Robert Devereux on what we can learn from the 'anarchic' spirit of African art and why painting will never die

When the Heavens Meet the Earth, a new show at the Heong Gallery in Cambridge, challenges a lot of ideas and brings a number of important if uncomfortable questions to the fore.

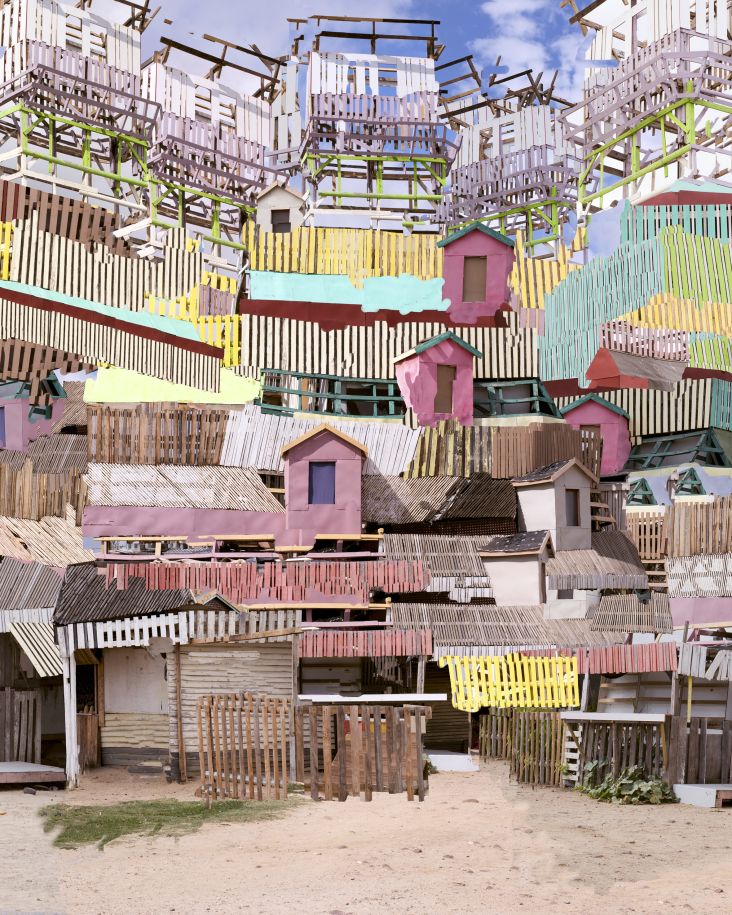

Mario Macilau Untitled 2, The Price of Cement. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

Presenting work from contemporary African artists, it, first of all, underscores something we're all rather aware of – the domination of the art world by middle-aged white men. Its work we'd likely never see were it not for the likes of Robert Devereux, the collector, and philanthropist whose collection has been whittled down for presentation in the show.

He is, of course, a white middle-aged man, but he's also one working hard to champion (and financially support) African artists, and practitioners based outside Africa whose roots lie in the continent.

