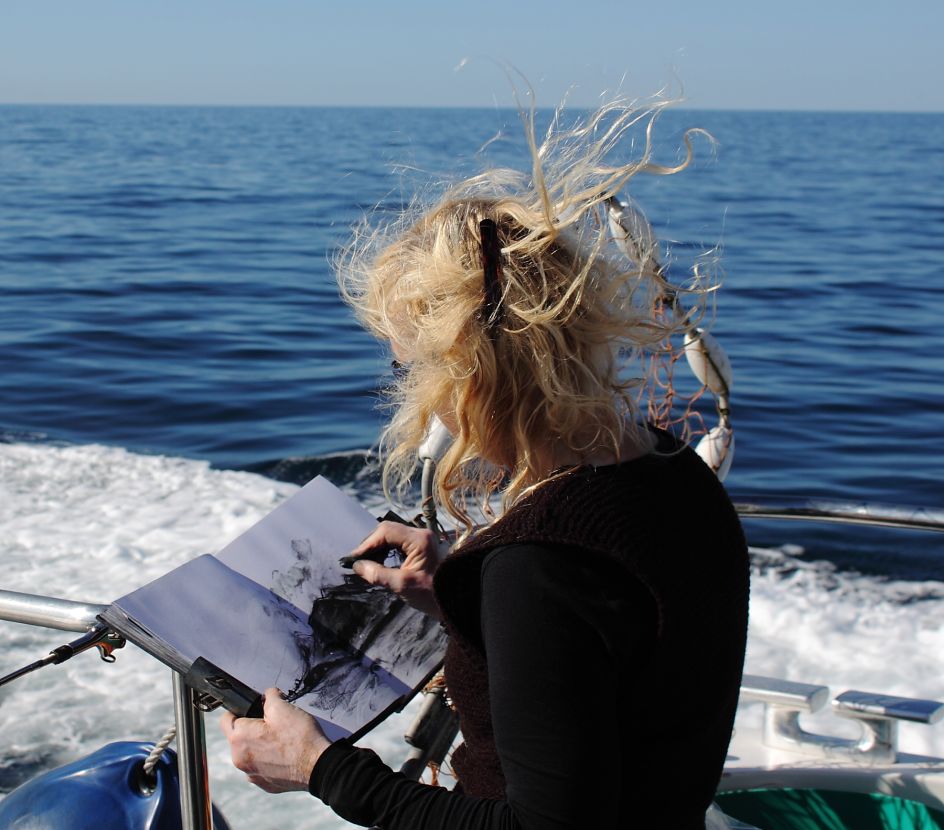

Janette Kerr on being a foul-weather artist, her passion for the sea and painting outside

Acclaimed seascape artist Janette Kerr has a thing for the northern landscape. Described as a foul-weather painter, she's renowned for spending weeks on board boats and ships to get up, close and personal with her favourite subject, no matter the weather.

For her latest work, she enjoyed three weeks on a three-masted schooner sailing up the coast of Svalbard in Norway up to the Arctic Circle. And, more recently, she was inspired by the Shetland Islands, where she, in fact, lives half the year.

Contemporary and experimental, Janette does not aim to create meticulous studies of the landscape, preferring instead to respond to what is sensed rather than what is seen. Her paintings explore the boundaries between representation and abstraction whilst embodying the power and immediacy of both land and sea. We spoke to Janette about this and more.

It's an obvious first question, but why the sea?

The house where I spent my childhood was three minutes from the sea. My parents had a B&B and my brother and I spent much of our time on the beach. I saw the ocean in all states, from calm peaceful sunny days to winter waves crashing on the sand.

I learnt to swim in the sea, to plunge and dive through large waves in rough weather, sometimes being swept off my feet, dragged by the suck of the current, rolling over and over in a tangle of foam and sand to arrive gasping on the shore.

Days spent floating on my back looking up at sky and clouds, feeling the tug of the gentle swell, scaring myself by swimming so far out that my feet couldn’t touch the bottom.

