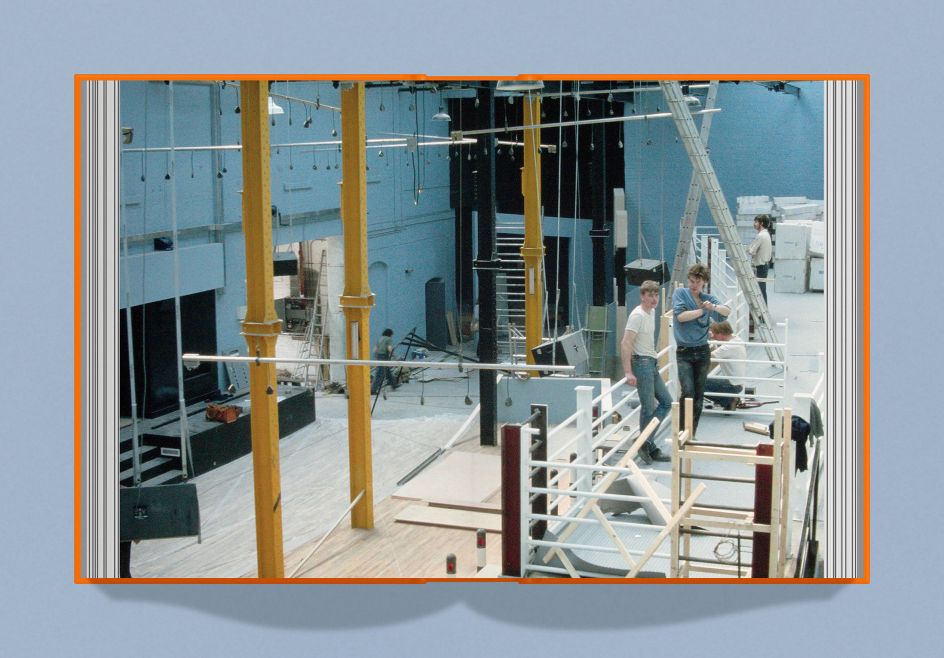

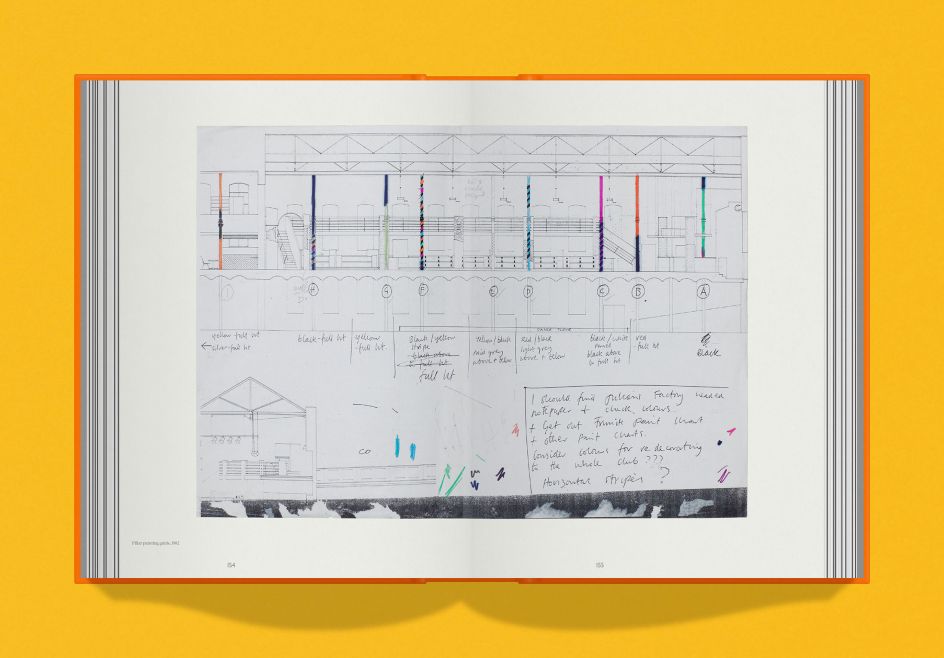

So I had the tour [of the Haçienda] with [Factory boss] Tony Wilson and a couple of other people. I could see immediately that it was a much bigger job than they thought. I think they thought maybe it was a lick of paint, you know, tidying it up a bit, putting a bar in, and away we go. But it was much, much more than that.

So, how did the design of The Haçienda develop?

If you use the word 'nightclub', that implies a certain kind of thing. But they also wanted bands to play in there. They wanted a bar. They wanted people to dance in there. So it was a hybrid. You know, is it a bird? Is it a plane? Is it a nightclub? Is it a disco? Is it a venue?

It was all of those things. And a lot more, because the potential was there for it to be flexible and change over time in terms of how it was used, how it was treated and how it was lit, depending on whether it was a band playing one night, and a dance night another evening.

Plus, of course, they put exhibitions on in there. At one point, there was a hairdressing salon in the basement. So many different things happened because of the scale of it, and I was determined that it should have that flexibility.

What were the biggest challenges along the way?

The brief grew and grew, and it was a kind of an organic process. But – and I've said this many times – the biggest debate was: where would the stage go? What was the orientation and location of the stage? And there was a big argument going on, I think, mostly between Tony Wilson and [New Order manager] Rob Gretton.

Rob wanted it at the far end. And I said it should be to one side. My view was that if the stage was at the far end, it would be a venue. The emphasis would be on bands playing on a stage. And it had the potential to be much more than that.

Ultimately, the argument was won that the stage should go on the side. So the bar was at the far end, the stage was to the right. And that led to all sorts of problems with sight-lines; the acoustics were awful.

