Claudette Johnson on three decades of her black feminist art and what has changed since the early 1980s

One of the most arresting figurative artists working in Britain today, Claudette Johnson creates larger than life studies that are both intimate and powerful.

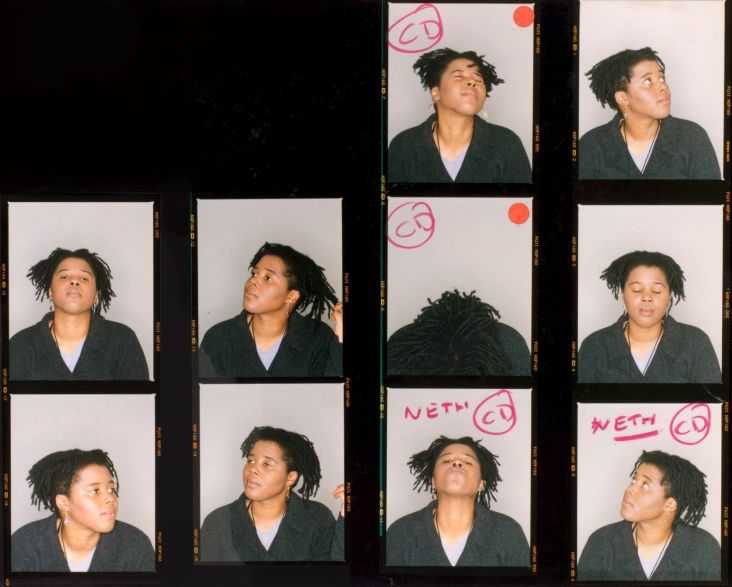

Claudette Johnson. Photo by Ingrid Pollard

An exhibition of her work at Modern Art Oxford, Claudette Johnson: I Came to Dance, will be her first solo show at a major institution in almost three decades and will feature 30 paintings and drawings in pastel, paint, ink and charcoal.

Throughout her career, Claudette has continually questioned the boundaries imposed upon black women. Musing that “a very small twisted space is offered”, Johnson works from life, inviting her sitters to “take up space in a way that is reflective of who they are”. This empathetic approach is rooted in Johnson’s deep sense of purpose. She asserts: "I do believe that the fiction of ‘blackness’ that is the legacy of colonialism, can be interrupted by the encounter with the stories that we tell about ourselves."

We chatted to Claudette about her new show, her career spanning three decades and what she feels has changed since the early 1980s.

Tell us more about your new exhibition. What can we expect?

The exhibition is made up of large-scale gouache and pastel works made over a thirty year period. The works are figure drawings and paintings some of which involved sitters who are friends or relatives and some which are drawn from my imagination or other sources such as newspaper images. All works feature black people; mostly black women. On visiting the show you can expect to see large bold images which I hope will intrigue and inspire.

How has your work evolved over the last 30 years?

Over the last 30 years, my work has moved from incorporating some quite abstract elements to having a giving greater force and presence to the people/characters that I am representing, primarily through scale. I think many elements are the same in that I still focus mostly on single figures within each work, I use the same materials mostly, though I have recently started using acrylic paint, and I still draw my figures larger than life so that they are, to some extent, monolithic.

