For four weeks before Christmas, New York's subway system became an unlikely laboratory for testing whether there's a middle ground between AI enthusiasm and AI rejection. It's a question that matters to every creative navigating this moment: Is there a useful third way?

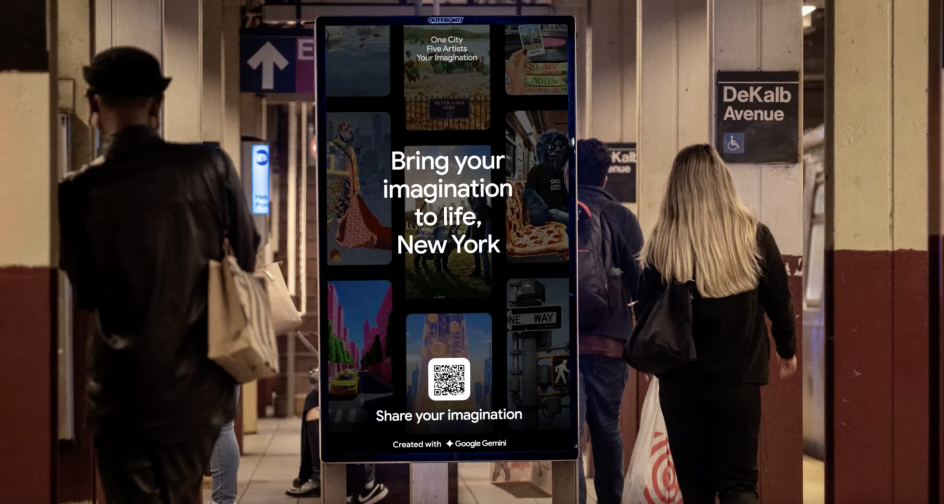

The "Imagine If" campaign, created by ad agency SuperHeroes for OUTFRONT Media and Google DeepMind, turned 4,000 digital screens across the MTA network into a moving gallery. The premise was straightforward. Subway riders could scan a QR code and submit an "Imagine If..." prompt—"Imagine if Brooklyn Bridge Park had off-leash hours for dinosaurs" was one early example—and receive an AI-generated visualisation.

Local artists would then transform selected submissions into polished video artworks, displayed across all five boroughs.

How it actually worked

SuperHeroes recruited five artists, one representing each New York borough: Lauren Camara, Ariana Cimino, Molly Goldfarb, Subway Doodle and Jeff Wave. These weren't AI specialists or tech evangelists. They were working artists with established styles and local followings, selected precisely because they represented distinct artistic voices.

Their role went beyond simple prompt engineering. They reviewed submissions from their respective boroughs, selected ideas that resonated, and used Gemini, Veo, Flow and Nano Banana to transform these prompts into finished artworks. The campaign culminated with a showcase on OUTFRONT's Two Times Square digital spectacular, the premium slot on Times Square's north end.

OUTFRONT's vice president and head of digital creative, Chad Shackelford, positioned the project as creating "a citywide experience that celebrates imagination as a shared act." Google DeepMind's creative lead Matthieu Lorrain described it as "truly participative art formats" demonstrating "human-AI partnership".

But the most revealing comment came from Subway Doodle: "As an artist, I was initially hesitant to use AI," he said. "But over time, I accepted that AI is here to stay, and I started exploring it. So when I got approached by SuperHeroes for this project, I was curious to explore how to use Google's generative AI as a tool for my art."

Why this matters

To my mind, that sentence—hesitant, accepting, exploring—matters more than any of the campaign's polished outputs or press release rhetoric. Because it's the creative industry's journey in miniature, stripped of the usual posturing.

Subway Doodle's path from scepticism to curiosity isn't a conversion narrative. It's a professional assessment. The tool exists. The brief requires it. The results are interesting enough to investigate further. No manifestos. No pretending this isn't complicated.

And that's precisely what makes this campaign worth examining as a potential third way. This wasn't a bottom-up exploration where artists chose to experiment with AI on their own terms. It was a top-down commission where the tools were already specified in the brief.

The artists weren't debating whether to use AI; they were figuring out how to use it well, on their own terms, with their artistic judgment intact.

What a cynic might say

Of course, there's an obvious critique here. A cynic might call it participation theatre: scan a QR code, get an instant visualisation, feel involved while the real creative work happens elsewhere. And this was, ultimately, a marketing exercise for Google DeepMind's Veo and Gemini models, complete with that slightly exhausting press release language about "collective acts of cultural co-creation".

Yet to me, even that corporate gloss feels instructive. Because let's get real: this is likely how AI tools will actually enter most creative workflows. Not through careful ethical deliberation or bottom-up adoption by sceptical freelancers. But through briefs where the tools are already specified, the budget is already allocated, and the question shifts from "should we?" to "how do we do this well?"

Key takeaways

If you're a creative director reading this while anxiously monitoring AI developments, the "Imagine If" campaign offers several practical takeaways that matter more than the hype.

First, the human contribution shifted, but didn't disappear. The artists weren't generating art from nothing: they were selecting submissions, interpreting community visions, applying editorial judgment about what would resonate with their borough's audience. These curatorial and interpretive skills became more valuable, not less, as execution tools became faster.

Second, AI tools worked best when solving specific creative problems rather than replacing entire creative processes. The artists used Veo to visualise community ideas, with all the judgment and craft that requires. The tool accelerated production but didn't remove the need for artistic decision-making.

Third, and perhaps most importantly: hesitation is reasonable, but avoidance is becoming expensive. The five artists who said yes to this project spent four weeks learning tools that will appear in dozens of future briefs. They built experience, developed workflows, and discovered practical limitations and possibilities. The artists who declined are, arguably, four weeks behind.

Conclusion

So is this a useful third way? Here's my belief: creative professionals are going to have to get comfortable with tools they don't entirely trust, made by companies they don't entirely like, producing work they can't entirely claim as theirs. That's not inspiring. It's not a rallying cry. It's just the state of play in 2026.

Is it a compromise? Definitely. But for working creatives facing briefs that already specify AI tools, pragmatic scepticism beats principled avoidance, at least when it comes to paying your rent. In other words, the third way isn't perfect, but it might be the only one available right now.