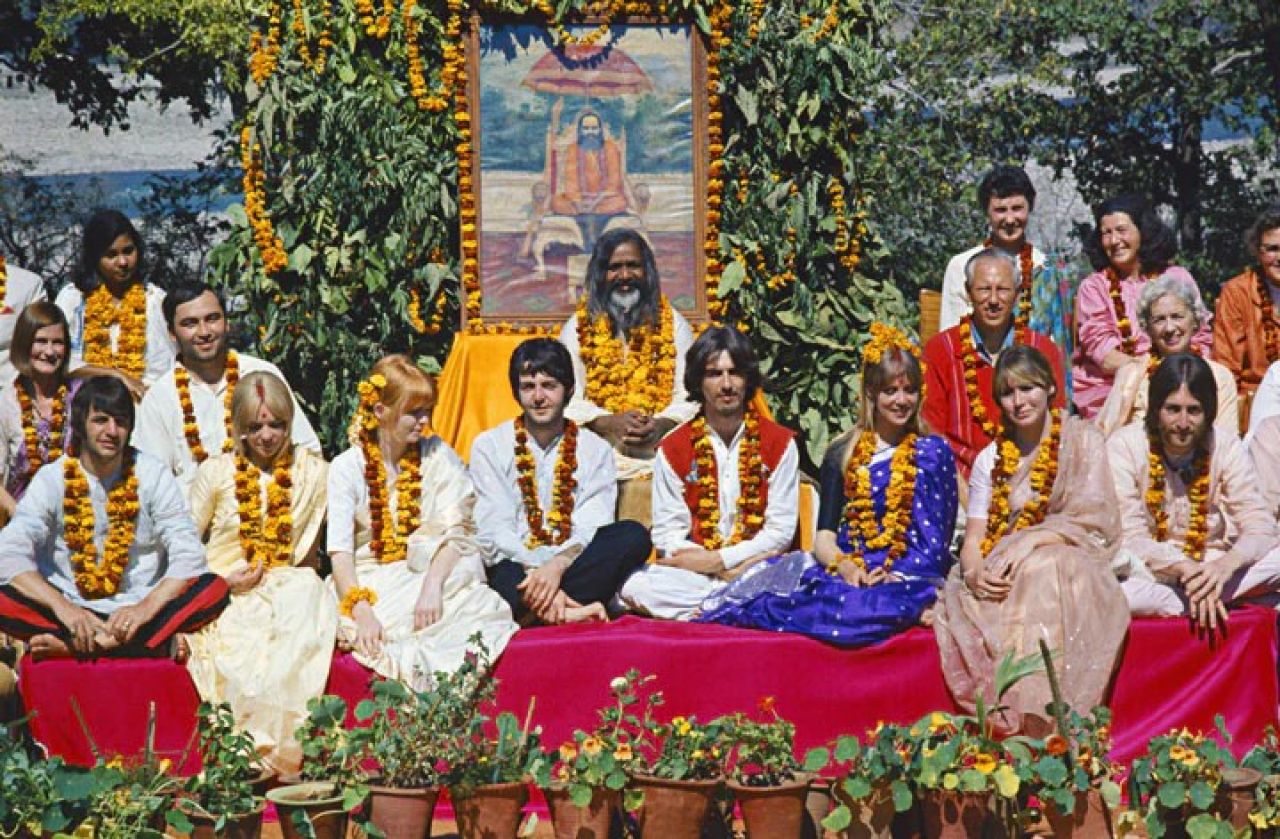

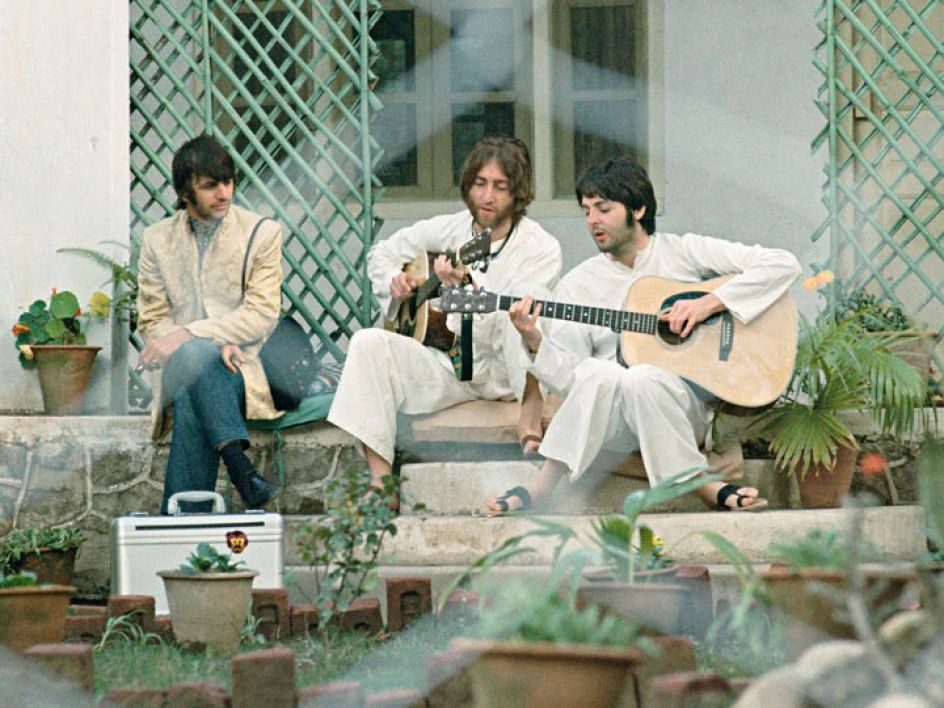

© Paul Saltzman. All Rights Reserved. One of the iconic photos Paul Saltzman took of The Beatles in Rishikesh, India

In 1968, aged 23, Canadian Paul Saltzman travelled to India with a cheap Pentax camera and no idea how to use it. He'd never studied photography. He couldn't work out exposures. His only guide was the folded instruction sheet inside a box of Kodak film showing little sun symbols next to f-stops.

Yet the pictures he took that February—of John, Paul, George and Ringo, whom he'd unexpectedly encountered at Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's