Tracing the design evolution of the BFI's LGBTIQ+ film festival, BFI Flare

In 1977, the National Film Theatre on London's South Bank programmed a month-long season called Images of Homosexuality. "It was very controversial but hugely successful," says Brian Robinson, a long-term BFI Flare Programmer. After that, he says "nothing really happened" in terms of presenting gay cinema, bar a couple of seasons here and there.

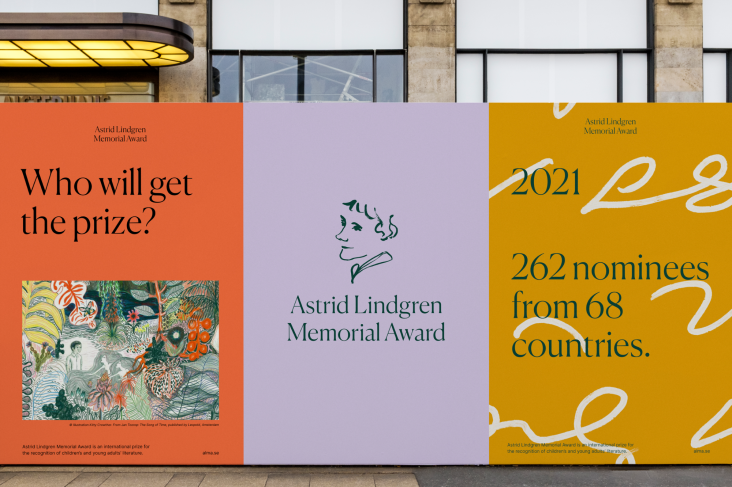

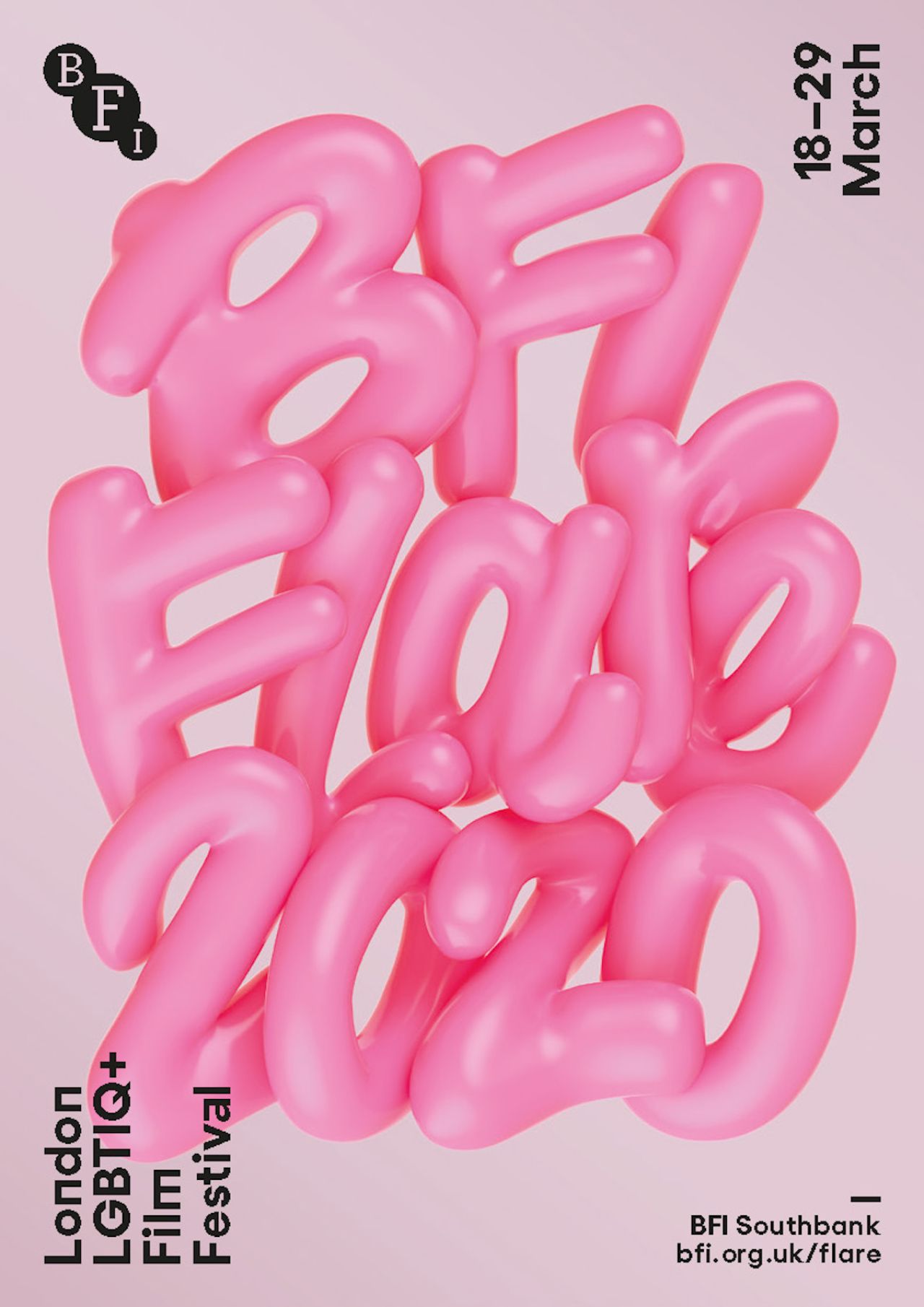

34th festival, 2020, by Studio Moross,

Then, in 1986, Gays' Own Pictures began when programmer Mark Finch put together a seven-day season of nine gay and lesbian features curated by Peter Packer of the Tyneside Cinemas part of the main NFT programme. At the time, the programme was undoubtedly controversial: as Robinson told Screen Daily, "Questions were asked in Parliament about whether this sort of thing should be funded at all. It was the summer of punk and the Queen's Silver Jubilee. It was a watershed in the history of gay cinema in Britain, which had no counterpart anywhere else in the world."

It was that season, 35 years ago, that spawned what's known today as the BFI Flare: London LGBTIQ+ Film Festival, at BFI Southbank (renamed from the NFT in 2007), which this year is screening online at the BFI Player. From 1986, the festival returned year after year, growing from its small beginnings to gracing the cover of the monthly National Film Theatre programme by its fourth edition and having grown from seven to ten days.

35th, 2021, by Studio Moross

14th festival

The journey from Gay's Own Pictures to Flare has been one of many twists and turns: "Naming has been a thing that's been quite fluid over the years, but eventually it calmed down and settled into the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival [in 1988]," says Robinson. It became BFI Flare in 2014, and by its 30th anniversary in 2016, audiences at all events and screenings over the eleven-day festival totalled 25,623.

Over the past 35 years of the festival, now known as BFI Flare, Robinson says the most significant change in the festival has been the availability of possible films to show. "In the early days, I would be struggling to find movies that checked all the boxes. Lesbians and gay men or bisexual or transgender characters often ended up dead in film. It was just part of the culture that somehow the reward for being actually different was that they died.