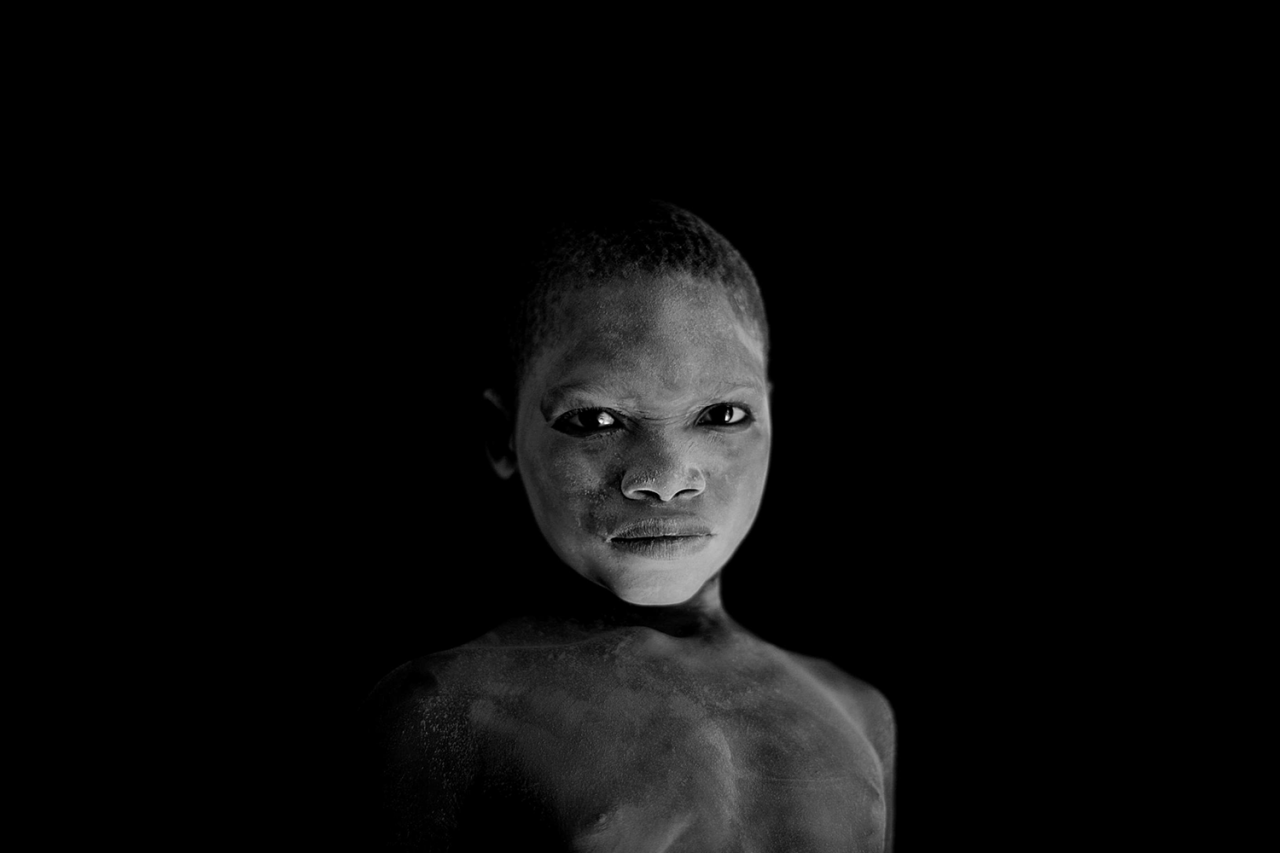

Zanele Muholi Miss D’vine II 2007. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

The idea of showing a personal collection in a public gallery, too, throws up a lot of questions: why do we trust one person's taste more than another? What is "taste" anyway? The mind boggles imagining these pieces in the domestic sphere, and I can't help taking myself on an imaginary Through the Keyhole tour of Devereux's many houses, where much of the work is usually on display.

