Chris Fritton on skateboarding and covering 45,000 miles for The Itinerant Printer

Chris Fritton is not your average printmaker. He's behind The Itinerant Printer, an ongoing project that has seen him cover over 45,000 miles, visiting 125 print shops to make over 15,000 prints.

Inspired by the 'tramp printers' of history, Chris discovered an entire subculture – with a skill to trade, and a country full of opportunities, these wanderers would cover the U.S. and Canada, picking up work where they could find it.

As well as printing, Chris also lectures and hosts pop-up events at the shops he visits. With a background in creating skateboarding zines and an education in English Literature and Poetry, we were keen to find out more about Chris's intriguing career and travels to date.

Firstly, can you please tell us a bit about yourself?

I was born in a small city outside of Buffalo, NY, called Lockport. By most accounts, I had a pretty standard lower-middle-class childhood; I spent the bulk of my early years skateboarding, exploring abandoned buildings, and vacillating between getting into and staying out of trouble. I've spent most of my adult life living in Buffalo, but I've also lived in Maine and Southern California.

Believe it or not, my entire academic background is in English Literature and Poetics – ironically, letterpress printing has become my career, but I've had no formal training in art, design, or printing. I was lucky enough to attend the State University of New York at Buffalo & University of Maine at Orono, with incredible mentors like Ben Friedlander, Carla Billitteri, Charles Bernstein, Susan Howe, and the late Robert Creeley - people who are/were giants in the world of poetry and poetics.

How did you get into printing?

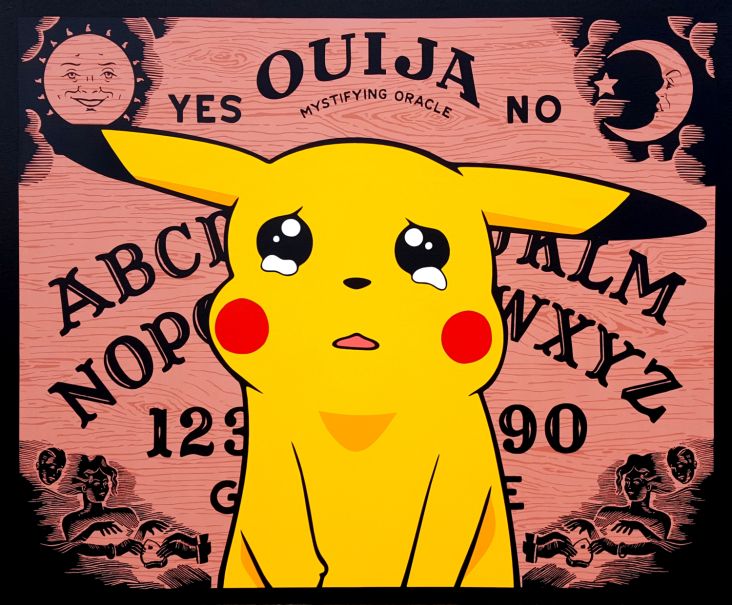

From an early age, I was producing punk & skateboarding zines, self-made publications that were cut and pasted together, photocopied, and stapled – they were quick & dirty, uncensored renditions – but as I got older, I started to produce my own books of poetry the same way. I was always looking for ways to improve the quality of my 'books', so at first, I turned to screen printing covers and digitally printing the guts.