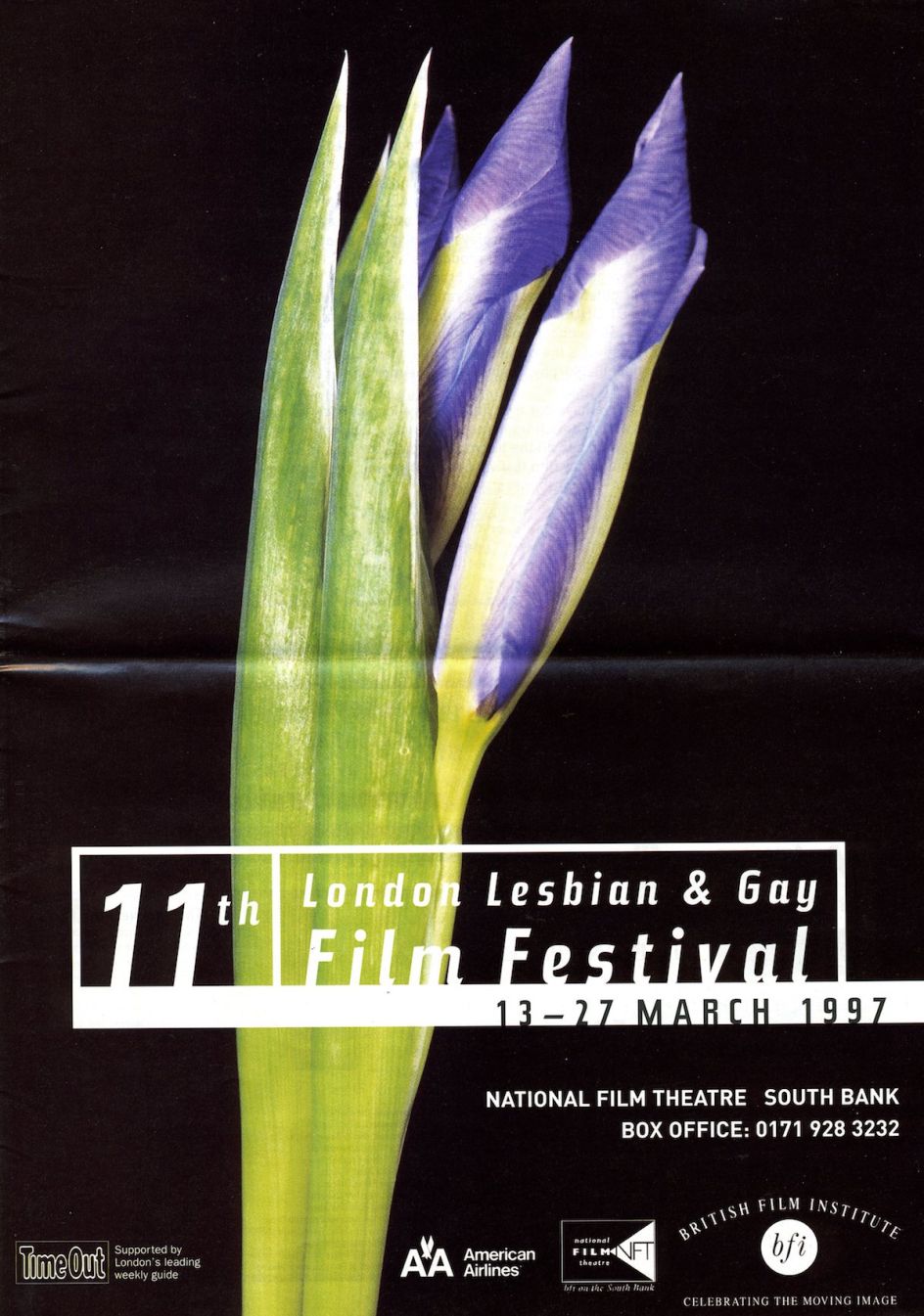

12th festival

"The great thing is that as the festival developed, there have been more and more films to choose from, and more skilled filmmakers came through, and there was more money put into production. There's been a growing professionalisation. In 1986, no one would have imagined that a gay film like Moonlight (2016) could be presented in the main competitions."

The film won numerous accolades, including the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, in 2017 and three Oscars for Best Picture, Best Supporting Actor and Best Adapted Screenplay at the 2017 Academy Awards. When asked about pivotal figures in queer cinema, Robinson names Canadian avant-garde filmmaker John Grayson, who made AIDS musical Patient Zero, as well as more big-name directors Todd Haynes and Pedro Almodovar.

It's fascinating to trace the festival's development through the design images used to promote it. The design work is primarily created in-house at the BFI. "For a considerable period, we just used a film still as an arresting image that was ready-made," says Robinson. When it was decided that they should move away from this approach and create a distinct image that "spoke to a wider audience," choosing the right one was "quite problematic," Robinson adds. "Do you have an image of women or men or both? How do you incorporate diversity? It all bubbled with the politics of identity and diversity, as we tried to get an image that would appeal to the most people."