I remember family days out to the Dorset coast, places such as Winspit in Dorset, where, with my father, I would dive off rocks into deep water and look down into the depth below me. I’d watch my father swim so far away he’d become a tiny dot on the horizon, and worry he wouldn’t come back. Occasionally, a summer visitor would be swept out by strong currents, and rescued by lifeguards who’d tow the floundering figure to safety, breathing life back into them.

There were trips in boats and I’d feel the sea moving beneath the boards, and imagine what might be down there.

Now and then a storm would come in, so strong that breakwaters and beach huts would be destroyed, and I’d go down to watch vast waves thundering in, foam flying high, and hear the suck and roar of the ocean. These were the best times when there were few people around and I’d have the sea to myself. I guess this is why the sea.

You're described as a "foul weather artist". Have there been any moments when you really have had to down tools?

I was once invited to join a pilot boat travelling from Sullom Voe oil terminal on Shetland going to rendezvous with a tanker from India. The weather was pretty rough, so we had to wait in the sea while the tanker came to us.

Consequently, our boat was rolling wildly while I was drawing big waves breaking around us, with the horizon appearing and disappearing. I had to stop while I was sick in a bucket that the men casually passed to me; I recovered and went on with my drawing.

Another time, I travelled out on a small ferry to the Out Skerries and the weather became pretty wild – a force 8. I insisted on staying out on the deck to draw; waves were washing over the deck and we were pitching about and I was just hanging on. Everything became so wet I gave up trying to drawing and just watched the sea, so I guess it was a kind of down tools, but I was still out there, storing it all away for when I got back to the studio.

More recently, I was drawing on Shetland in very windy weather and had packed up and was feeling really pleased with one of the drawings I had just made. Turning round to take a photo, my rucksack suddenly took off and was swept off the cliff into the sea below. It was far too dangerous to attempt to get it back. So that was the end of my drawing trip that day. The sea had claimed not only all my tools but my drawings of it as well.

Do you find you talk about the weather a lot?

Absolutely! I’m always checking where the wind is coming from and which way the clouds are moving. I need to know where to go to find the big waves, a bit like surfers do, only the waves I want aren’t the same – they like those big waves that roll in evenly, while I like crazy seas that are unpredictable.

I don’t mind rain or hail or snow. Mist is good, although there are limits! On Shetland, the weather changes so fast that I need to know what’s coming in, and if it’s a sunny, still day – well, I can go to the studio and work. I listen to weather forecasts (although for Shetland they’re not always right), I watch the sky and I start to know what’s coming. You can see the dark clouds bringing rain travelling across the sea, the fog rolling across the surface of the water.

So you prefer to work outdoors, either by the shoreline or on a boat. Is that important to your process?

Working outside is essential. Walking and making drawings and paintings in the landscape is a way of having a kind of conversation; a way of fixing the moment and experience of ‘being there’. Crouching with my sketchbook and painting on rocks by the sea, or in snow painting with freezing fingers, being blown across hills by gusts of wind, drenched by spray and sleet, and going home with salt-encrusted hair and skin – it’s all part of how I work.

Drawing on a boat in the midst of a heaving sea and surrounded by a living mass of water, the world tips, the horizon disappearing and reappearing, fear and exhilaration experienced simultaneously.

I look at what’s below me, stare out across the water, think about stuff completely unrelated to my environment, feel spray hitting me, waves pushing the boat around; there’s this physical immersion in the landscape, a resonance between an internalised world and an external one.

It all gets inside your head and spills out onto the page; they are intuitive responses – active engagements with the landscape. So being outdoors is integral to my working process.

The attempt to put down what is ‘out there’ – a vast fluid dynamic environment – shifting with every turn of my head and passing cloud, on a small intimate piece of paper, seems pretty mad – doomed to failure.

I felt this particularly when I was in the Arctic confronted with an immense glacier and an even more immense landscape of ice and snow and mist and mountain. The drawings I make are not accurate topographical depictions, but more about reflecting movement through time – what is sensed, I can’t say even understood. Not sure what this all says about me!

This is what fuels my large paintings. I try to take all this back to the studio and recreate these experiences when I’m working on large canvases. When I look at some of the small drawings made outside I can remember where I was and what was happening, even what I was thinking.

Whilst out and about, what tools and comforts do you have in your backpack?