ashram in Rishikesh—are now considered some of the most iconic shots of The Beatles ever taken.

Having since made 343 films and won two Emmy Awards, the president of Sunrise Films Limited, Toronto has plenty to teach creatives today… but it's probably not what you think.

Finding your purpose

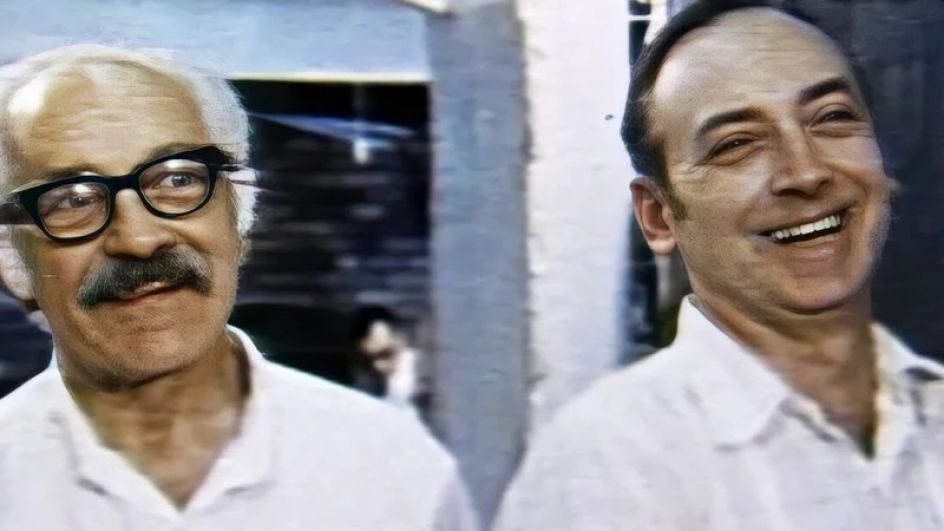

Paul discovered what drives him in the most unexpected way. In the early 1970s, he made a documentary about the Perlmutar bakery in Toronto's Kensington Market, a place of joy where five siblings joked with customers and the whole neighbourhood gathered. It took him two years to convince them to let him film there.