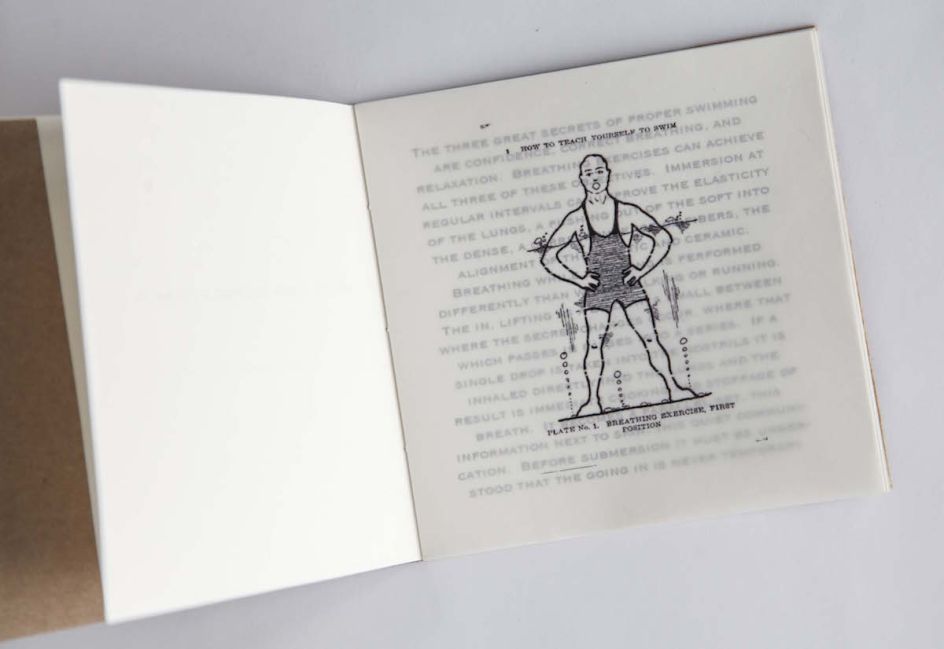

Through friends I discovered letterpress printing - at first, I would (again) just print the covers, but eventually, I graduated to typesetting entire works by hand, binding them by hand, even creating hardcover artist's books.

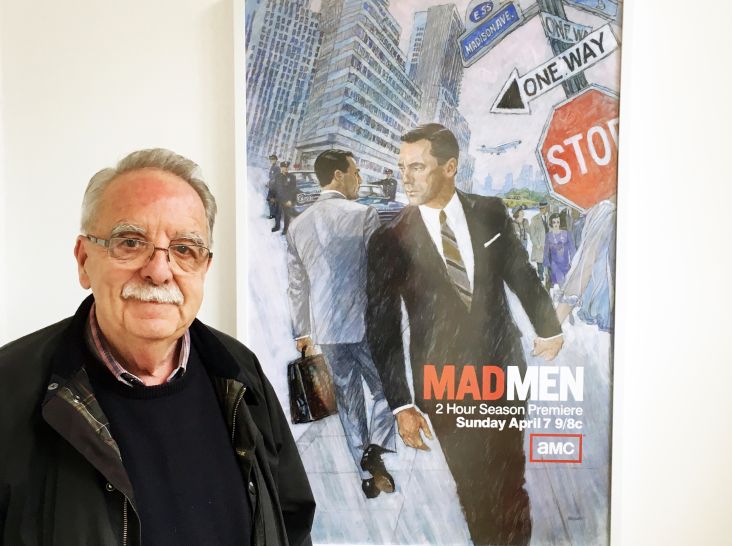

It wasn't until 2008 when I started running the studio at the Western New York Book Arts Center that I migrated away from books toward large-scale design work, creating event posters, gig posters for bands, and art prints. Prior to working at the Book Arts Center, I was fortunate enough to have access to a small letterpress print shop called Paradise Press owned by a friend and mentor, Hal Leader.

How did your Itinerant Printer project come about?

When reading about the history of letterpress printing, I'd occasionally come across references to 'tramp printers' or what many in the vocation simply called 'travellers'. I investigated further and discovered there was a whole subculture of itinerant printers – nomadic typesetters, linotype operators, and more.

They were card-carrying members of the International Typographical Union, and this allowed them to travel across the U.S. and Canada picking up work anywhere it was available. I became fascinated by the idea of itinerant printers traversing the continent, earning their keep, acting as analogue conduits for information. As they travelled, they brought tips and tricks about printing, as well as rumours: 'Did you hear so and so died? This shop is closed. Those two shops merged'.

Prior to radio and television, and with limited newspaper distribution, this was one of the fastest ways for that information to travel. Itinerant printers were revered for their skills, their erudition, and their cosmopolitan character, but they were also often derided as drunks and gallivants who swept into town and stole other union workers' overtime hours. While I didn't aspire to the latter, I was enamoured by the romantic notion of travelling the world printing, so I did everything I could to reinvent the concept of itinerant printing for modern times.

Can you briefly explain what you did and where you went?

