Priya Khanchandani on following your heart, the changing face of media and the lack of diversity in design

Priya Khanchandani is the editor of design and architecture magazine ICON. She has published dozens of articles for publications ranging from The Sunday Times to Bloomsbury's Encyclopedia of Design and spoken at numerous festivals, conferences and on BBC Radio 4.

Photography by Carl Russ-Mohl

Trained at Cambridge University and the Royal College of Art, she went on to work at the Victoria and Albert Museum on the acquisition of new objects and then as Head of Arts Programmes for India at the British Council.

Priya curated the India Pavilion, State of Indigo, at London Design Biennale 2018 and co-curated an exhibition about pattern for Lisbon Architecture Triennale 2019. In 2014, she and a group of colleagues came together to form the influential pro-diversity collective Museum Detox. Priya is also on the steering committee for Design Can, a campaign and online tool calling for the design industry to be inclusive. We chatted to Priya about her career so far and the things she's most passionate about.

Can you tell us more about your journey?

I haven't had a linear route into becoming a magazine editor. I think my career is proof that you don't have to have a set path. I studied Modern Languages at Cambridge, and I did a law conversion course and practised law for the first five years of my career. But I always wanted to return to further study and so decided to go to the Royal College of Art where I studied the history of design. That was in 2011, and basically, I haven't looked back since. I joined ICON as deputy and became editor within a matter of weeks.

So what was your upbringing like? Were you encouraged by your parents to go down quite a traditional route?

In an Indian immigrant family such as mine, the aspiration was always to be a professional. Definitely during the '80s and '90s when I grew up in Luton, which is where my grandfather ended up emigrating to when he came here from India in the 1950s.

My grandfather was the first person in our family, who was literate. He managed to get into university, studying medicine in Bombay, which was amazing. And then my dad also ended up becoming a doctor. So I think, yeah, the aspiration was from my grandfather that I would become a doctor, too, because I did well at school. But I was more interested in arts subjects. So I felt like doing law was the acceptable version within the cultural sphere, because I could study humanities.

I was always passionate about the arts. At school, I took up music lessons from a young age. I did clarinet, piano. I practised ballet. Different types of dance. Those things were always my passion.

It sounds like you made quite a compromise. You obviously wanted to honour everything that your parents and your grandparents have been through. You tried that other route but realised you needed to follow your heart?

Yeah, I think when I did my university degree, I did what I was passionate about because it involved languages, literature and visual art. I also did modern European cinema. It was an incredible liberal arts degree. But I think that was when I faced a dilemma. At that time it was the financial boom, so all the corporates would come in and do these career fairs. All my friends wanted to work in the City and they offered them high salaries upon graduation, even before they had finished their degree.

I did an internship at a law firm and they offered me a training contract when I was like, what, about 20 years old? I hadn't even graduated yet, which was kind of an incredible offer. They paid me to get through postgrad law school and guaranteed me a job at the end. Obviously, you had to go through a recruitment process, and it was competitive, but those opportunities were there.

I guess I always knew deep down that I wanted to work in the cultural sector. But you need financial resources to be able to do that. Living and studying in London isn't easy from that perspective, so it wasn't until I was able to support myself and was older and more aware of what I wanted that I decided to do what I love.

Even if I failed, I thought it was important to try at least to do the things that matter to me.

And you've not regretted it?

I think I'm lucky to have been able to make that shift. It was early enough in my career that law hadn't come to define me. I'd also learnt quite a lot of professional skills from working in a law firm and working hard, advising quite high-profile clients like Prada. And I could transfer those skills to the world I now work in.

Today, I travel the world to meet interesting architects, designers, thinkers and makers. See new museums launch like the new Bauhaus museum in Weimar and attend events like the Milan Triennale and Sharjah Architecture Triennale. I have the luxury of being able to see and talk about the things that interest me. It's a rich career, but it's not an easy path initially.

For young people entering these professions, like writing or curating, there isn't a steady stream of jobs. It's challenging and not necessarily for everybody. But I wouldn't change what I do. I've seen what you've done with Creative Boom, so I bet you love it, too?