But I'd just take a few steps back and say what I think was the great thing. The strength of the project was that the client – Factory/New Order – had never commissioned the design of a nightclub before. And I had never designed a nightclub before. So there was an awful lot of naivety. But I think that the strength lay in that naivety.

We weren't carrying baggage or preconceptions. And the Factory attitude meant that once they'd asked the designer to do something, they were free to get on with it. So I had that kind of freedom.

And as a result, you created something quite groundbreaking.

Nothing like it existed in the UK. What did exist were two extremes. You either had dive places in basements, with black and sticky carpets, and a bit of a spotlight; fairly rough and ready places. Or, at the other end of the spectrum, aspirational places like Stringfellows with flock wallpaper and chandeliers.

There were a few places around in Manchester that were slightly different to those two extremes, but certainly nothing like the Haçienda. So to me, the Haçienda was like a kind of three-dimensional version of what they'd done previously in two dimensions. It was a bit like making a big painting or a big piece of sculpture.

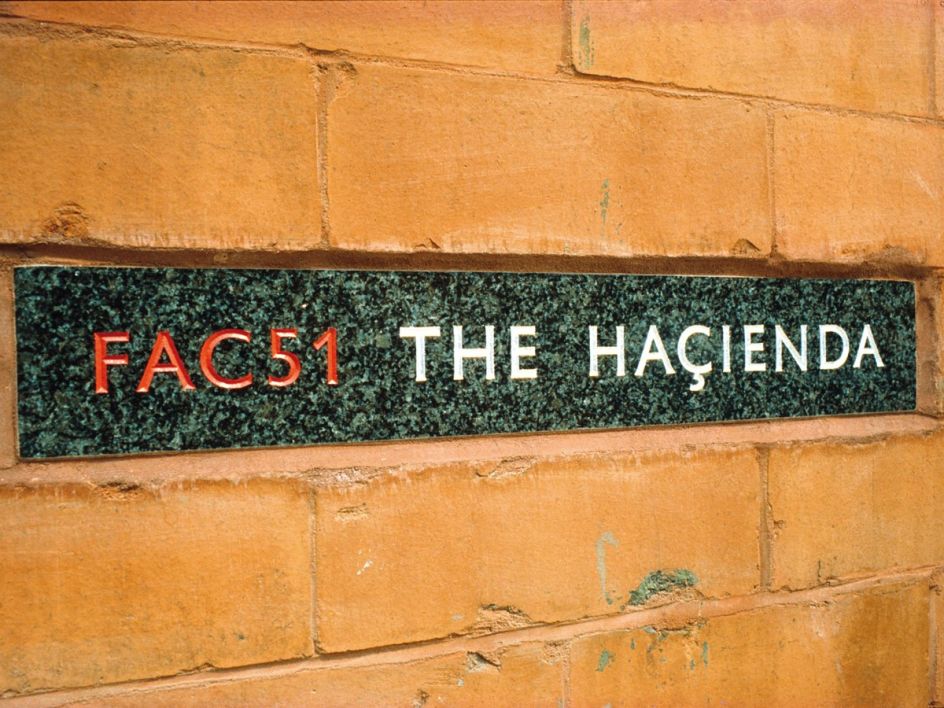

The only thing that announced its name to the street was a tiny little hand-lettered and carved granite plaque about 12 inches long, beautifully carved by a monumental stonemason with red enamel and Silverleaf set into the lettering. And I know people travelled from all over the world to visit it, and had trouble finding it. But that was part of the mystique. You know, you eventually found that little thing, which was quite beautifully done in the kind of spirit of the album covers, if you like.

And you went in and eventually came out into what I call a cathedral-like space. As Tony Wilson famously once said, "Every city needs its cathedral." So the Haçienda became Manchester's creative cathedral, I think.

I used to call it the monkey on my back because it never went away. It was all I ever got asked about. And it kind of pissed me off for a while. However, I realised that it was a privilege, and it's led on to many things that would never have happened otherwise.

But The Haçienda wasn't an instant success?

When it opened, after the first couple of nights, it stayed almost empty for quite a long period of time because people weren't used to it. They didn't really know what it was. I think they were probably scared. And it took a long time for it to find its feet and for people to understand. Eventually, though, they made it their own.

Now, it's been acknowledged that the Haçienda was the starting point of a new era for the city. It's been acknowledged by the City Council, by the RIBA, by everyone that it started the regeneration of Manchester.

Even though it's now closed, its legacy remains strong.

That's why it occurred to me to do a book. Because as I repeatedly say, the Haçienda never dies. There are still things happening around it, whether it's Haçienda Classical, whether it's exhibitions, whether just endless digital, so many things. And so, I've put a collection of things I've collected over the years that people have never seen into this book alongside my photographs and those of my co-creator Eugene Schlumberger.

I used to call it the monkey on my back because it never went away. It was all I ever got asked about. And it kind of pissed me off for a while. However, I realised that it was a privilege, and it's led on to many things that would never have happened otherwise.

There's a fondness for it. There are people all over the world for whom the Haçienda was one of the important times of their lives. Wherever I go, I meet people who say, "You designed the Haçienda? Bloody hell, I met my wife there, I met my partner there, I got the idea to start a business there, I had the best time of my life there, it changed me.” It did so many things to so many people.

Having said that, this book's not nostalgic at all. But it is something to hold, something that you can look at and feel; it's tactile. And in the spirit of Factory. Plus, it's a book, you know, it's not bloody digital! It's real. You can touch it; you can turn the pages. Beautiful. The way it should be.