Orysia Zabeida tells us why memories are so imperfect, and what it's really like at Yale School of Art

Multidisciplinary designer Orysia Zabeida has managed a fair bit in her career – working with Björk, having a virtual natter with Tilda Swinton, acting as a design consultant for the Harvard Art Museums—despite having only recently having graduated from Yale.

Born in a coal-mining town called Tchervonograd in western Ukraine ("the name literally translates to the-red-town," she tells us), Zabeida is currently based in New Haven, Connecticut, and grew up on the island of Montreal in Canada.

Before Yale, Zabeida was the art director at the PHI Center and designer at the PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art in Montreal, where she worked with clients like Red Bull Music Academy, MIT Media Lab, three-Michelin-star Italian chef Massimo Bottura and Björk. In 2019, she collaborated with London's Goldsmiths University in an ICA-supported project to research the "relationship between organically formed artistic collectivity and institutional art world structures".

Her work is resolutely concept-driven, and as such, is never confined to a single medium: she works across typography, animation, web, print, "virtual spaces", participatory design and more.

It's also born of some fascinating insights, such as the way our memories are formed: complex and beguiling stuff, rendered all the more so through her visual explorations. We spoke to her about her process, Yale as a "colossal playground", the nuances of Ukrainian, and so much more.

How would you describe your practice and process?

I often start with a "what if...?" and stop when the result triggers an emotional response or a desire to engage. I lead with a concept and find the best collaborators, spaces, and means to express my ideas. I'm most excited by directions that have the potential of endlessly stretching, morphing, and adapting without losing their conceptual strength. My process is an ever-changing chain of iterations, tries, and errors led by curiosity and exploration of unexpected combinations of mediums.

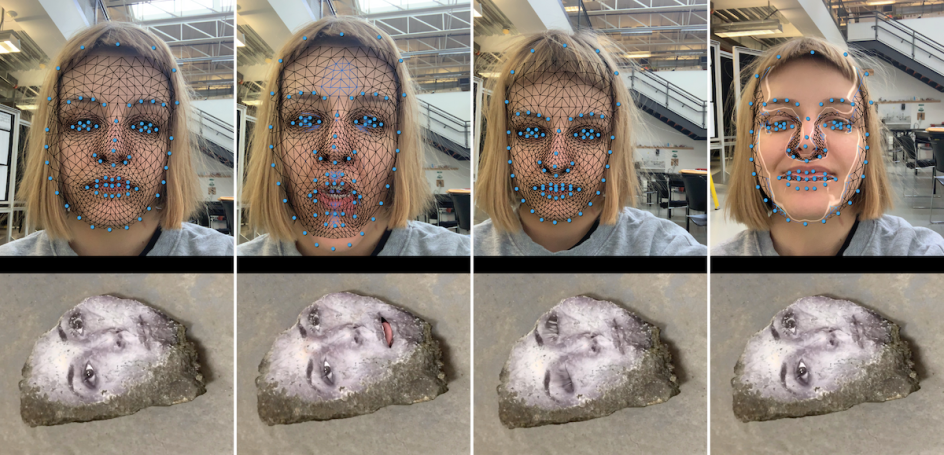

Talking Rock – Anthropomorphic experimentation with facial recognition

PHI Foundation for Contemporary Art team in Montreal Canada

What was Yale like? What were the most important things you learned there?