I try to be really organised. I've learned from those occasions when I’ve forgotten some essential item. My now pretty dirty rucksack is usually full of tubes of oil paints and rags, bits of board to work on and mix paint, a larger one to work on, various sizes of brushes, palette knives, bulldog clips, masking tape, bottles of turpentine, containers that I fill from the sea or streams and puddles, a sketchbook.

I take charcoal, chalk, graphite, spray, maybe some watercolour, sometimes an apple and a sandwich if I get round to making one, and an Eccles cake or two. I’ve taken to bringing a small roll mat, as it gets quite cold sometimes when I’m sitting or crouching on the ground.

That’s probably it – I always wear waterproof trousers and jacket, hat, and thermal layers, oh and fingerless gloves (very important!). And a flask of coffee back in the car is very welcome on my return.

You're quite hands-on aren't you? Is it true you also speak to locals and fishermen to gain insights to help with your work? Any stories you care to share?

I’ve spent time talking to all kinds of people about the sea – fishermen, story-tellers, oceanographers, archivists… people who know far more than I can ever hope to know.

I’m not a sailor, don’t know one rope from another, but talking to those who really know the sea is really useful; hearing stories about the modder dye, which is a way of reading the surface of the sea and knowing where land is even in a heavy stumba (sea fog), tales of fishermen sleeping under the sheet for nights when they're out fishing 40-50 miles off the coast.

Learning about the use of meids to aid navigation – a way of being able to work out where you are by lining up local landmarks. I’ve spent some time with oceanographers who showed me oceanographic diagrams and algebraic formulae describing the surface of the sea and waves (I sometimes write these into my paintings), and talk to me about how the sea feels the bottom of the ocean and responds, and the fetch of a wave – how far waves can travel before the break.

They don’t really know what causes freak, extreme waves to occur. There are lots of oral recording of stories in the Shetland Archives about terrible storms and loss of life and incredible feats of navigation. The 1881 Gloup disaster on Yell, remembered as ‘The Bad Morning’, is one example. Unaware of an impending storm heading down from Iceland with hurricane-force winds, crews set out for fishing grounds forty miles offshore.

Of those that left, 10 boats failed to return. Fifty-eight men lost their lives. The disaster left thirty-four widows and eighty-five orphans, so you can imagine how it affected the community. These accounts humble me; make me aware of how the sea must be treated with respect, and not to take chances because it’s dangerous for even those who are experienced sailors.

Why are the more turbulent seas a running theme in your work?

It’s what excites me. Quiet, flat seas with sunny days just don’t interest me. I’m a Romantic painter – I like the ‘sturm und drang’ (storm and drive). I don’t paint in a quiet, calm way, I paint and draw in a confused charged sort of way, constantly changing things, so I suppose this reflects the turbulence – and it reflects how I am.

You've worked in the Arctic Circle. Can you tell us more about that experience?

The Arctic was a very full-on experience. The expedition started from 78°13.7´N, 015°36.3´E at Longyearbyen, Svalbard, travelling north on the Antigua, a Barquentine tall ship. Where we went was to some extent dependent on weather, particularly wind direction and strength.

We were a multi-national group of artists, a couple of anthropologists, a scientist and the crew, living together on board the ship for two and a half weeks (no mean feat in itself!).

Most days we were either en-route somewhere, or moored up to land at sites in front of glaciers, standing on beaches confronting walrus, trekking up mountains to the top of glaciers, and making work.

Sometimes we found ourselves in uncharted waters; sobering since this was because of retreating glacial ice – the impact of global warming.

The furthest north we sailed was 79°43,7´N, 011°00.5´E, landing on Smeerenburg (Blubber Island), a small island where the Dutch whaling fleet worked in the 17th-century, and where there is still evidence of the ovens used to boil down whale blubber.

Arctic history is a legacy of desires, a stage for personal quests and heroism. Before I went to the High Arctic, I spent the year reading accounts of expeditions – voyages in search of riches or routes through to riches, attempts to reach the Pole, failed expeditions to find the northwest passage, all for personal gain, prowess, for national pride, for mankind.

