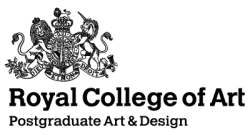

Courtesy of Makiko Harris. Photo by Ben Pipe

Applying for a master's is a big decision. When it means leaving a career you love, moving to a new country, or stepping into an institution where you're not sure you belong, it can feel like a scary leap into the dark. But for three recent graduates of the Royal College of Art—now award-winners and internationally exhibited artists—that leap turned out to be the making of them.

Lukman Ipese, Camila Barvo and Makiko Harris came from very different starting points. Lukman was a UK-based marketing manager balancing a postgrad diploma at UAL with a full-time job. Camila was working in textiles for a fashion brand in Colombia. Makiko was an established artist in California, hungry for something beyond her comfort zone.

What they had in common was a gut feeling that they were ready for more, and that the RCA was the place to find it.

Trusting your instincts

None of them took the decision lightly. Lukman is candid about his initial reservations. "I must admit I'd never had a desire to study at the RCA," he says. What changed his mind was listening to art director Giulia Garbin's guest lecture at UAL. "Witnessing first-hand the depth of knowledge she acquired during her master's at RCA and her creative growth left me envious," he recalls.

Courtesy of Lukman Ipese

Courtesy of Lukman Ipese. Photo by Icey You

Courtesy of Lukman Ipese. Photo by Icey You

Courtesy of Lukman Ipese

Courtesy of Lukman Ipese

Camila turned down the RCA the first time because she was offered a job in Cali, Colombia, with a fashion brand. But after 18 months, the issue wouldn't go away in her mind. "I remember thinking: when am I going to stop procrastinating and work for my own dreams?" she explains. "There was this gut feeling telling me to explore my creativity further within materiality. I felt London and a master's at the RCA seemed like the ideal place to allow myself to take the time and develop a creative voice."

For Makiko, meanwhile, the pull was the city itself. "Coming from San Francisco, I was hungry for the density and intensity of the London stage and its access to a more international art scene," she says. "It felt like the right moment to leave my comfort zone and immerse myself in an environment that would challenge what I thought possible."

Freedom to become something new

What struck all three was how much freedom the RCA gave them to rethink not just their work, but their entire creative identity.

"I entered the RCA thinking I was going to learn more embroidery techniques to evolve my textile design background," says Camila. "But that all changed when I started to challenge what embroidery meant to me, what gestures went into the action of this technique, and what that was revealing of myself. It was during that year at the RCA that I recognised myself as an artist. I left with a new way of approaching and understanding my work contextually."

Courtesy of Camila Barvo. Photo by Sarabande Foundation

Courtesy of Camila Barvo. Photo by Rene Lazovy

Courtesy of Camila Barvo.

Courtesy of Camila Barvo

Lukman's shift was just as profound, if different in kind. "Being completely honest, I didn't know what a practice was until the RCA," he admits. He'd expected the move from marketing into design to be mainly about building confidence and making stronger work. Instead, the RCA fundamentally changed what design meant to him.

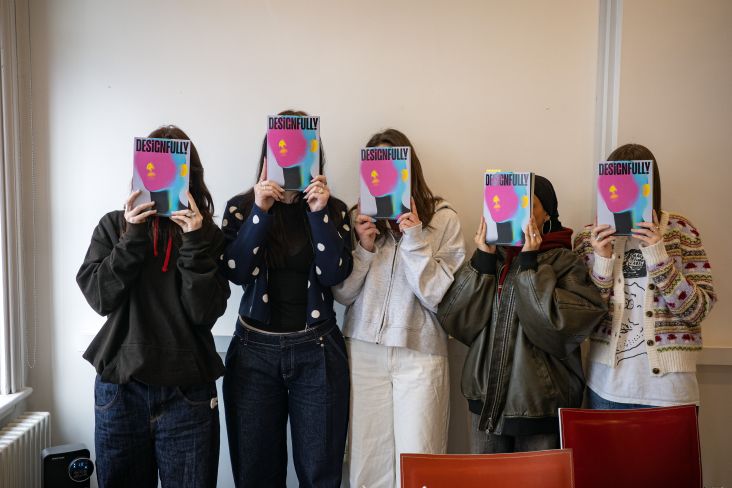

"A turning point was being introduced to participatory and collaborative methods," he says. A course called Making Worlds With Others, where students worked with Year 6 pupils on storytelling and confidence-building, was pivotal. "It reframed design for me as something relational and shared, rather than something produced in isolation."