Yes, I feel fortunate, but it's not been easy. You'll have seen the impact of digital on your career, too. So much has changed since we graduated – both good and bad?

The face of media has completely transformed. I suppose I've always seen my career as being more about design and architecture and then applying it across different mediums. That's not always been through the media. I've curated exhibitions for the V&A, worked in museums, and I've done a lot of public speaking. I also write for publications in different media.

I've devoted myself to running a magazine over the last couple of years. It's completely different from when I first interned at a newspaper 20 years ago. There's an increasing demand for fast news these days. Still, I think sometimes we have to try and step back and consider what's important in the world and what we want to read and consume, rather than being pre-occupied with the number of hits, which is increasingly becoming the sole barometer of success.

Absolutely. Chasing clicks and likes.

Since I joined ICON, I have probably spent the majority of my time on the print magazine because it's been monthly. That's quite a short turnaround for such a small team. But I have been working on evolving the brand to adopt a more multi-platform approach. That means more live events, growing our digital team, devoting more time and energy to online and social media. And we're going quarterly in print, so our magazine is going to be double in length but published just four times a year instead of twelve to allow us the flexibility to grow other media.

That's sad to hear, but you sound positive about it?

I think it's good because in a digital age we look to print to be something a little more special. The beauty of it is that long-form in print is even more acceptable because you get your news content online. It gives us a reason to make the magazine even more special, as an object and in terms of its content, and release it slightly less often. It can be more in-depth, with more focused pieces. We can also include more visual content. So yeah, we're gradually becoming a more "360-degree" type brand.

Are you going to do a podcast?

If we did that, we'd have to do it full force. We have experimented with it but have focused more on video, creating a one-on-one interview series as part of our ICON Minds platform. We've done interviews with exciting designers and architects like Camille Walala and Amin Taha.

The other thing to change both our careers was the global economic recession. We've had to diversify and find multiple income streams. Do you think there's such a thing as a job for life anymore?

Many of my colleagues at my previous law firm and the V&A are still there. But I think the space of innovation in the 21st century is not necessarily these types of institutions. I'm not saying I wouldn't work at one or that interesting things aren't happening there; they are. But I think that unlike in previous decades, since that recession innovation has been happening in other silos, too, and it's quicker to take root.

More people are doing freelance work, people forming their own collectives. And people are coming together in smaller organisations – that was partly why I wanted to work at a smaller enterprise like ICON, where I could have autonomy and more ability to be creative. I've also been able to bring in more diverse voices. I'm not sure I could've shifted that narrative as quickly at a larger institution.

ICON has traditionally reflected the makeup of design and architecture writing, which frankly hasn't been very diverse. As the editor, I've had the autonomy to try and change that; although I know there's still a lot of work to be done.

I think places of innovation are changing. That is partly down to the global crisis, as institutions have had to cut costs. But there is less opportunity, too. It's easy to evangelise the freelance life and people not staying in one job but actually, I commission a lot of writers, and I have freelanced myself, and it's not always easy.

Freelancing is often romanticised. But for many, people have had no choice but to work for themselves.

Exactly. It's a tough time for creative people, but that doesn't mean they can't be innovative. Creativity always finds a voice; the space for it just shifts.

You mentioned diversity. You're part of the campaign, Design Can. Why did you want to be involved?

I want to drive forward Design Can because the design world is a place that's accessible to the privileged few and it's about time that changed. When I once asked a magazine editor why he didn't commission more diverse design writers, including women, he said: but where are they? Design Can will hopefully help us rebut the "but". It will show that people of all backgrounds have something valid to say; they are underrepresented because they aren't in the right networks.

Working with Zetteler on setting up Design Can has enabled this message to spread and also helped promote some lesser-known designers from all sorts of backgrounds via our online resource page.

How do you think diversity in the design industry can be improved?

The design world can be significantly improved by celebrating – and representing – the rich diversity that exists in the real world. We need to see people of all backgrounds authoring design books, curating design weeks and standing at the helm of design institutions.