The Perlmutar Story won Best Documentary, Best Director and Best of Festival at the Canadian Film Awards that year, beating all the dramas. Standing on the pavement afterwards, a CBC interviewer asked him why he made the films he made. "I'd never thought of that," Paul recalls today. "So I took a breath and said without thinking: 'I make films about people who give me courage, to pass that courage along to others.'"

The Bakery documents the Perlmutar family's bakery at the heart of Kensington Market in Toronto, Canada

That moment of clarity led to another realisation: "I realised that I could spend my life making junk food for people's psyches, or I could make health food for their psyches," he recalls. "And it's irresponsible of me to make junk food for people's psyches."

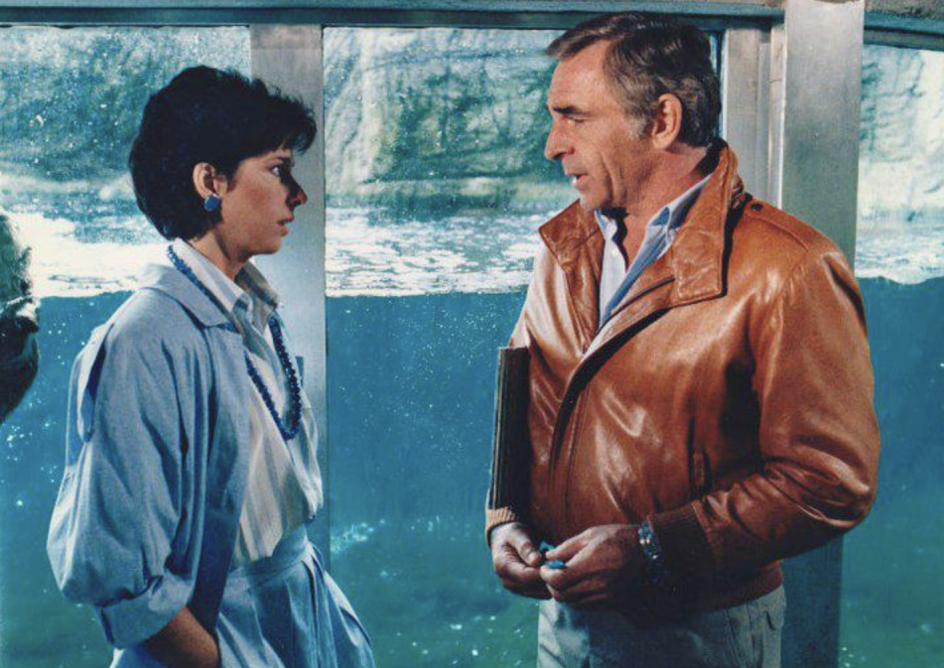

This principle shaped everything that followed. When he co-created the television series Danger Bay (1984-1990), for example, it was because he wanted his five-year-old daughter to be able to watch TV safely.

The action-adventure drama, set in Vancouver's oceans and mountains, ran for six years and 123 episodes, and was shown around the world. Every episode embodied good human values without being preachy. The series' bible stipulated that the hero would never resort to violence to intimidate or control. "A five-year-old could watch it, and they weren't learning the lesson that you use guns to control people," Paul explains.

123 episodes of Danger Bay were filmed between 1984 and 1990

The lesson? You don't have to compromise your values to succeed. Danger Bay proved you could make commercially successful work with complete integrity.

When the work finds you

Some of Paul's most powerful work has come from following his own curiosity. In 2007, he returned to Mississippi, where he'd volunteered for civil rights work in the 1960s with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, helping black people to vote in an incredibly hostile and racist environment.

It was a personal trip, and he wasn't planning to make a film. But he found himself documenting conversations with Delay de la Beckwith, a KKK leader who'd physically attacked him in the 1960s, and the son of the man who assassinated black civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

That led to a film called The Last White Knight—Is Reconciliation Possible?: a no-holds-barred exploration of whether enemies can ever truly make peace with each other. Premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2012, it's a testament to Saltzman's willingness to engage with difficult subjects and his belief that film can open doors to understanding. You can watch it in full below, and I'd highly recommend you do so.

While in Mississippi, Paul discovered something else extraordinary. In 2008, Charleston High School had no official prom, and parents were organising two proms—one for white students and one for black students—outside the school. This led to another documentary, Prom Night in Mississippi, following students preparing for their first-ever racially integrated prom (in 2008!), following an offer of funding by local resident Morgan Freeman.

