Is Adobe becoming the frenemy of creatives?

Adobe has long been the friend of creatives. But the rise of generative AI is putting it in a difficult position.

© Adobe

This week, Adobe is marking 20 years of its Adobe Max conference, and boy, does it have a lot to celebrate. For any software company to get thousands of people around the world watching them announce their latest features online is an impressive feat.

Luring others to pay thousands to attend in person is even crazier. It's a reflection of just how deep-rooted the company behind Photoshop, Illustrator, Premiere Pro and a dozen other tools is in the creative professions today.

Despite there being a number of good cheap or free alternatives, Adobe's Creative Cloud apps remain virtually unchallenged within most relevant sectors.

If you're a photographer or image editor, you need to know Photoshop and Lightroom. An artist, Illustrator. A motion designer, After Effects. Work in publishing? InDesign. Filmmaking's one exception, but even here, Adobe's making strong inroads, with chairman Shantanu Narayen happily pointing out in his opening keynote that Oscar triumph Everything Everywhere All at Once was made using Premiere Pro.

So everything is good, right? Well, it depends on where you're standing.

Keeping creatives happy

The benefit of market dominance for Adobe is clear: it can charge eye-wateringly high prices for its subscriptions, and creatives generally have to swallow the cost.

That's fine if your employer is paying, of course – yet it bites into freelancers' income quite substantially. So you'd assume that Adobe would be keen to keep creatives as happy as humanly possible.

And for the last decade, every time Adobe Max's rolled around, that's very much felt like the case. Each year, the company has used the occasion to launch an exciting array of AI-fuelled features that make using its tools faster and easier than ever. (See our 2022 roundup for examples). The mantra has been, "We're making the boring bits of your work easier so you can concentrate on being creative".

© Adobe

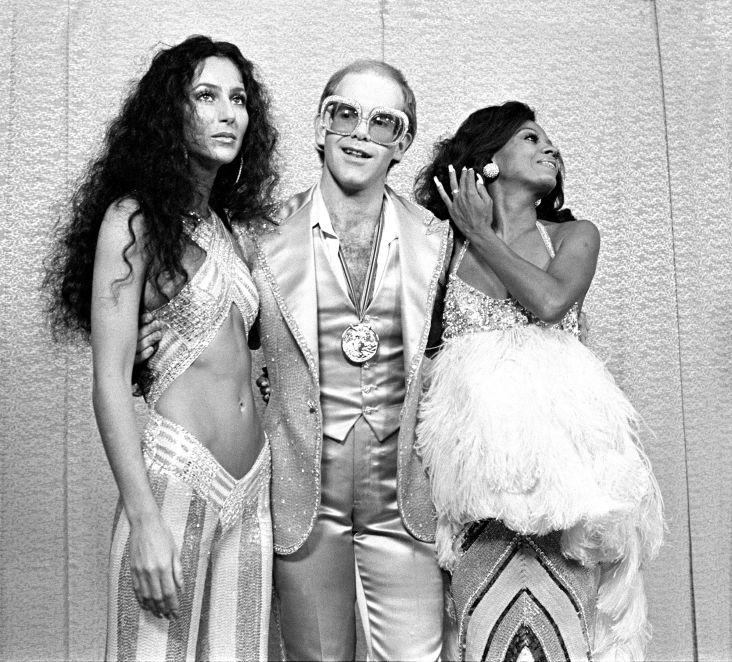

To be fair, this has been brilliant for a lot of creative pros. Removing an object from an image in Photoshop, for example, used to involve hours of tedious fiddling around and can now be achieved at the press of a button.

But this year, things felt a little different. Because video editing news aside, almost all the big announcements this year were about generative AI.

For the uninitiated, that means the ability to create entire artworks through text prompts alone. So there's less of a focus on helping creatives, instead delivering something that could ultimately replace them.