Recently, a young writer of colour told me she felt she would have had more opportunities in her career had her name been Harriet, and it made me feel so disillusioned; she deserves so much better. Working in our silos to help things change isn't ideal, and often involves preaching to the converted, but it is a step in the right direction. We had to do something to push the mainstream to catch up.

Why is an inclusive approach important to the success of the design industry?

Design can't thrive without an inclusive approach. The designer Victor Papenek once wrote, "The only important thing about design is how it relates to people." Design is supposed to empower people, and it can't fulfil that purpose without doing justice to the burden of representation.

Have you seen any positive changes since launching Design Can?

It is still early days for Design Can since we only launched six months ago. But having seen the changes we accomplished with Museum Detox over the past six years, I am hopeful that starting a conversation will give more visibility to the issues at stake. We have already had an overwhelmingly positive response from all corners of the industry – one editor even emailed me without being prompted to open up a discussion about how to diversify his brand. It was a real breakthrough moment, as up until then, I had only had such conversations with other people of colour.

Change is starting to happen. These are difficult conversations to have, right?

It's tough. But I think we're in a moment when it's becoming comfortable to have these conversations about diversity. It's almost becoming fashionable. Which is positive in one sense, but we need to make sure we stay real about it – that it's not just a fad which doesn't have any genuine traction.

We need the same breakthrough when it comes to disability. I recently went through a significant illness which is classed as a form of disability. I have found that much more challenging to talk about professionally than being a woman or a woman of colour; which is interesting because being a cancer survivor has posed me more challenges in my work than anything else. Illness is a huge taboo. It's not socially acceptable to talk about illness. We need to have a Me Too moment when it comes to health and disability.

How can we make these stories more visible?

As a woman of colour and someone who's gone through a major illness, I am acutely aware that everybody has a story. And part of the point of Design Can is allowing people with all sorts of stories to be represented – all the content on the website is crowdsourced, so people submitting people and projects is important. Not everyone is a privileged white man, and yet our industry is predominantly controlled by people from that homogenous background. We've just got to do better, for the sake of the generations that will follow us, to show them that as a society, we have the right values.

If music, fashion and dance can start to change, we can change, too. If we don't, we'll only reveal the shallowness of our values. And history will make that transparent.

To find out more ICON magazine, visit iconeye.com. And for more information on Design Can, go to design-can.com.

for Creative Boom](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/06/063686a9a3b095b9b1f0e95df917ed4bd342be1b_732.jpg)

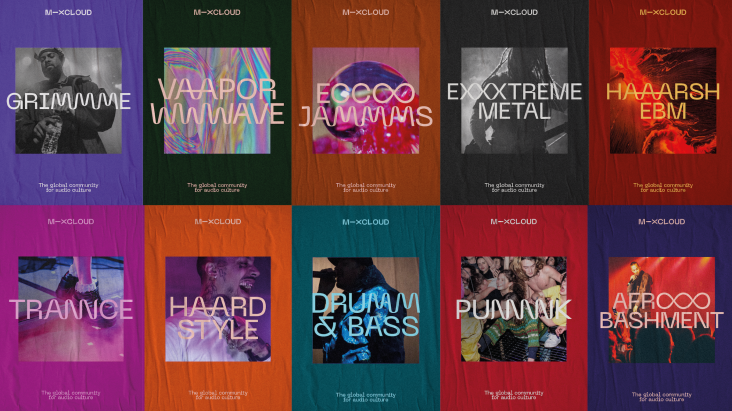

using <a href="https://www.ohnotype.co/fonts/obviously" target="_blank">Obviously</a> by Oh No Type Co., Art Director, Brand & Creative—Spotify](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/6e/6ed31eddc26fa563f213fc76d6993dab9231ffe4_732.jpg)

by Tüpokompanii](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/58/58684538770fb5b428dc1882f7a732f153500153_732.jpg)

from the book House Music published by [Dewi Lewis Publishing](https://www.dewilewis.com/products/house-music)](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/ca/caa0717758e6c7f9701cdd969bb215eb63e41ddc_732.jpg)