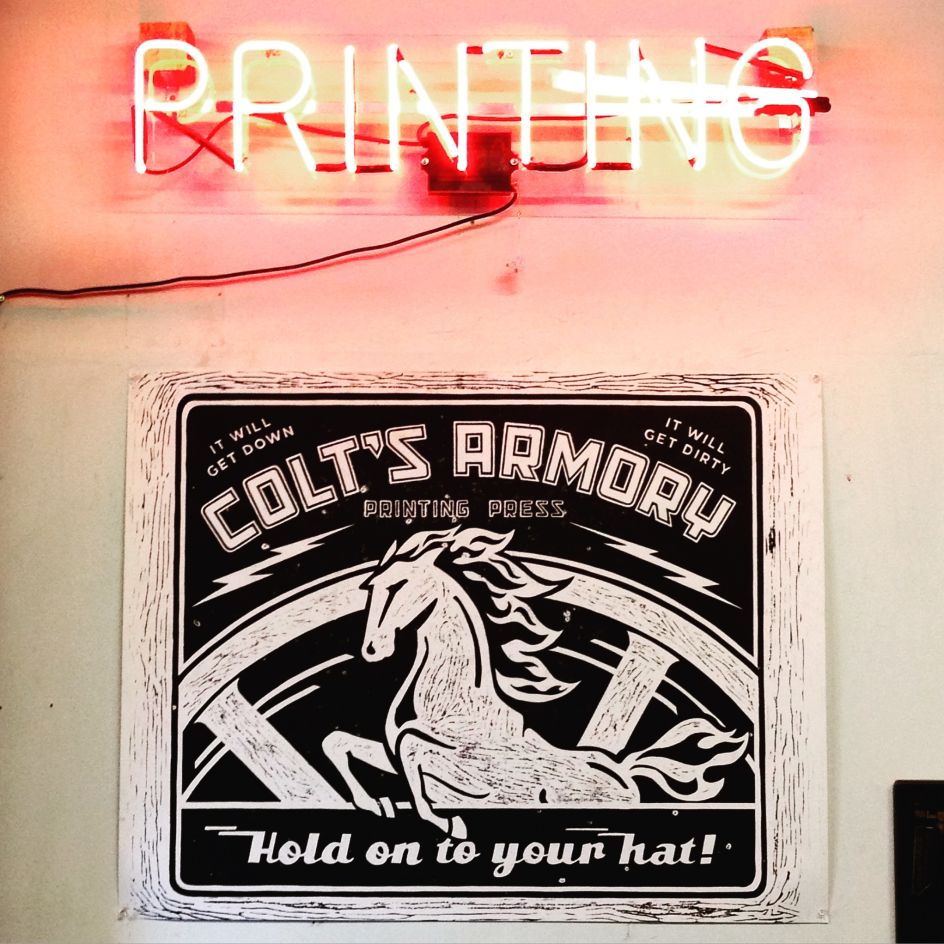

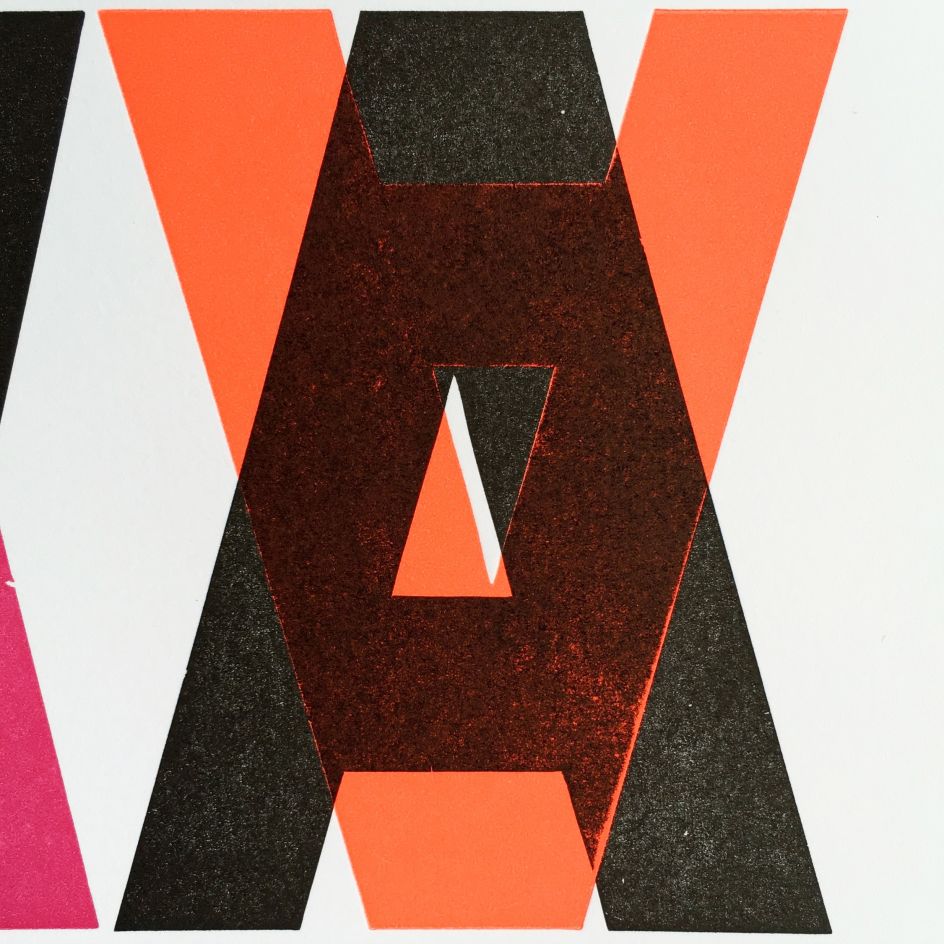

There's no longer a union to speak of, and I knew no one would be able to pay me a wage, so what I do is more akin to a mid-level touring band: I visit a letterpress studio for a few days, and the only thing I bring with me is paper and ink. I produce postcard-sized and poster-sized works at each shop, working exclusively from their idiosyncratic collections of wood type, metal type, border, ornament, and cuts. I visit schools and universities, privately owned shops, community-based non-profits, even hobby shops that might be set up in someone's garage.

Regardless of the venue, I stage an event during the visit with the help of my host – it could be a workshop, a presentation, a lecture, a pop-up shop or an exhibition. The money I make from selling prints, as well as honoraria from these engagements, is enough to perpetuate the trip, and these gatherings often act as catalysts for the local creative community. To date, I've covered over 45,000 miles, visited 125 print shops, and made over 15,000 prints. I've visited almost all 48 contiguous states and four Canadian provinces.

How did you prepare for the trip?

I started by contacting all the printers that I knew, asking them if they thought it was possible, and seeing if they'd like to be involved. The response I got was overwhelmingly positive, so I moved to the second stage of preparation: contacting people who had done similar projects, like my friend Kyle Durrie of Type Truck and Greg Nanney of Drive-By Press. Both of them had realised mobile printing projects, so I picked their brains for ideas, leads, possible pitfalls, and challenges that I might face.

After that, I started raising money via an Indiegogo campaign and securing a few sponsors - I knew that would make the project fiscally viable, but it would also create an outreach platform that got other people involved via snail mail, social media, and in-person interaction.

