Open Square Collective's installation for the London Biennale combines aesthetic appeal with activism

Malta's first-ever contribution to the London Biennale is a playful labyrinth that viewers can interact with. We chat with its creators about the research and concept behind it.

From war and sanctions to the rise of populist and nationalist movements, it seems like we're moving from a globally connected world to an increasingly parochial one based more on regional blocks than true internationalism. So it's heartening that this year's London Biennale is swimming against the tide, with its theme on 'The Global Game: Remapping Collaborations'.

For 2023, the global exhibition and thought-leadership event invites participants to imagine and enact new forms of international cooperation and participation, including with each other, through the medium of design.

There's nothing more global, of course, than our natural environment. So it's suitable that Malta is represented at this year's event by Open Square Collective, a design team strongly driven by ecological concerns and an urgent need for sustainable design and respect towards the world.

The collective, which includes fashion designer Luke Azzopardi, artist and academic Trevor Borg and architects Matthew Joseph Casha and Alessia Deguara, will present a large-scale installation called Urban Fabric at the Malta Pavilion this June. It's the first time Malta will be represented at the event.

Context and concept

Informed by contextual research and a deep-rooted appreciation of the need for sustainable design, the project re-contextualises the traditional Maltese village core. It merges two separate elements: traditional city planning and the Phoenician-Maltese tradition of fabric production and dyeing.

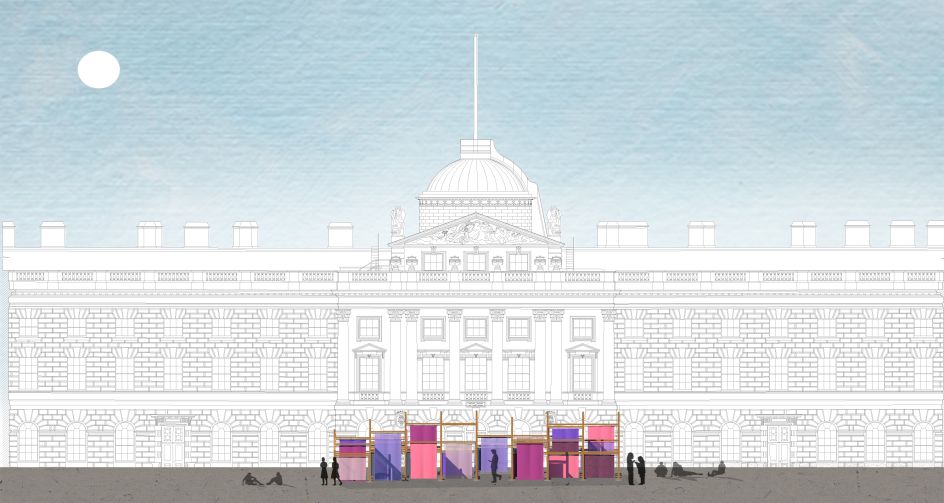

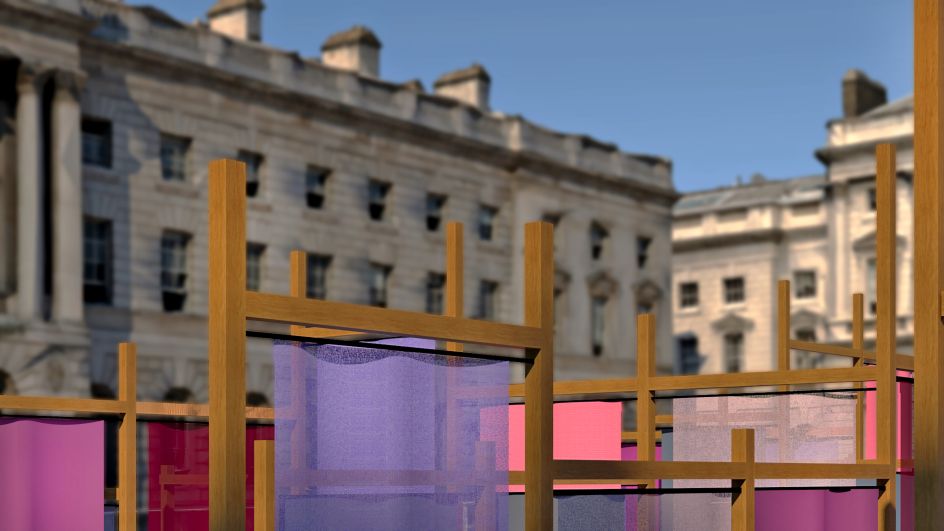

The installation creates a playful labyrinth derived from the original layout of ancient Maltese villages. The interplay of shadow and light cast by the installation as the sun moves throughout the day creates a dynamic experience in constant flux, fluctuating according to weather conditions.