Nervous energy

Perhaps it was just me, but it seemed like this changed the energy in the auditorium from previous years. The key moment for me was when Adobe's president of digital media, David Wadhwani, announced excitedly that Adobe had served "three billion AI generative images" and waited for applause. Instead, the room fell silent. "Please clap," he begged. And there lies Adobe's dilemma in a nutshell.

Lol, @adobe just had a Jeb “please clap” moment announcing 3 billion AI generative images to date. @adobemax #AdobeMAX

— Dieline (@TheDieline) October 10, 2023

Yes, Adobe is trying to be the good guy by only training its AI on stock contributors who agree to have their work studied and copied. And that ticks one of the boxes of things creatives are angry about in protecting people's intellectual property. (In theory, at least. The way generative AI works is so obtuse that even the people in charge might not understand it, so it's difficult to give cast-iron guarantees).

But ultimately, it side-steps the main issue. Which is that generative AI is going to put a lot of artists out of business.

Money-saving offer

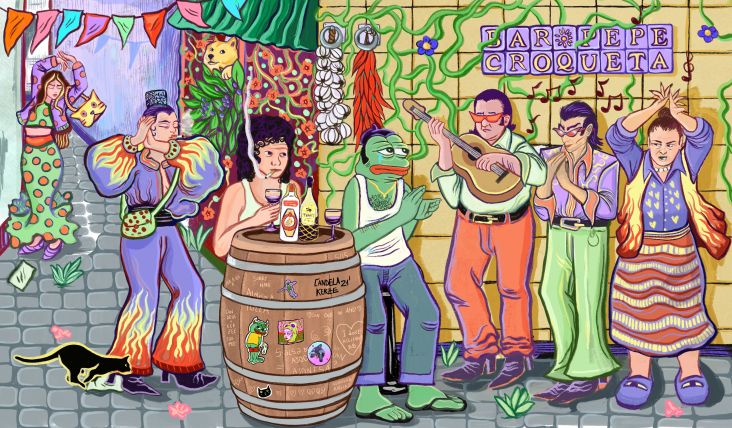

To take a recent example, this promotional poster for a new Loki series suggests that even giant global brands like Disney might be thinking: "WTF, let's give generative AI a try".

Disney too cheap to pay an artist to do their Loki promotional art, so we get this ugly AI shit again pic.twitter.com/47kWERGkhZ

— Mike Maynard (@SkullPirateMike) October 3, 2023,

Yes, Disney is denying this artwork was generated using AI. But even if we give them the benefit of the doubt, bear in mind that the recent settlement of the Hollywood writers' strike and the expected resolution of the actors' strike is going to raise the streaming giants' costs at a time when the cost of living crisis makes customers resistant to further subscription price rises. So promotional material will be one of the few areas where they might claw back a little cash to right the balance sheets.

And so, while there's no suggestion that Adobe's Firefly was used for this or any movie poster, it's possible that it eventually will. And we're not just talking about the entertainment business, of course, but the entire economy, which isn't exactly flush with cash either.

All this means that anyone who thinks generative AI won't cost jobs is kidding themselves. And that means Adobe is going to have a big PR problem on its hands.

What would you do?

To be fair, though, what alternative does Adobe have? Plenty of other tech giants are piling billions into AI, and if Adobe buries its head in the sand, whom will that benefit? Instead, Adobe seems to be pursuing the line, "This stuff is going to happen anyway, so let's try to limit the damage to creatives as much as possible".

Take photography, for example. Whatever AI Adobe throws at Photoshop, it's barely touching the sides when it comes to new tech that's coming to a phone camera near you.

For instance, the 'Magic Eraser' in the new Google Pixel 8 Pro allows you to remove objects from your photo and add new (i.e. fake) elements using generative AI in your phone. There's no need to transfer your image to your laptop and fiddle about with it in Photoshop at all. And the next generation of phones will inevitably push these ideas even further.