With all that out of the way, I learned to pack light, roll my clothes to save space, and take only the things I needed. Normally, everything I bring with me will fit in the trunk of a car. I do the trip in legs, which helps; I'll be on the road for two or three months, then take a few weeks off, then head back out.

Any particular highlights? Any challenges you faced along the way?

All the shops I visit are so different, but so much the same. They have amazingly diverse collections in terms of visual content, but at the end of the day, they're still full of type and letterpresses. I always use the analogy of a stick-shift car: if you know how to drive one, you know how to drive all of them, but it might take you a little while to get used to.

Working in a shop that I'm not familiar with is always a challenge, and every form that I make or print that I pull poses its own problems, but that's what I love about letterpress printing. Every day is a puzzle, and every day is a series of small-scale crises and resolutions. It's dynamic. I approached the entire project like I approach setting a form - it's about organising hundreds or thousands of pieces into a coherent shape.

All the people, all the shops, all the routes, the itineraries, the schedules, all of them were pieces that had to be fit into place. That being said, organising the trip was a challenge, but the toughest things I face aren't logistical, they're emotional and psychological.

I spent countless hours driving or flying alone, and I have almost unlimited time to think. Reflection is a great thing, but when it's pushed to the extreme, your thoughts can become obsessive. I stay with many of the printers I visit along the way, and it's their generosity and openness that have made the trip possible - but at the same time, that means I'm almost never alone unless I'm driving.