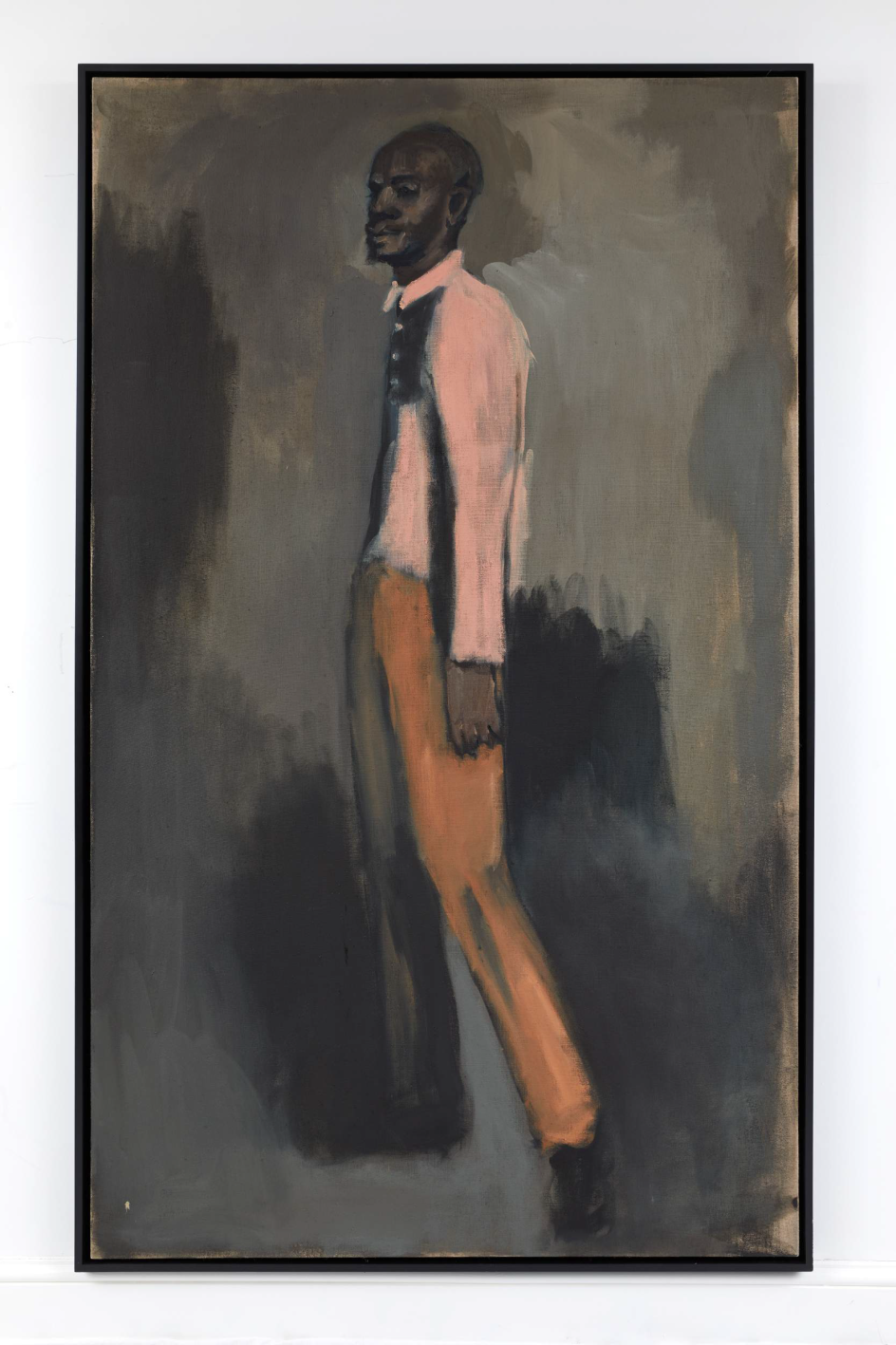

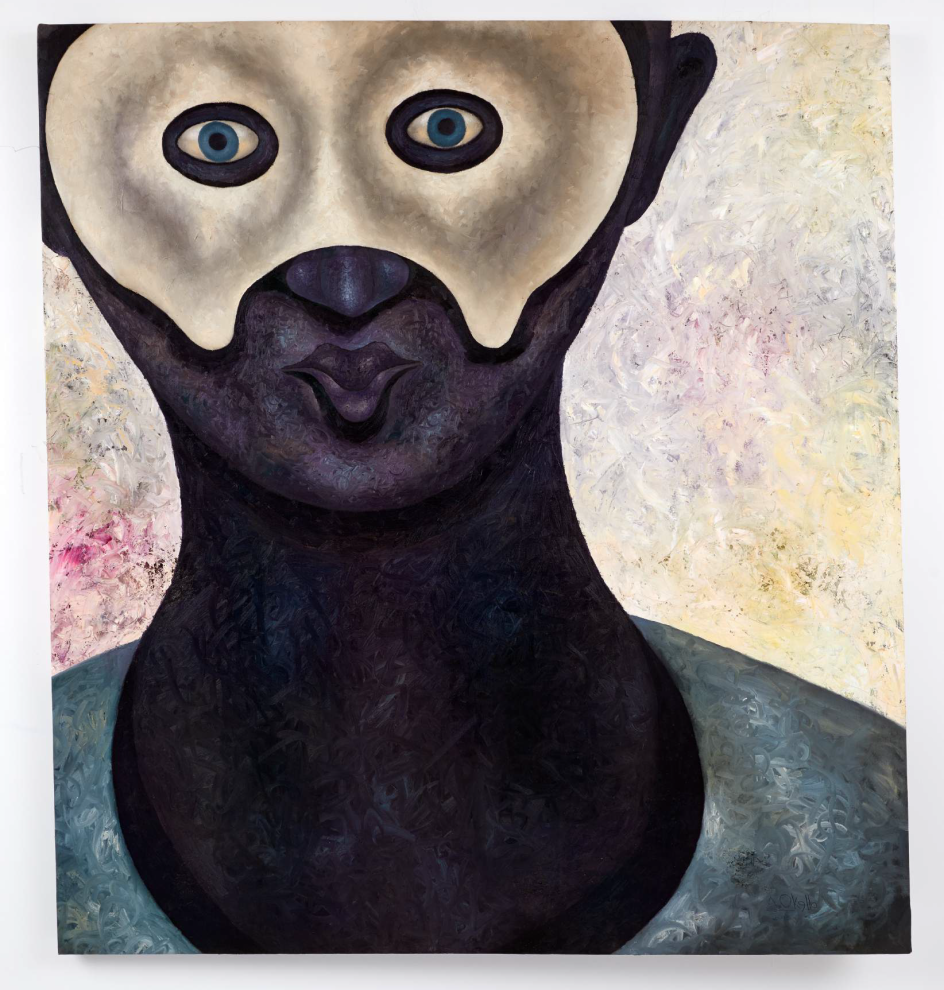

What does his family think of his taste in art? How massive must his walls be? It makes me realise how nosy I am, and really these thoughts shouldn’t detract from what's really a wonderful show. The work itself is superb, a glorious hotchpotch of established artists like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, who was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2013 and a slew of emerging artists from countries including Benin, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, and Zimbabwe.

Devereux is founder of The African Artists Trust (TAAT) which, according to the gallery, aims to champion artists who "challenge Western preconceptions of, and hegemony over, cultural expression and contemporary art".

He's an interesting chap: a former partner in the Virgin empire and Richard Branson's brother-in-law, and in 2011 he donated the £4million raid in the sale of some of his art collection – including sculptures and prints by the likes of Frank Auerbach, Anthony Caro, and Lucian Freud – to set up his charity supporting African artists.

For someone who clearly knows his stuff when it comes to art, he seems slightly baffled at a preview of the exhibition of his works – both at the idea of curating a show of it, and at the idea of being a collector itself. "If a collection is supposed to have some sort of coherence then I’m not sure this is really a collection," he muses. "I don’t really like the idea of being a collector in that it sounds sort of acquisitive and possessive; those things are so far away from the creative process that it seems rather unattractive."

Lynette Yiadom Boakye Erector, 2007. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery.

His instinctive and scattergun approach to collecting makes for a show that's wildly energetic and enthralling: an eerie cowhide and resin installation (Nandipha Mntambo's Enchantment) stands erect and proud like a regal spectre in the middle of the space; it mingles with arresting monochrome portraits of children with cement dust faces by Mário Maculau; a comedic and surreal ink drawing of a goat at an office desk by Ato Malinda; a sweet and naively rendered mixed media work by Richard Kimathi depicting a couple, the man delineated through a pistol on his crotch.