The aesthetic trends of the time are often reflected in the chosen images. For the eleventh festival in 1997, the BFI Flare Festival campaign image uses a photograph of a flower. "It's very much informed by the work of Robert Mapplethorpe and Wolfgang Tillmans, which was very of the time," says Robinson. "It's a close up of something beautiful and appealing to give a sense of the artistic values of the festival being a little bit on the avant-garde side, but something aesthetically pleasing."

31st festival, 2018, by Studio Moross,

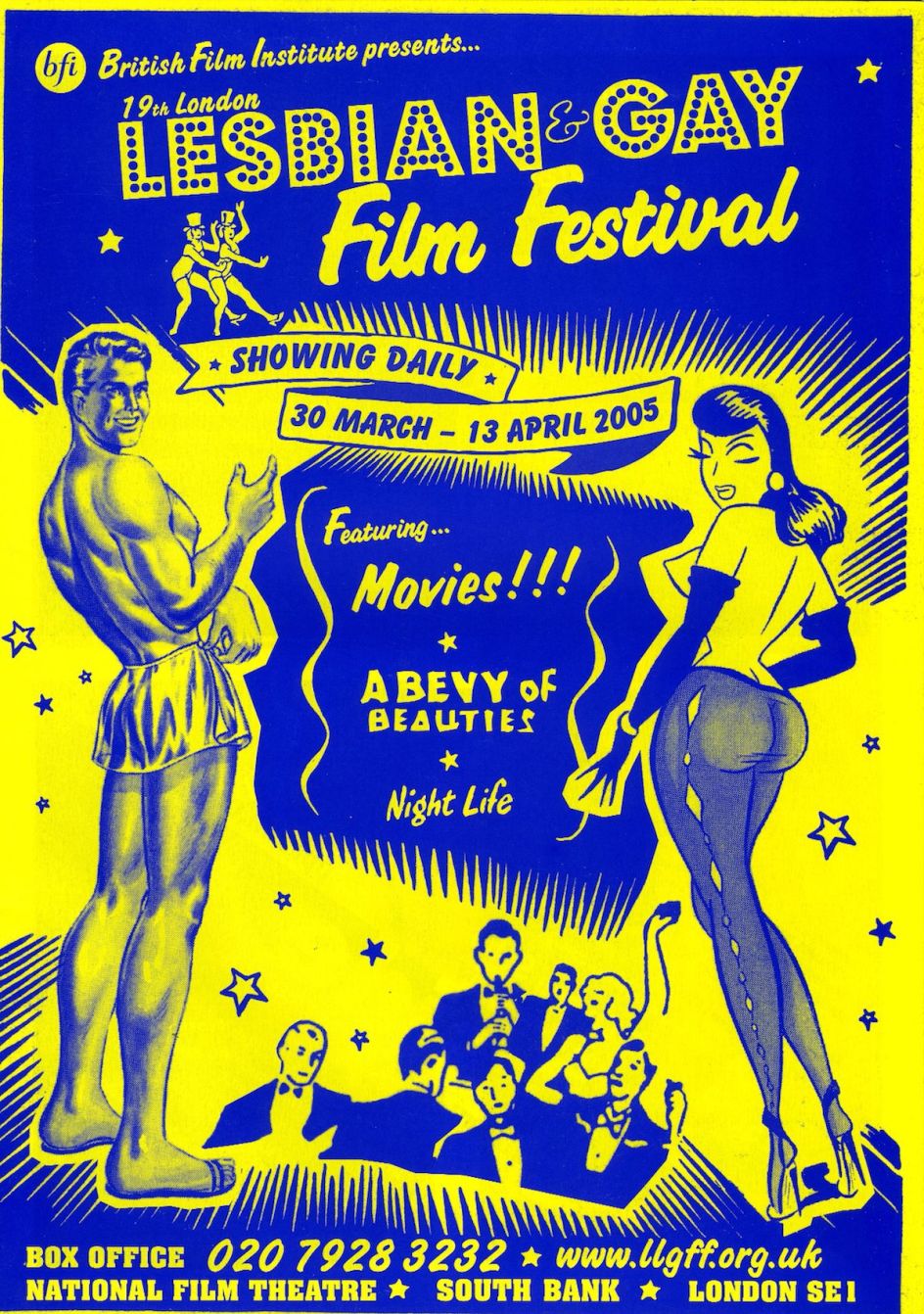

Other images courted more controversy: the 19th festival used a picture of a man in a transparent wraparound skirt, which caused "a bit of a tussle" with one of the festival sponsors; as did another image of a woman with a bit of breast exposed ("a bit too saucy for corporate values".) The skirt image was drawn from an early 1960s gay men's clothing catalogue: "you get a sense of the kind of the level of muscularity and a kind of wholesome sexual frankness," says Robinson, who adds that the designers did edit out the man's cigarette from the image, "not to be too censorious!"

Another highlight from the images over the years is the 22nd festival cover, which Robinson explains is "a homemade image from a photoshoot done on-site at BFI Southbank. Different members of the programming and administration wore different shoes, so there are socks and high heels, trainers. It's a genuinely oblique image that's quite colourful that speaks to performance and dressing up. That was in 2008, and by then, the festival was 15 days long, which is longer than the Cannes Film Festival. There were as many as 25,000 people coming to the festival. With those bigger audiences came more sophistication in marketing, and the internet became a very important thing that it hadn't been so much before."