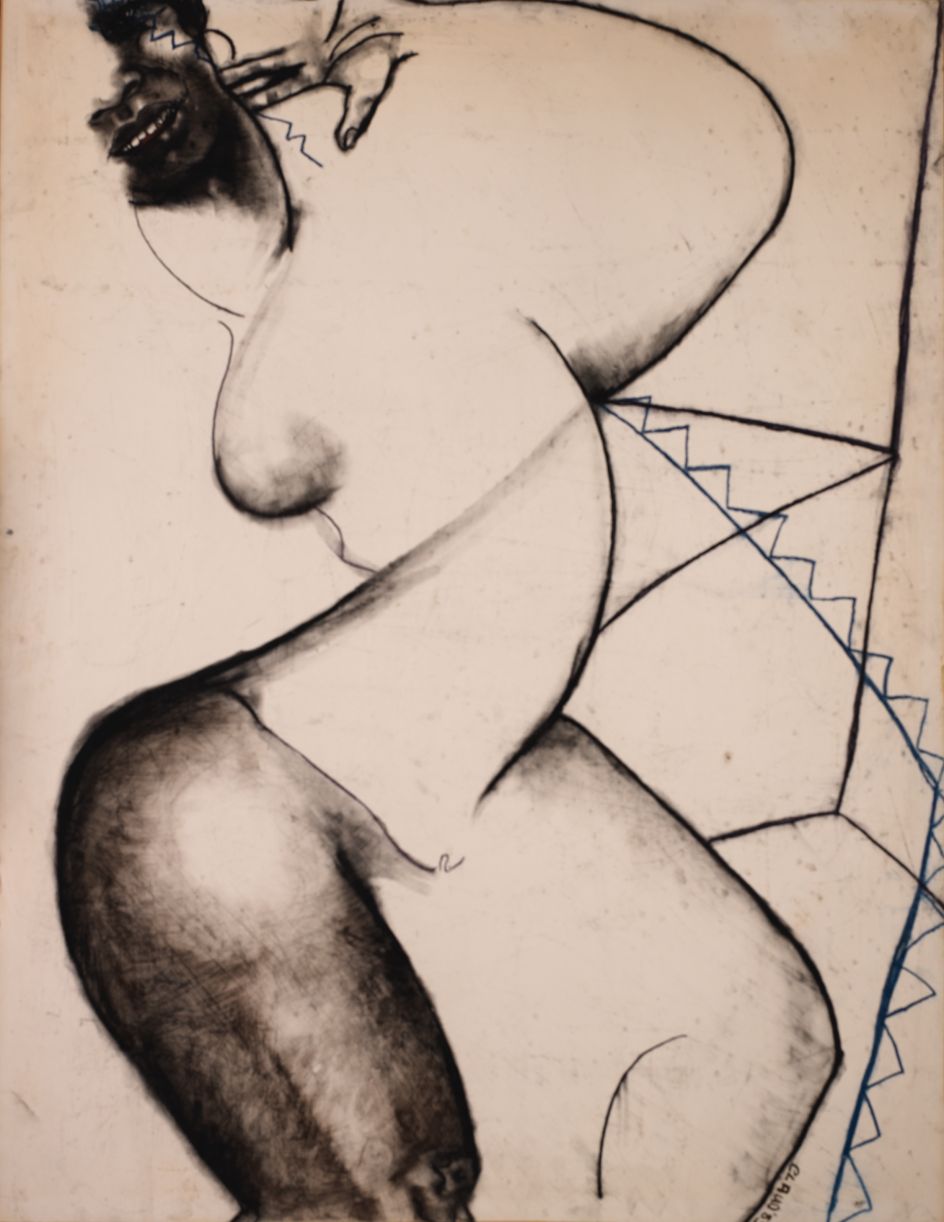

Talk us through, (Untitled) I Came to Dance. What was the feeling behind this painting?

The feeling behind I Came to Dance was of rage. The kind of rage that makes you want to do something just to show that you can. I was angry about the way that black people in general and black women, in particular, were marginalised, underrepresented and misrepresented. The drawing is parodying what black women are expected to do ie. dance, but it is also celebrating dance as an act of survival. I wanted the white spaces in the work to be as active as the linear forms in the work.

Symbolically, the fractured body in the drawing, containing only a curving line where the core of the body should be, speaks of the voids in our history, the loss of continuity of language and culture during the Atlantic slave trade. This is not the only possible reading of the work but it is where I started.

Your work has continually highlighted the boundaries imposed upon black women. Is it any different today compared to 30 years ago?

I think with the growth of social media, Instagram, Facebook and the many platforms for information sharing, there are more opportunities for black women to challenge the stereotypes that are still prevalent in the media.

In some ways, it can more difficult now to identify some of the ways that these ideas continue to circulate since superficially we are in a more enlightened age where gender and racial inequalities have been significantly reduced. Or at least, the mechanisms for challenging those inequalities are better understood.

Thirty years ago, there was no equal marriage, there were no black female members of parliament, I had never seen a black teacher or doctor, so there have been positive changes on that front.

Conversely, social media has the power to reinforce a status quo in which black people are never quite clever enough, pretty enough, powerful enough to make the grade. And that is very damaging.

Untitled (I Came to Dance) © Claudette Johnson

You were born in Manchester. Is that where you became interested in art?