The job of making sense of Devereux's "random" collection went to curator Tessa Jackson, who says she was keen to "show the range of the collection – there are lots of different media and different approaches". She's certainly succeeded; and even more so, has made a densely hung show of varied and often wildly vivacious pieces of work somehow feel ordered, even calm.

The show's title is lifted from that of a sculpture by Nnenna Okore, an arresting thing which somehow has a feeling of weightlessness that belies the industrial metals and wires that form it. "The title of the show needed to not have a single purpose: When the Heavens Meet the Earth can be about the object, the material, or the ethereal – the things we can't see," says Jackson. "It's that sense of a huge contrast between the specific and the general."

Nandipha Mntambo Enchantment, 2012. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

The dangers of a show based on a personal collection is that it is, of course, the selection of one person, and one who likely chose much of it to put in their home: you'd fear there might be too much predilection for the decorative, a quiet eschewal of work dealing with messier, traumatic ideas around politics or oppression. But that's not the case here: we see the disquieting photographs of Ibrahim Mahama, which show the labels of goods sacks next to the tattoos of the men working with them, branded and marked as if they too were objects to sell.

Then there are the superb images by South African photographer Zanele Muholi, a gay woman in a country that's still worryingly hostile to the LGBT+ community: as recently as 2009 the country's then Minister of Arts and Culture Lulu Xingwana described Muholi’s portraits of nude lesbian couples as "immoral" and "against nation-building.” Despite this, there's a hopefulness about her work and portrayals of the queer black community.

The bold colours and the hard stares of her subjects seem to be telling the viewer that they will not be censored: in images, they cannot be oppressed. A duo of large-scale charcoal works by Peterson Kamwathi have similarly dark undertones, showing sombre figures – each slightly different but all very much the same – stood rigidly in a line. Each piece represents a different profession; the medical one is particularly haunting. "It's a comment on corruption," Devereux explains. "There are all sorts of interesting symbols you can read in there."

We spoke to Devereux about why it's so important we engage with African art, and what drew him to the creativity in the continent in the first place.

There's such a great energy to the space as you walk in, it must be lovely for you to see the work in a gallery. How and where is it displayed usually?

I have them mostly at home in West Sussex and London, but I lend my work as much as I can. I think the more people who can see it and the more it's shared the better. Though some sadly from time to time does end up in storage.

If you're showing a lot of work at home, how does that affect your decisions about what you collect?

Well as you can imagine it wouldn't be easy to install the Nnenne Okore [the vast wall mounted installation piece When the Heavens Meet the Earth] at home, which I've never done. I've never thought like that, although I think perhaps the reason I've not bought as much film is that I've never worked out how to display it.

I don't think I've ever really thought much about issues of display: a few years ago I bought a huge South African painting that's about eight meters wide and I can't possibly display that. I'm not always a very practical person.

What's exciting you about film work at the moment?

There's a lot of interesting film work about but I think doing this show has made me look at the collection in a different and slightly more thoughtful way. I suddenly noticed there wasn't a lot of films in there. I'm pretty agnostic when it comes to the medium.

I do love painting but no more so than any other medium. I'm so fed up with that argument that painting is dead, it's such a redundant argument that flares up now and again. Painting is just another way of an artist expressing themselves, and will always be a valid one.

Aida Muluneh No. 7 from the 99 series, 2013. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

Nnenna Okore, When the Heavens meet the Earth, 2011. Photo Jonathan Greet, courtesy the artist and October Gallery, London

There's such an eclectic range of work in show, what is it about a piece that makes it jump out at you and ultimately make you fall in love with it?

It's a good question that I don't really have an adequate answer to. I've got pretty eclectic taste: I love mark making I love draftsmanship like in the charcoal works by Peterson Kamwathi, but some things just respond to me. It's a dialogue: with any creative art form, it's a dialogue between the audience and the creator. Some works create a dialogue with me and some don't.