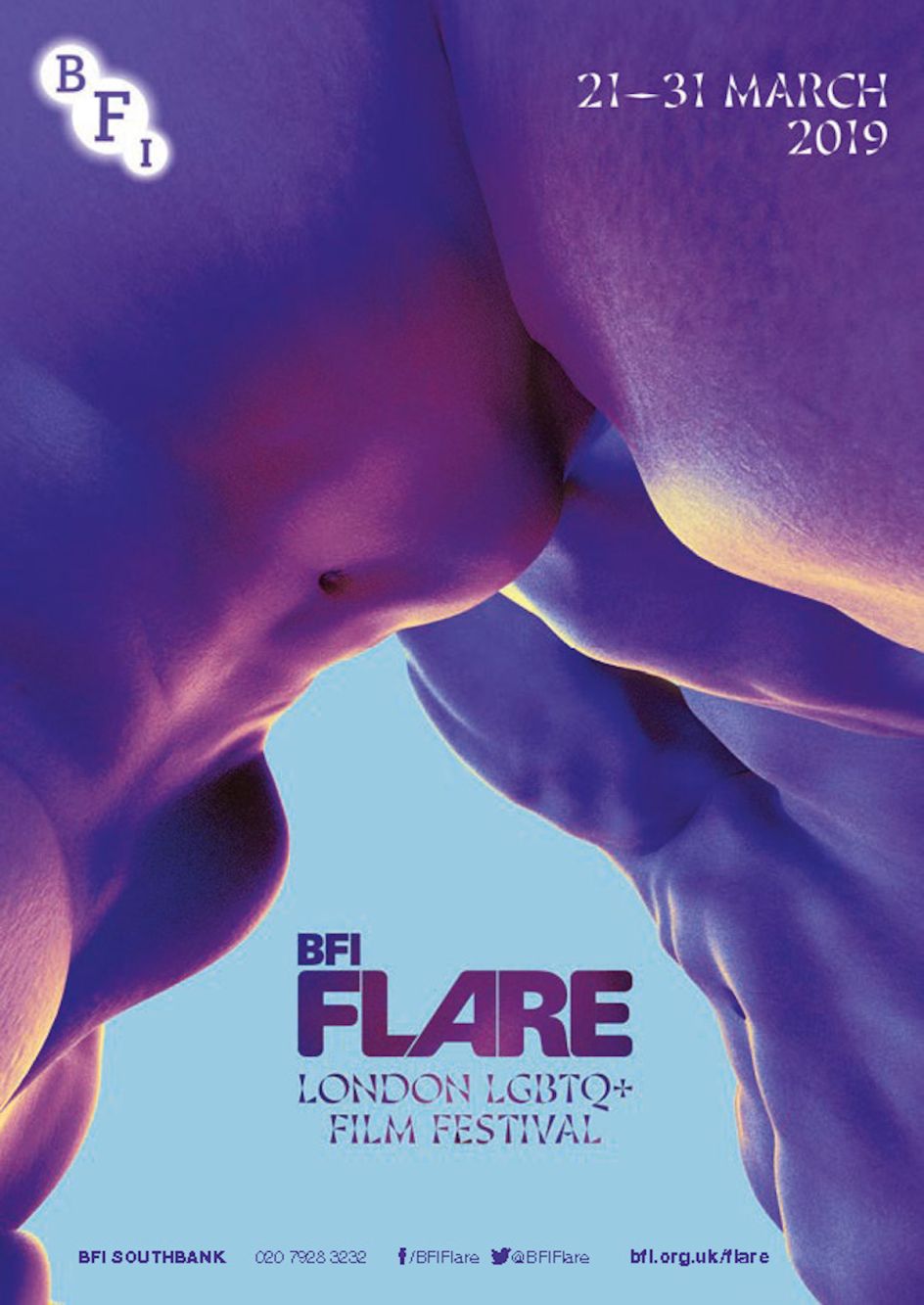

33rd festival, 2019, by Studio Moross,

32nd festival, 2018, by Studio Moross,

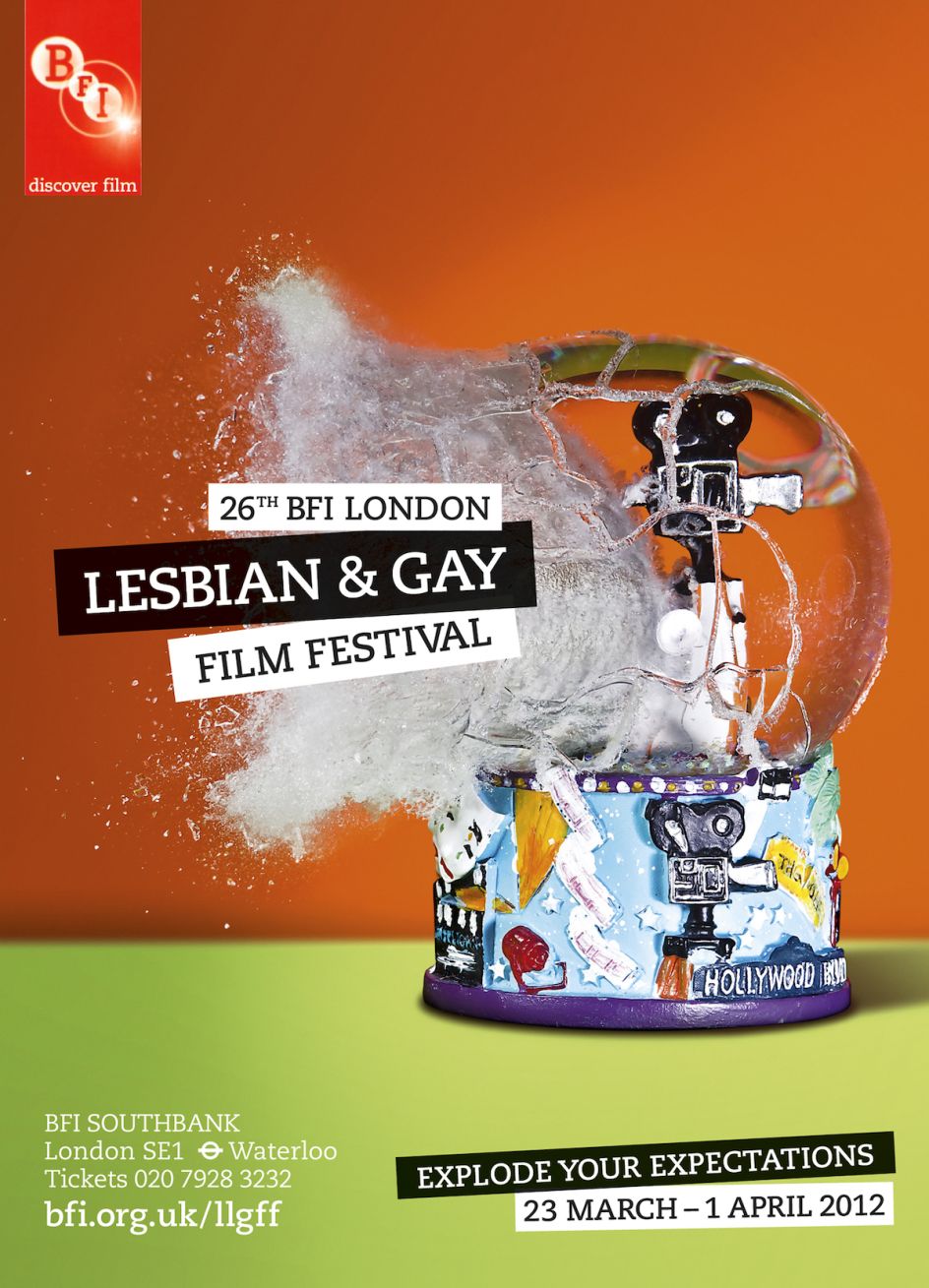

Throughout the years, BFI Flare Festival's images were largely worked on in-house with external designers brought in from time to time. In 2012, the team worked with freelance designer Sam Ashby, who they've continued to work with since. The image conceptualised by Ashby shows an exploding snow globe, shot by Alan Sailer, whose photography practice focuses on snapping objects that are exploding—he shoots them, with bullets.

"From my perspective, this is the first one that had a really clear creative concept," says Darren Wood, BFI Head of brand and creative. "We were asking, 'what's the tone of the festival? What do we want to communicate?' And we wanted to literally explode people's expectations: [the event] had become a really substantial moment in the film festivals calendar, not just a little niche, programming oddity. The stature of the festival now is very, very clearly different."

16th festival

8th festival

For the last five years of BFI Flare, the BFI has worked with Studio Moross. "It's been an incredibly fruitful relationship," says Wood. "Aries Moross has an incredible reputation, and we'd been waiting for the right project to come along [to work