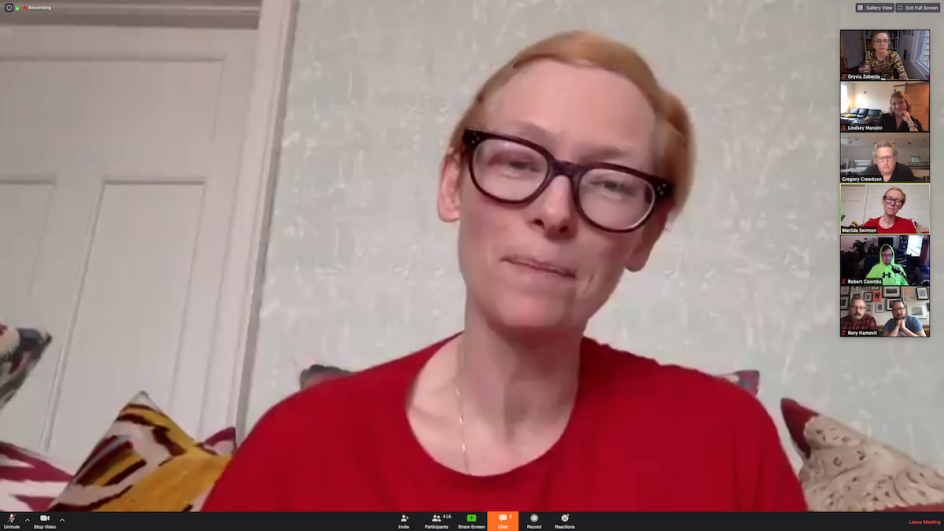

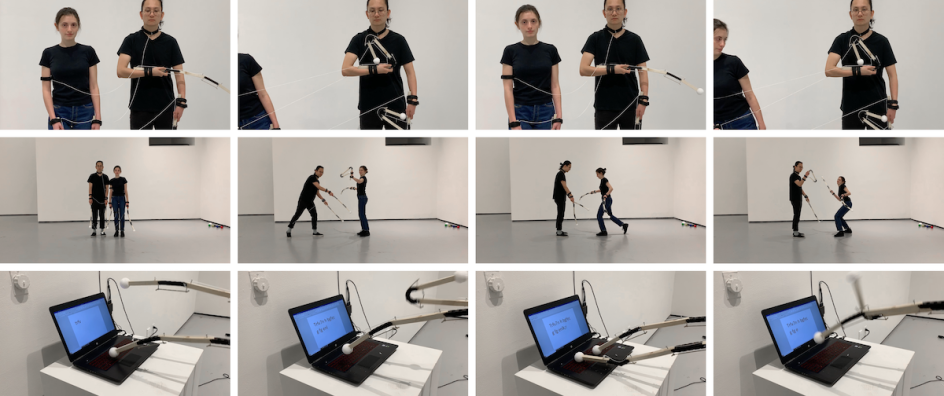

Yale is a colossal playground; it's the place to try everything you ever want to test. The best part of my education there was the multiple collaborations with students and faculty from other fields. Sarah Oppenheimer's workshop 'Sensitive Machines' in partnership with the Yale School of Engineering and Design was one of many highlights. My team created body extensions that explored the homology between human and mechanised gestures. We made finger extensions that could be moved by other parts of the body or by other human bodies altogether. Being at Yale during the pandemic also opened terrific opportunities to discuss with invited critics who would typically not accept to travel. Virtually meeting Matilda Swinton, Wolfgang Tillmans, and Irma Boom was amazing.

Tilda Swinton talking about the importance of an environment

Performance using Prosthetic Finger Extensions.

How has your background informed your practice?

My multilingual background (Québéçois-French-Canadian-Ukrainian-English) definitely tinted the way I think about design and accessibility. Each language has its own distinct universe, and each influences how we perceive the world around us.

One thing I love about the Ukrainian language is how we call the months of the year: each month is named after something happening in nature at that time. For example, April is Квітень, which is the word for Flower. November is Листопад which means Leaves Falling, and October is Жовтень which translates to Yellow. It is such a wholesome system of naming, but it also reminds me how mind-shifting and influential a language's way of seeing can be.

I think that very early, the mix of all those different alphabets made me create in a way that strives to connect beyond words and language. I believe that's also why I'm so attracted to music and sound work. It's a universal language that needs no translations; it's a visceral and direct communication channel. Here are a few images of a score made with bodies, exercise balls, and Ikea trash bins.

Performing Bin Ball Body (silent score) at the Yale Green Hall Gallery

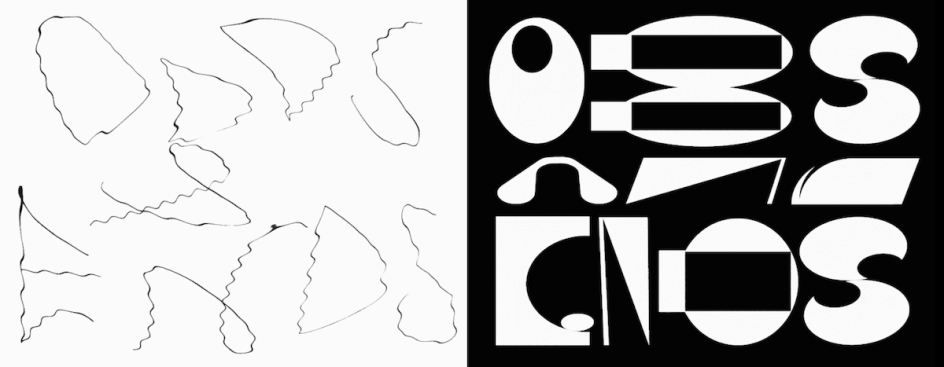

I'm interested to know more about your interest in kinetic typography. How did you come to be designing it for the Yale University Art Gallery?