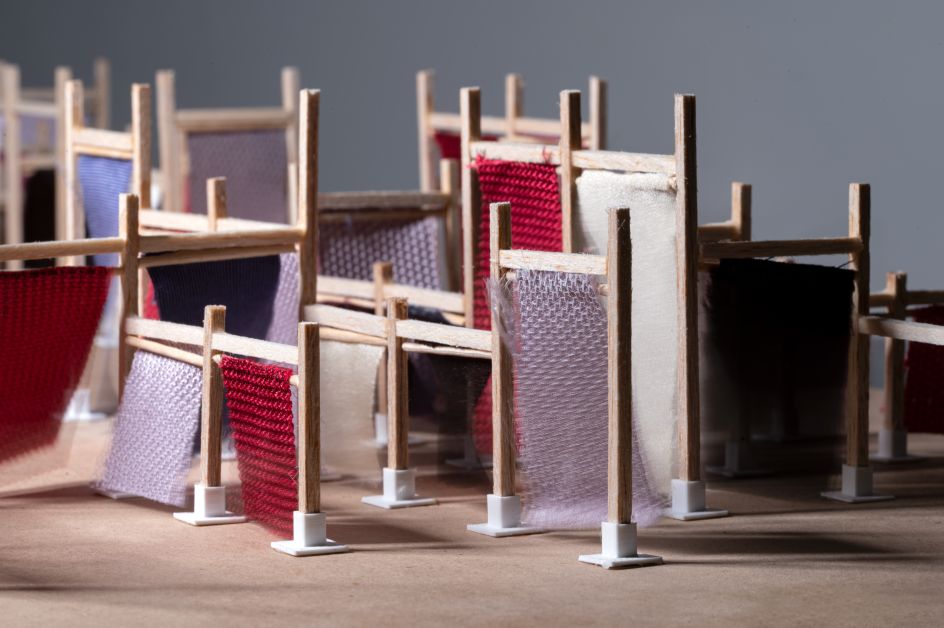

Urban Fabric uses wood, stone and organic fabric that is sustainable and certified eco-friendly as its main components. These components create a 'street-like' layout that enables the viewer to interact directly with the installation.

"The installation juxtaposes the past with the present since it brings together the ancient Phoenician tradition of purple fabric dyes, which was an important trade across the Mediterranean circuit, with the Maltese village spatial design," explains Trevor Borg. "Visitors will be able to make their way through history and architecture, traversing hypothetical streets and alleys leading to the central piazza. The installation is located in an ecocritical context as it draws on sustainable contemporary design aspects to comment on the stale nature-culture dichotomy."

The original concept stemmed from research by the team into the Phoenicians, experiencing the fine fabrics and artefacts of the time and using this experience as a foundation.

Specifically, the installation draws on source material documenting how the Phoenicians used to dye wool and linen garments, mainly using two types of Murex sea-snail species common along the Mediterranean shores.

"The first lap of this journey started at the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta, namely from the Phoenician section," explains Trevor, a senior lecturer and head of the Department of Digital Arts. "The rich purple tints acquired from the murex shell opened up various creative opportunities for us, and we found ourselves embarking on a journey through time. The rich purple dyes and the methods of working with fabric skillfully mastered by the Phoenicians influenced the beginnings of our project. They kept moving us, like the sails of a magnificent galleon, into so many different directions, which converged into one project: Urban Fabric."

Luke Azzopardi adds a further historical context. "Although the Trunculus Phoenicia Tyrian purple dye is entirely natural, bio-sourced and biodegradable, and can be left untreated, it can only be collected by diving and hand-searching for them on rocky coastlines," he explains. "The special sexual organ gland containing the valuable dye was removed, dried and crushed for further use, and this is what makes it still the most expensive fabric dye on the planet.

"There are whole accounts on how just outside Phoenician city calls, there would be mounts of thousands of murex shells out of which the purple dye would have been extracted," he adds. "We later found out that this happened outside of the city walls as the stench emitted from these molluscs and shells was extremely potent. We also found a recipe by Pliny the Elder, who had tried to recreate the Phoenician dye. However, it only survives in fragments and is largely incomplete.

"For reasons pertaining to ecology and marine biodiversity preservation, we opted for a plant/vegetable derived alternative dye in a similar shade of purple for our installation, which was paired with eco-friendly fabrics acquired in special lengths from various European firms."

The Open Square Collective, from left: Alessia Deguara, Luke Azzopardi, Matthew Joseph Casha, Trevor Borg, and Ramona Depares.

The project was also influenced by traditional Maltese city planning, says Alessia Deguara. "Historically, the Maltese village is built around the 'pjazza' (village square), which was the place where one would find all amenities in one place, making it the most accessible and social space in the village," she explains. "For Urban Fabric, The Maltese village core is re-contextualised in Somerset House, having the installation following a Maltese village layout, and seeing the centre of the installation become alive, just like the Maltese pjazza."

What about its construction? "The structure which holds the fabric and makes up the street-like layout is primarily made up of wood, which is sustainably sourced from local suppliers in the UK," says Matthew Joseph Casha. "We have decided to keep the structure as raw as possible in order to highlight the kind of workmanship involved in building the structure as well as keeping it true to its material origins.

"For the choice of fabric, we decided to work with linens, cotton and recycled polyester, which are all eco-friendly certified. The life of the materials involved in the installation will not end at the London Design Biennale, but will be re-used and upcycled in other future projects."

As for the overall message behind the project, Luke says: "The installation created by Urban Fabric Collective is one that draws upon visuals and stories from home: Malta. It is meant to instil in the minds of audience members the sense of the quasi-claustrophobic Maltese village. This is merged with a sense of spiritual sensibility as audiences walk alongside giant fabric drops of intense Tyrian purple shades. It is meant to be both awe-inspiring while striking terror in those who choose to get lost in it, both visually as well as metaphorically."

To learn more, visit the Urban Fabric website at urbanfabricmalta.com.

for Creative Boom](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/06/063686a9a3b095b9b1f0e95df917ed4bd342be1b_732.jpg)

using <a href="https://www.ohnotype.co/fonts/obviously" target="_blank">Obviously</a> by Oh No Type Co., Art Director, Brand & Creative—Spotify](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/6e/6ed31eddc26fa563f213fc76d6993dab9231ffe4_732.jpg)

by Tüpokompanii](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/58/58684538770fb5b428dc1882f7a732f153500153_732.jpg)