Yes, I had excellent art teachers at my secondary school, Levenshulme Secondary Modern School for Girls. My teachers really encouraged and nurtured me. I also had a very good experience of studying for my foundation certificate in art at Manchester Polytechnic. Again, I was nurtured, encouraged and inspired by my tutors.

That said, I drew all the time as a child, wherever and on whatever I could find. I used to draw in the margins of the Radio Times and on newspapers. I didn't always have lots of materials so I would try and make my felt tips go further by using Pointillist – like circles that allowed me to create fields of colour instead of solid blocks.

In the early 1980s, you became a prominent member of the BLK Art Group. As a black female artist, what was it like back then?

I felt empowered; firstly by becoming a member of the BLK Art Group, then by becoming part of a large and supportive group of black women artists who showed work together, debated art together and learned from each other.

Your talk at the First National Black Arts Conference in 1982 is recognised as a formative moment in the UK's black feminist art movement. Tell us more about that time.

So much has been written about the convention that it's quite hard for me to add anything to what's been said! It was a very exciting time and I was overwhelmed by the response we got from black art students and artists all over the country who were prepared to travel to a city in the West Midlands to debate "the form and function of black art".

It completely obliterated the sense I had of being a solitary black art student with the remote ambition of becoming an artist. Until then, I hadn't realised there had been a Caribbean arts movement or earlier generations of black artists who had shown work in national art institutions.

My presentation at the convention was an attempt to demonstrate, through examples from my own work, that black women artists were exploring a different reality in their work, one that the mainstream art world was entirely unaware of. I felt that that the experience of being part of the first generation of British-born black women was driving a new force in art and leading to the creation of dramatically different images that were subversive, truthful and challenging.

Unfortunately, this led to an uproar in the conference and I was forced to bring forward the planned women's workshop so that the discussion could continue with those who felt it was important. Looking back, I wonder whether my concerns just seemed too small, too personal and too alien to the mostly male audience? Or perhaps it was just too close to lunchtime and everyone wanted to eat!

Standing Figure with African Masks © Claudette Johnson

Untitled (Seven Bullets) © Claudette Johnson

Back to your exhibition... much of your work features yourself or people you know. Are there any favourites? Can you talk us through the sentiment behind it?

I always find it easier to work with people that I know. Spending long periods, usually hours at a time, looking at someone, is quite an intimate act. Although my sitters are often people who are close to me, I am more interested in what they represent than in who they are, everybody tells a story.

It is for this reason that the names of the sitters are not included in the titles of the works. I am interested in saying something about drawing and the human condition. In a way, these are staged encounters and everything about the sitter's placing within the borders of the work, the angle of the head the position of the hands and the direction of the gaze, has been considered. I hope that over the course of looking at the work those elements will have a cumulative effect and that something will resonate with the audience.

Whose work do you admire?

I admire many Post-Impressionist Modernist painters from the early twentieth century and late ninetieth century. Toulouse-Lautrec, Suzanne Valadon, are painters I return to again and again for their approach to their subjects and their anti-naturalistic use of colour.

Lautrec is a particular inspiration because of the extraordinary quality of his line, his precise expression and his sympathy for his subject. I was also very influenced by the Austrian expressionist, Egon Schiele, in my student days. I wanted to emulate the energy of his line. His understanding of the geography of the body and how to position it on a two-dimensional plane is still instructive.

Amongst my peers, I really like Jenny Saville's huge figure paintings. In the early '80s, seeing the work of Eddie Chamber, Keith Piper and Donald Rodney and Marlene Smith were immensely exciting – they were foregrounding art politics, race and culture with highly intelligent Post-Modernist works.

I remember finding Sonia Boyce's work, Big Woman Talk, profoundly affecting. Lubaina Himid has been an inspiration, mentor and friend. I shall never forget seeing my first 'cut-out' on a small Ektachrome slide that Lubaina shared with me during the women's workshop at the First National Black Artists Convention in 1982. It was an acrylic on wood, cut out life-sized figure of a man with a paintbrush for a penis. It was acerbic, profound and funny.

There are too many artists to name who have been an influence or influential so this is not an exhaustive list!

Claudette Johnson: I Came to Dance at Modern Art Oxford will run from 1 June until 8 September 2019. Discover more at www.modernartoxford.org.uk.