So the Arctic has a complicated history of exploitation; indigenous persecutions, controversies over Inuit land rights, and exploitation of natural resources. It has been fished, animals hunted to virtual extinction, mined and claimed. The land was stolen, people destroyed by disease, and, of course, there’s today's global warming issue and ecological destruction.

This is the ‘pristine’ Arctic I was in. Trying to grapple with all this information, as well as experience first-hand the sheer scale of this environment, it was challenging trying to make work.

Sometimes the landscape seemed to just draw itself – it looked unreal. I made some experimental ephemeral pieces – freezing watercolour and letting it melt and flow over the paper – and this will feed into future work.

Some of the things I tried didn’t come off; my attempt at kite-flying with a camera didn’t work as it was either too windy or there was no wind or it was raining or snowing or there were walruses or the kite strings stuck to the permafrost.

The impact of the landscape was certainly immersive. Standing in front of a vast glacier – before I went I had no idea how they would look – that they are so vast and so blue, so pitted with ridges.

There was silence, but also the occasional thunderous sound of glaciers calving, of ice bumping and scraping along the side of the boat, the crack of ancient air escaping from ice. How do you convey all that in a moment on a piece of paper?

I remember the frustration of trying to draw a series of peaks with the mist moving over them – to get something down on the paper – what is ‘out there’ in this a vast fluid dynamic environment, shifting with every turn of my head and passing cloud, on a small intimate piece of paper – seems mad, doomed to fail.

There’s only so many marks that can be made, only so much rain or snow that can fall, before the surface deteriorates, the drawing disappears. In my notes, I wrote, ‘I can’t put down what I’m seeing, it seems quite insane to be trying’.

What is it about the Northern hemisphere that fascinates you so much?

I’ve worked with the northern landscape for the last 15 or so years; have always been drawn to its extremes and edges.

I like cold places; they make you alert, such extremes take you to the essentials of living and survival. For the last nine years, I’ve worked 60º North in Shetland, where the weather changes so rapidly. I’ve travelled by sea up the northern coast of Norway, but I’d never been so far north as when I went to the Arctic.

Travelling this far north feels like traversing the extent of human occupation – the outer limits of the human world. If we measure the world by our own experience of it, the far north is not of this world, not like other places. It’s beyond human experience.

In the words of the poet of the north, Henry Beissel, ‘The North is where all the parallels converge to open out’. The idea of a limitless, almost incomprehensible, metaphysical space encourages us to think of north as moving always out of reach, leading to a further north, to an elsewhere that we never reach.

Is there anywhere you've not yet been that you'd really love to paint?

Loads of places – mostly cold! I’d like to spend more time travelling at sea out of sight of land. The Northwest Passage is somewhere I’ve read a lot about and that would be an inspiring trip.

And then I’d like to go and paint in the opposite end of the world – the Antarctic. On the Endurance, the ship Shackleton took on his famous early 20th-century Trans-Antarctic expedition, the second engineer of the crew was Alexander Kerr, and I am sure he was a relative, so maybe it’s in my blood to want to go to such extreme places.

The description of their battles with sea and ice is overwhelming. Also, I’d like to travel to Iceland and Greenland. More cold places. But I’m also interested in going to find and draw beside volcanoes.

Do you ever have days when you can't quite capture the sea as you'd like? How do you get over this?

I have endless days in the studio when I’m working on a painting and can’t get it right and despair of ever painting a good painting again. I’m not good to live with on these occasions!

I get over it by working and working at it and going back to my plein-air drawings – putting myself back to the sea. There’s always a struggle at some point to find the overall coherence in each painting. Eventually, a sense of direction will emerge and then I know it’s finished.

What's the best thing about your career?

I can do what I want when I want – most of the time. And people seem to respond to my work and buy it, which is a real bonus as it helps fund my projects and travels.

What's surprised or delighted you lately?

Someone recently came into the gallery and cried in front of one of my paintings because she said it reminded her of being at sea – she is a long haul sailor. I felt honoured that I had managed to capture something that was so important to her.

Any advice to aspiring artists out there?

You won’t get anywhere by sitting around waiting to be found. You have to get out there – work out what it is you do best and push yourself. Take chances, don’t say no. And if you get rejected allow yourself a day to be fed up and cross... and then get back to work.