I found this film utterly compelling, and I'm clearly not alone. "I get emails thanking me for the films I've made," says Paul, smiling, "I've gotten emails saying your film changed my life. Whoa. That's why I make films."

The infinite nature of creativity

Paul has a theory about creativity that's almost spiritual: "Creativity comes easily to me... creativity is infinite," he says. "It's like love. Love is infinite. There's no end to it."

Rather than being a finite resource, he stresses, creativity breeds creativity. He gives the example of his documentary series Spread Your Wings, which followed 26 kids in 23 countries and explored creativity and cultural traditions. One episode featured 13-year-old Amy Hobby in Florida, who was learning photography from her father, a lawyer. Twenty-five years later, when Paul tracked her down to propose a follow-up series, he discovered she'd become a filmmaker herself.

"I say to her, 'How did you get into film?'" he recalls. "And she goes, 'You. Yeah, you.' Holy shit." When they met in Toronto—she was there for the film festival with her own work—"I put my hand out to shake hands with her, and she goes right past my hand into a hug."

Amy went on to make films with Ethan Hawke and hold a senior position at the Tribeca Film Festival. "That just tells you how creativity creates, how creativity unfolds, how creativity invents, how creativity opens doors," Paul says.

© Paul Saltzman. All Rights Reserved. "John and Paul were strumming their D-28 Martin acoustic guitars, singing fragments of songs, musically meandering through some of my favorites: Michelle, All You Need is Love, Eleanor Rigby, and others. I got my camera and after taking a few pictures through the chain link fence, I opened the gate and joined them."

One thing that can hold people back is if they struggle with formal training. And that was certainly the case for Paul, who got thrown out of university and spent years ashamed of it. But then, just six years ago, the same university got in touch and asked to collect his archives. "I was rehabilitated from a cast-off," he smiles.

"I've never been a book learner," he reflects. "I'm what's called a kinetic learner." This applies to everything in his life, not just filmmaking. "For example, my body knows how to play hockey better than I do," he points out. "When I can turn the brain off, when I can drop into the energetic flow, and it's not thought, I score goals that I don't know how to score. You know, if you said to me, do that again, I wouldn't know how to."

His message to anyone who doubts themselves, then, is clear. "Everyone has unlimited creativity," he stresses. "We have it beaten out of us. We are convinced out of it. So you need to silence the voice that says you're not good enough, not educated enough, not whatever enough." A Hollywood life coach told him something that stuck: "The negative ego always lies. That's its nature. And it always repeats itself because negative energy is non-creative."

What George Harrison knew

The most profound moment in Paul's career came during that week at the ashram in 1968, which is beautifully documented in his 2020 film, Meeting the Beatles in India. The four Liverpool lads had accepted him into their group, teasing and laughing together at a dinner table. During their conversations, George Harrison said something that shaped everything Paul's done since: "Like we're The Beatles, after all, aren't we? We have all the money you could ever dream of. We have all the fame you could ever wish for. But it isn't love. It isn't health. It isn't peace inside, is it?"

That realisation—that external success doesn't equal internal fulfilment—became Paul's north star. A Toronto lawyer who started 32 media companies told him years later: "When you get up in the morning, do that which gives you joy, and you'll always be successful."

By that measure, Paul has been wildly successful. He's made work that changes lives. He gets emails from strangers thanking him. Amy Hobby became a filmmaker because of him. His photographs of the Beatles hang in Liverpool Airport and galleries worldwide. Danger Bay entertained millions of children safely. His documentaries on race and reconciliation have sparked important conversations. He's passed courage along, just as he intended.

Today, Paul still sees new pictures everywhere. He shows me a photograph he'd taken that morning on his phone, from his bathroom window: it looks like something you'd see in a gallery. And despite sometimes enduring a rocky ride from the film industry, he still believes today that everyone has unlimited creativity waiting to be unlocked.

Ultimately, his career is proof that you don't need formal training. You don't need permission. You just need to trust the flow, silence the negative voice, and do work that gives you joy. And when you make work that comes from a place of joy and integrity, when you pass courage along to others, you create ripples that spread far beyond anything you can measure or control.