with the studio]. That team is so amazingly well suited to working on a project like Flare: they are all very plugged into the issues and ended up contributing to things like when we were working around changing the strapline for BFI Flare. They had a really strong opinion about that and really wanted to feed into that conversation. They're so plugged in to the issues and preoccupations of BFI Flare."

The first festival image the studio created was for the 31st edition in 2017, shortly after Trump was voted in and during a time of political and social turmoil that felt particularly piquant for the queer community. "I remember very clearly a meeting where we were thinking we should be protesting; we should be really putting our fist in the air and talking about our own position on this and protesting the current scenario." The image was born of that idea of resistance and so uses a pattern formed of protest-led iconography, including nods to the 1980s around things like Section 28, a Thatcherite piece of legislation that prohibited the "promotion of homosexuality" by local authorities, such as in schools. "I love that image in particular," says Robinson, who, along with the programming team, was consulted on things that they felt should be represented and which were important to them and their lives. "It's packed full of meaning," he adds.

18th festival

4th festival

Having had to make a very quick transition from the usual on-site event to an online programme for last year's festival (lockdown was announced just two days before it was set to open), the team had been hoping that this year's would be a more celebratory affair with a return to the BFI building. However, that wasn't to be, but the image still packs a sense of optimism.

"The last year had been very, very hard for everyone, but it's probably been particularly hard on people who were already feeling marginalised," says Wood. "We talked about the idea that we don't want the festival to feel dark and foreboding; we wanted it to feel like a celebration, almost a sort of emergence. We started to think about this idea of objects passing through a kind of chaos into light and order. It became a broader representation of the LGBTIQ+ community, moving from a situation that was very challenging into something more celebratory, something that was lighter and more orderly."

With three more days of this year's online programme (you can see all the films being screened here, there are still a few tickets available for the online film screenings and festival events; while a programme of 38 shorts is free to view for everyone in the UK on the BFI Player.

19th festival

29th festival