How do you come across the works in the first place?

They come from all over the place: artists' studios, auctions, galleries, people who just put me on to things. All over.

What is it about art of African origins that particularly interests you?

They're the nexus between two passions of mine: one of which is Africa and one is the visual arts, and I suppose it's to give my time some focus. I have other commitments of course so I can only devote a certain amount of time to the visual arts, so I need to narrow down that field of interest.

I like to understand a bit about the context and the environment in which the work is being made. We explain a lot of why we do in retrospect; now I say it's partly because I think African art is underrepresented and deserves more recognition and that's all true but that's not the only reason why I set out to do it.

Tell me a bit more about why you're so passionate about Africa.

One of the problems of explaining it is that you end up using terrible cliches and generalisations; but it's the whole look, smell, and feel of the place. It comes down to two things really – the land and the people.

I also love Scotland for similar reasons: man has trodden over probably all of Scotland and all of Africa but he hasn't left quite such an indelible footprint. I think places where man hasn't completely overwhelmed the natural environment really respond to me.

Again it's a ludicrous generalisation but I do find with the people there's an openness and spontaneity; and a kind of anarchy to the place. It isn't anarchy but I think here we live in a very mature society in many ways: it's rigid, but that means the room for manoeuvre isn't always there as it is in looser places. Mature isn't always a positive adjective.

Do you think that sort of spontaneity in the place and people come through in the art?

I think it does. I think partly because there's a lack of infrastructure in Africa so most of these artists didn't necessarily go to art school, although by now they've all been in a learning environment of some sort like residencies or exchanges. But they're much less institutionalised, so they have fewer preconceptions. They come to their practice from a more internal place with less external influences. I'm not at all criticising art school but they don't think about things like 'what is art'. They just do what they do, but that's not to say they don't do it thoughtfully because they do.

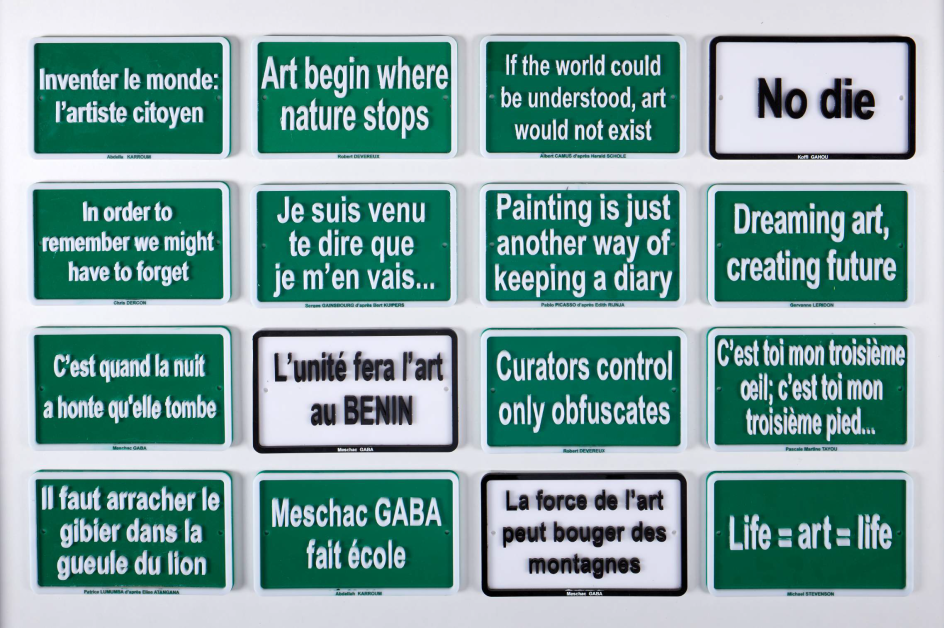

Meschac Gaba 16 plaques from Bibliotheque roulante, 2012. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

Anthony Okello X from Masquerade series, 2013. Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

Is there any sort of normal career trajectory for young artists in Africa? How does their journey differ from art school educated western artists?