I love Dia Studio's approach to moving typography. The other day, I stumbled on one of the founder's Instagram stories and saw him improvise on the piano. Everything made so much sense! Making good moving typography has a lot to do with understanding time, rhythms, and texture. It's a lot like improvising on the piano, building up tension, creating patterns, and surprising the viewer with visual changes of typographic tempo. Christopher Sleboda of the Yale University Art Gallery asked me to create a few kinetic works for the Odds and Ends Art Book Fair. Those were carte-blanche works I made with total creative freedom.

Yale University Art Gallery Odds and Ends Art Book Fair kinetic typography

Can you tell me a bit more about your video work?

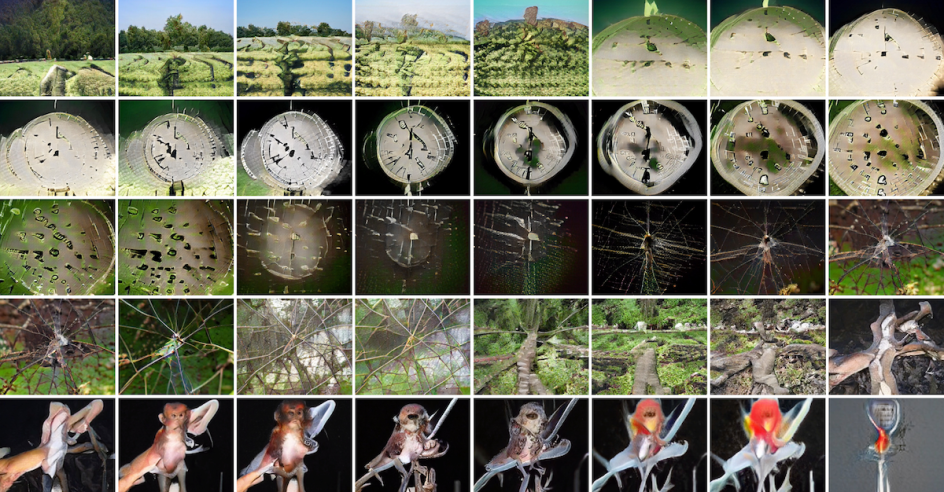

Yes! I've been experimenting with GAN (Generative Adversarial Networks) and love how the eerie visuals resemble what I would imagine a machine reminiscing would see.

According to Elizabeth Phelps, Professor of Human Neuroscience at Harvard University, about fifty per cent of the details of our human memory change in less than a year. I've learned that we subconsciously decide what to remember and what feelings to hold on to, and what's even crazier is that the visuals associated with those thoughts and feelings can be erased and completely interchangeable. As a result, our most significant memories, the ones that form the foundation of our life story, are not perfect recordings; they shift, grow, disappear and warp over time.