The nature of the trip is peripatetic, so it's inherently designed to create short-term, ephemeral relationships. That's the sustained paradox of the trip: I'm always alone, but I'm never alone, and I'm always close to someone, but never close to them. That being said, I'd have never visited places like Darien, GA where I printed at a refurbished plantation house called Ashantilly Press, or Menagerie Press, situated in a ghost town in Terlingua, TX where I printed in a hand-built adobe hut overlooking the Chisos Mountains. I've had the good fortune of experiencing so many incredible places and people, it sounds cliché, but it's hard to choose just a few.

Letterpress printing is a skilled job. Do you worry it will die out as online reading takes ever more prevalence in the modern world?

One of the reasons that I decided to do The Itinerant Printer project now is the renewed interest in analog art and the handmade. The DIY and Etsy revolution created a new generation of craftspeople, and the community they maintain is strong and diverse. After seeing hundreds of shops and meeting thousands of people on this journey, I have all the confidence in the world that letterpress printing will remain a viable art form; I'm especially thrilled by people who are doing experimental and abstract work - those novel ways of working with the medium are what will carry it into the future and keep the art form vibrant.

The lack of masters and mentors does concern me - as we've moved away from the infrastructure that the guilds and the unions provided (wherein an individual would be an apprentice, then a journeyman, then eventually a master and take on an apprentice of their own) craft in general, not just printing, has suffered. People have the interest, but because they are primarily auto-didactic, their skills can be subpar. That's dangerous territory for a trade like letterpress printing, where there are right ways to do things developed over centuries.

I believe that what letterpress printers do and how they do it may change or evolve, but the interest will remain as long as the equipment remains in functioning condition, and not despite the internet or digital technology - perhaps because of it; it allows printers to share their work with a wider audience and garner a client base. The digital revolution has inadvertently created a counterpoint which is the analogue revolution - in terms of print specifically, more books are being produced now than ever, and even many newspapers are growing, and although they aren't letterpress printed specifically, it does reveal a renewed and sustained interest in the printed word.

Would you say there is a shortage of letterpress printers in the world today?

Not in America. When I first embarked on the trip, people asked me if I'd even be able to find 100 shops. I was confident that I'd be able to find at least two in every state, but once I hit the road, suggestions, and requests poured in.

At this point, I'm very confident in saying that between community shops, privately owned shops, commercial shops, and hobby shops, there are probably between 2,000 and 3,000 functional letterpress studios in the U.S. The analogue revolution took place here a little earlier than it did in other countries, but there are dozens and dozens of shops in so many places around the world: Italy, France, the U.K., Australia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Japan, Russia, just to name a few. I think the numbers in the U.S. might level off, but we'll continue to see growth around the globe.

Do you believe that making by hand is more important than ever? And why?

I think that imbuing objects with value is always a worthwhile enterprise. Digital technology does provide results with a softer touch, but it requires real work nonetheless. I don't like to draw hard and fast boundaries between the digital and the analogue or see them as mutually exclusive, I like to think about the ways they can enhance one another. It's a two-way street, I can design things digitally and letterpress print them or execute them by hand, and contrarily, I can make something by hand and import it to be modified or used digitally.

Although I trade in ephemera often (paper goods with a short lifespan) and that's reminiscent of transient digital media, I do believe there's something special about a handmade object. Knowing that you're touching an object that was touched by someone else, that it was delivered, essentially, from their hands to yours, that's an intimate feeling. It's visceral, and it's meaningful specifically because of its visceral nature, but also because of its dissimilarity to what we encounter on a daily basis (digital media).

What key lessons did you learn during the project? Did you find that every printer you met along the way had new skills to teach or a slightly different way of working?

I've learned so many things – some are skill-based, some are elegant tips or tricks that solve persistent problems, but most are personal and emotional. I've learned to be patient. I've learned that not everyone is like me.

I've learned that people who share a common love of printing can still stand worlds apart in terms of politics or predilections. Before I left, I had a friend tell me: if you don't return from this trip changed, as a person, then you've done something terribly wrong. I think it's made me a better printer - the more that I share, teach, watch, listen, and absorb, the easier it is to turn to the press again.

More importantly, I think it's made me a better person. I've lived side-by-side with people very different from me, and it generates a greater capacity for sympathy and empathy. I've negotiated my own emotional struggles – times when I felt hopeless, felt like the trip was meaningless, or even felt like quitting. At every turn, there would be someone there that buoyed my spirits or told me to hang in there. I learned to appreciate people more - those who supported me at home, on the road, and even on social media – they became an integral part of a larger ecosystem that made this whole thing possible.