There is to a certain extent a 'career path' to being an artist in the west but most African artists don't have that luxury. There's a strong artistic tradition in many African countries but all connected to ceremony or religion or some kind of cultural utility, but contemporary art is engaging in very different motivations and tools.

There aren't many families who are very supportive of African artists because it's not something they understand: 'what are you doing? This isn't a job! This isn't going to earn you any money!' So right at the outset there's a lot of resistance to becoming an artist. They tend to form communities and exchange ideas and practise but they're largely self-taught. I don't think it's easy being an artist anywhere but we're so privileged with funding and things like public institutions here, and they don't exist in Africa.

What's the commercial gallery scene like in Africa?

It's very thin on the ground, but is better than it was. In South Africa it's pretty good; it's not bad in Nigeria; it's getting better in Kenya but it's still pretty thin on the ground. Outside of South Africa and maybe Nigeria there's no real culture of contemporary art collecting that I'm aware of. But then things can change quickly: the number of contemporary art collectors in London is so different today than it was even 35 years ago - in the 1980s you could count the number of them on one hand.

Are there any African countries or cities you're particularly excited by art-wise at the moment?

It's always invidious to pick but I think Harare in Zimbabwe, especially if you consider the difficulties the country is going through and has been through. I'm dying to go back there. There's a gallery called Gallery Delta that's been going for 30 years doing extraordinary work, and a new gallery called First Floor. There are obviously other places too but those spring to mind.

Otobong Nkanga Trapped, Q.C. Yaba, 1991 Lagos from Filtered A'lemories 1990-1992.Copyright the artist Courtesy The Heong Gallery

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Grapes, 1989 Courtesy Autograph-ABP and The Heong Gallery

I know this is an awful question, but having all the work hung like this, have any works really jumped out at you as pieces you find particularly resonant? Any darlings?

I'm bound to avoid that question and the honest truth is no. One of the wonderful things about doing this show is seeing some work I live with and some that I haven't seen for ages, and there isn't anything that I've thought 'why did I buy that?' or 'what's that doing here?'.

What I love is that there's an extraordinary variety of work here and it coheres rather than conflicts. It's still quite calm and contemplative.

Having to select 40 works from 400 was always going to be a difficult task so I wanted to have as much as I could fit in here. Tessa [Jackson] is a properly trained curator and so she was worried it would be over crowded or overwhelming: this isn't how public galleries usually display their works. But I love it, I think it works.

What do you hope people coming to the show will take away from it? What do you think British artists can learn from the African artists you're showing here?

I hope in a way it might show that art is by is nature completely protean. I don't have any prescription, I think just show it and see what happens and hopefully, maybe it'll make people rethink their preconceptions about the value of art and what works and what doesn't.

What sort of preconceptions?

I don't really know what those preconceptions are. One might be to those who still think there's something in the argument that painting is a dead subject. I suppose the other is conceptual art: I rather reject the notion of conceptual art as a separate category of work, because I think all great art has a conceptual underpinning.

I suppose I want people to see that's there's room for all of it. I don't like categorisation, I don't like labels. I think that takes away from the whole point of human beings as creative animals.

When the Heavens Meet the Earth is on show at The Heong Gallery in Cambridge until 21 May 2017. Discover more at www.dow.cam.ac.uk.

for Creative Boom](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/06/063686a9a3b095b9b1f0e95df917ed4bd342be1b_732.jpg)

using <a href="https://www.ohnotype.co/fonts/obviously" target="_blank">Obviously</a> by Oh No Type Co., Art Director, Brand & Creative—Spotify](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/6e/6ed31eddc26fa563f213fc76d6993dab9231ffe4_732.jpg)

by Tüpokompanii](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/58/58684538770fb5b428dc1882f7a732f153500153_732.jpg)