For example, imagine that before you even take a picture of your family, you select a mode that automatically turns anyone frowning into a face that's smiling. That would offer a lot of potential benefits for parents who want nice shots of their children. But it also presents danger in a world of fake news, populist movements and would-be dictators. Imagine, for example, seeing a photo of a politician smiling smugly as they view a scene of death and horror in Ukraine, Israel or Gaza.

Yes, ever since the birth of photography, it's always been possible to fake photos. But there used to be at least a bit of effort involved, and such technology was only available to a few select people. Making it easy for billions to take and share fake photos (and, in the near future, probably videos) is a bit like what happened ten years ago, when the emergence of social media made it easy for people to share unfiltered opinions, incorrect information and, well, bare-faced lies in text form. And look how that turned out.

© Adobe

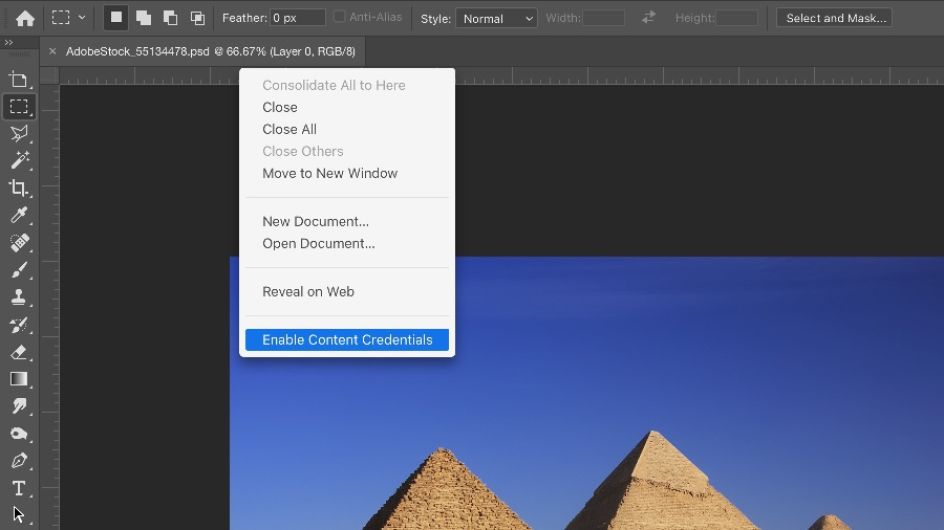

In this light, Adobe – who in the past were often cast as the 'bad guys' and blamed for all instances of Photoshop fakery – appear suddenly like useful people to have in our corner. Because if we're to live in a world where we can't believe the evidence of our own eyes, at least we need to have some sort of paper trail.

So imagine if, every time you saw a photo or video you're unsure about, you could simply click on it and get reliable info on how and when it was captured and what edits had been made. That's exactly what Adobe's Content Credentials scheme is aimed at, and useful extensions to this were among the announcements at Adobe Max yesterday.

Where do we go from here?

So where does this place Adobe in terms of its relations with creatives? Is it our friend, enemy, or something in between – a frenemy, if you will?

Ultimately, that will depend on how far down the rabbit hole the world goes with generative AI. Maybe it won't get any better than it is, and we'll all soon tire of looking at weird, uncanny valley figures with six fingers. Or maybe the tech will advance beyond our wildest dreams, and the terrifying world of Black Mirror episode 'Joan is Awful' will become something closer to reality.

Whatever happens, Adobe will have a tough job trying to navigate this brave new world without screwing over the people who made them what they are today. It's not a job I envy, I can tell you.

Or perhaps I'm just being paranoid: after all, I lived through a period when digital technology decimated what was once known as the record industry, and my own profession of journalism has not been short of challenges since the move to digital, either.

Meanwhile, if you want to come to your own conclusions, you can watch the entire Adobe keynote below and access other information about Adobe Max here.

](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/b2/b2766633bc2fe360d0c3ab5571804bf1ff257e5d_732.jpg)