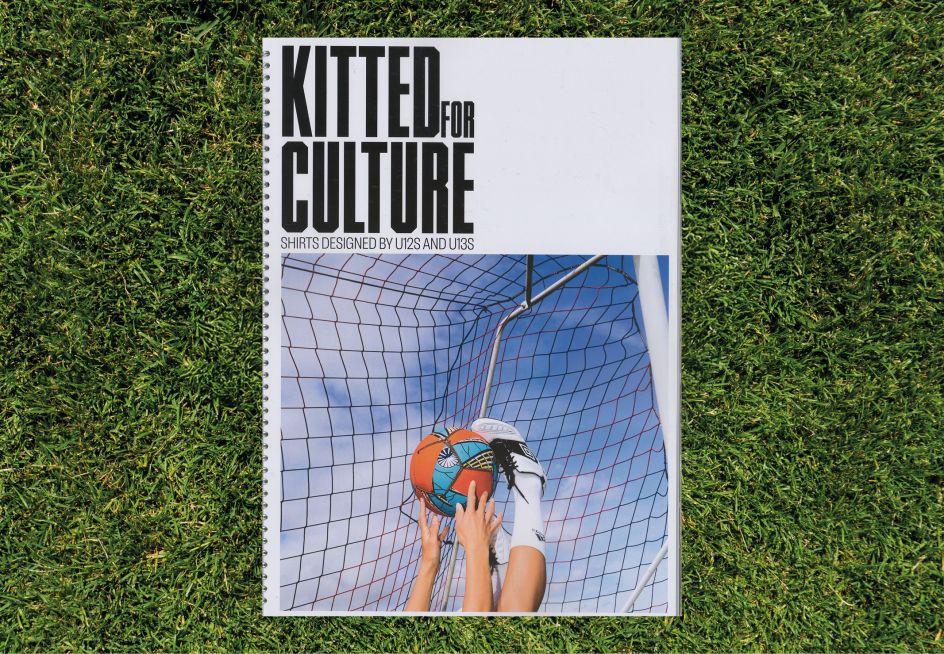

That new way of working fed directly into his final project, Kitted for Culture. Reimagining the football shirt as a cultural artefact, he reshaped how he saw his career. "I realised my marketing background wasn't something to leave behind but something to reframe, helping me communicate ideas, build partnerships and sustain projects," he notes.

Makiko describes a steep but ultimately liberating learning curve. "When I arrived in London, I didn't even know what Frieze was. Suddenly, I was surrounded by peers who seemed fluent in the language and logistics of the international art world. I battled serious imposter syndrome at first, but the environment forced me to learn fast, think on my feet, and ultimately believe I belonged."

The people who make it possible

Ask any of these creatives what made the biggest difference at RCA, and the answer isn't a building or a piece of equipment; it's the people.

Camila credits her tutor Celia Pym with fundamentally reshaping her approach. "This mentorship was very significant to me," she stresses. "Celia challenged and questioned me in order to push further the origins of my practice." One piece of advice has stayed with her above all: "Never stop making, because making will give you the answers."

For Lukman, it was his tutor Joseph Pochodzaj. "He pushed me to be critically aware of extraction, and to only work with communities I was genuinely part of or invited into," he explains. "That guidance helped me articulate Kitted for Culture as more than a series of football shirts, and to recognise it as a cultural and social project rooted in identity, representation and collaboration."

Makiko tells a similar story. "The technical staff are the heart and soul of the RCA," she says. "Above and beyond their roles, they became my collaborators, co-problem-solvers, and genuine supporters of the work. Several of these relationships have endured well beyond graduation; these technicians are still friends and advocates I turn to for advice."

Courtesy of Makiko Harris. Photo by Ben Pipe

Courtesy of Makiko Harris. Photo by Ben Pipe

Courtesy of Makiko Harris. Photo by BJ Deakin Photography

Courtesy of Makiko Harris. Photo by Ben Pipe

This principle underpins everything she does today. "My practice depends on collaboration with fabricators, artistic collaborators, technicians, gallery staff and curators," says Makiko. "The RCA taught me art-making isn't a solitary endeavour, even though it can oftentimes feel like one. It's built on trust, community and the generosity of others."

Should you take the leap?

Want to follow in these award-winning creatives' footsteps? Camila's advice is simple. "Don't stick too much to the label your degree gave you," she says. "Creativity can tap into any role or practice."

Lukman, meanwhile, urges prospective students to throw themselves into the full experience. "You get out what you put in," he says. "Work on projects you actually care about, learn from your peers, and let yourself enjoy it socially as well as creatively, as informal conversation can unexpectedly grow into something bigger." He also encourages applicants from non-traditional backgrounds to see their experience as an asset. "Don't see it as a disadvantage. My marketing skills became one of my biggest strengths; the power of a persuasive cold email led to some amazing donations."

Makiko adds that it's a big social, financial and emotional commitment, but that it's worth it. "If you come prepared, stay strategic, keep your eye on your personal prize and embrace the challenge, it can be transformative," she emphasises. "The key is knowing yourself well enough to navigate it on your own terms."

Three very different journeys, one shared conviction. The RCA didn't just develop their practice; it changed how they saw themselves.

Lukman Ipese studied MA Visual Communication. Camila Barvo studied an MA in Textiles. Makiko Harris studied an MA in Contemporary Art Practice. Camila was granted a residency at Sarabande Foundation and was shortlisted for the John Ruskin Prize. She also received the highly commended post-graduate award from the UK Textile Society in 2024. Makiko was selected for New Contemporaries (2026), is a finalist for the Cass Art Prize and was longlisted for the Women in Art Prize.