When your travels came to an end, did it feel strange to base yourself in one place for a while?

Technically, I'm still out on the road! I'm in Montreal, QC, right now. I take breaks on the trip, and it does feel strange to feel inert like I'm gathering moss. I get what the older itinerant printers used to call the 'itching foot'.

Do you believe that remote working is the future?

I love the community and I love collaboration, and there's an incalculable reward that stems from working with real people in a real place. I think that it's fantastic that digital technology, connectivity, and social media have made remote working possible, but I don't know if it's for everyone. I love the idea that people might be able to create a balance of remote/nomadic working and stationary, focused collaboration, regardless of their enterprise.

I have so many friends who work from the road or work from home now - virtual cities full of people that inhabit the ether, somehow getting their jobs done every day. It's magical, in a way. But, it's important to note that remote working is dependent on some people being stationary - I wouldn't be able to work from (or on) the road if others weren't maintaining brick and mortar establishments. The same goes for designers, typographers, journalists, and photographers as well - remote working wouldn't be possible for them unless someone maintains a home base - a production facility, a newspaper, a magazine, etc.

For someone looking to get into letterpress printing as a career path, what would be your advice to starting out?

Find someone to apprentice under. It's a trade, it's a craft, it's an art. You need someone to show you the finer points and steer your education. A printer friend said once, and I'll never forget: 'learn the rules so that you can then break them with grace'.

After that, do what I'm doing now: find a way to pursue a journeyman time in your career - learn from other printers, see their shops and their workflow, and use what you learn to set up your own space in the way that works best for you. I'd also advise that aspiring printers in large cities take advantage of community shops that share equipment - letterpress is perhaps the heaviest of arts, and not everyone has the room in their home, garage, or basement to create a studio. Utilise those resources to make what you want and participate in the community - it's often a better solution than hoarding equipment in a space that's too small or unmanageable.

You’re also a lecturer – do you find that the younger generations are as keen to learn trade skills, such as letterpress printing, as generations gone by? Or is there resistance towards being ‘hands on’?

There's definitely a shock and a lack of familiarity, but I haven't encountered any resistance - the process intrigues most students, and after experiencing it first-hand, they become fascinated by its unique attributes.

Many of the students I encounter hunger for something 'real', something that doesn't involve digital technology, and printing can be the perfect thing for future designers, typographers, and artists to engage with - they're forced to connect with the physicality of building images, respect space as real space, and the actuality of objects. I think that being face-to-face with the legacy of your media immediately fosters respect for its practitioners and their work.

Where is the most creative place you’ve been?

There isn't one place, but to me, there does seem to be a formula: some of the most creative places I've been are mid-sized cities that have strong art, music, and theatre scenes, ones that encourage collaboration between media and share resources.

In small businesses, print shops included, three seems to be the magic number. When three people are involved, they have the time, energy, and varied skill sets to get an incredible amount of work done. Being in a mid-sized city also allows you some freedom to 'steer the ship' and watch your cultural production have a measurable impact on the community.

I'm sure people would like to hear that it's any place where hundreds of designers live and work, but I have amazing experiences in workshops and teaching settings with non-designers. Designers can be hampered by too many choices, and they're often stuck with the paralysis of ambivalence. Accountants and other 'non-creative' people tend to make quick, decisive selections that produce beautiful results.

That leads me to believe that the most creative places aren't necessarily the ones that are supposed to be, they're the ones where people are given tools, freedom, skills, motivation, and an audience.

Who or what inspires you?

Constraint. Letterpress printing is all about creativity within constraints, and I love solving the problems that come along with those restrictions. When writing poetry, I always give myself constraints, and when I'm printing, those constraints are already there, inherent to the medium. I'm working with a finite group of objects trying to create infinitely variable results.

What are you currently working on?

Finishing up The Itinerant Printer project! Only about 20 places left to visit in the Northeastern U.S.

What’s next?

The Itinerant Printer book. The whole project will culminate with a coffee table book that features all the people, places, and prints from along the way. After that, maybe I'll quit printing altogether. Go out with a bang. No – I'm kidding. I'll set the scene for a global version, I hope, and maybe in a few years when we catch up, I'll be writing the second book.