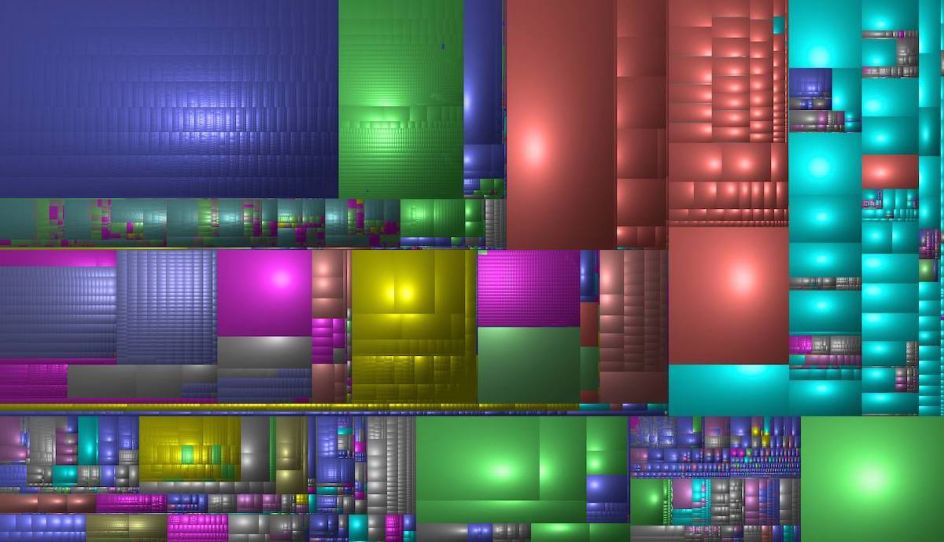

Screenshot of the artist's HD weaving digital matter

Generative adversarial networks (GAN) can learn to mimic any image. First, a network is trained to look for patterns and similarities in a specific set of images. Then, a second network judges the images. If it can detect a difference between the original image and the new copy sample, it sends it back to the first network. The first network then tweaks its data and tries to pass it through the second network again until the difference between the original and the fake is in-perceivable.

The result is imagery in which boundaries are indistinct, with figures melting into one another, creating distorted fluid collages. Here are some slides of my video recording the process.

What creatives do you admire in terms of either their approach to their practice?

I'm in love with Patty Chang's and Bas Jan Ader's video performances and mixed media art. I'm also a massive fan of Chris Marker and Agnes Varda's way of seeing. American filmmaker Les Blank's film 'Gap-Toothed Women' about society's shifting perception of the space between our front teeth and his film about garlic are also some of my all-time favourites.

Machine Memories – stills from experimentation with GAN

Digital Meditation–video performance still

Tell me more about your work's aim to "question how our feelings are affected by the devices we use daily and how our emotions can be amplified and controlled by designed environments and interfaces?"

Whether or not we are conscious of it, everything around us influences our mental state and general well-being. The silver lining of the pandemic made us all realise the importance of caring about each other, and as designers, caring means thinking about the consequences of the design work you produce. So I'm glad that buzzwords like "awareness" and "mindfulness" became even more popular and hopefully understood.

Pressure Points is an example of a project that subverts how we use standard interfaces. It's an augmented reality "healing" mask published on Instagram as a public face filter. The AR mask uses the interface to educate about reflexology and can potentially be a sort of self-help. The method, also known as zone therapy, is an alternative medicine that involves applying pressure with the thumb and fingers to heal other body parts.

Digital Meditation–video performance still

Pressure Points – AR face filter with self-help body healing points

Could you also expand on your interest in "routines and intuition" – they seem very opposed in a way?

We are constantly looking for the next event, the next experience, the next relationship. Always ahead, always leaning into the unfolding of our lives. It's as if our minds were constantly a little bit ahead of our bodies. So I feel like having a routine helps you be more in tune with your intuition. For example, in participatory design, to enjoy the unfolding of a project, you need first to create a framework with rules and parameters. There must be a balance between randomness and control. I think it's a little bit the same with our lives; then again, you decide if you want to have more of one or the other, but I think that both are necessary.

Routine – stills from a performance video at the LightHouse Beach

TOTAL SCREEN exhibition, UQAM Center of Design, 2021, Photography by Michelle Brunelle

What have you been up to lately?

I was recently invited by artist and educator Amandine Alessandra to serve as a juror for TOTAL SCREEN: Virality, Simulation, Surveillance and Implosion, an exhibition at the Montreal Design Center. The show is centred around the photographic work of French sociologist, philosopher, and cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard. It also features pioneering artists Adam Basanta, Penelope Umbrico, Mishka Henner, and Vaseem Bhatti. The exhibition will travel to the Venice Biennale in Italy, so I'm very proud of that.

More recently, I worked on the visual identity of On My Way, the Yale graphic design thesis exhibition showcasing the work of students who graduated during Covid-19. We created an interactive installation where the public could witness our text message exchanges. The virtual conversations were projected into the gallery's physical space during the run of the show. It was interesting to use the constraints of the pandemic to create a show that reunites people differently through screens and digital means.

TOTAL SCREEN exhibition, UQAM Center of Design, 2021, Photography by Michelle Brunelle