'I don’t really have creative block in my vocabulary,' Cevdet Erek on his performance at Berlin's Berghain

Cevdet Erek's work is a beguiling combination of design, architecture, performance and sound, working together to produce something bigger than just the sum of those parts.

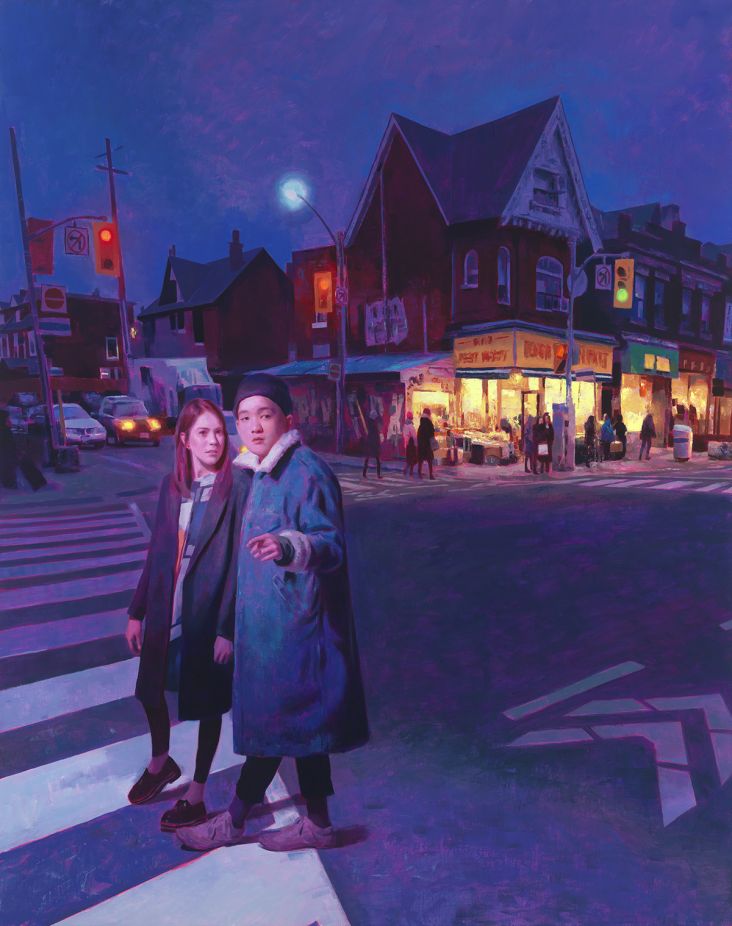

ÇIN (2017), Cevdet Erek. Pavilion of Turkey at the 57th Venice Biennale, installation view, Photo Credit: RMphotostudio

Last year, the artist represented Turkey at the Turkish Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, showing a site-specific installation piece that explores ideas around memory and experience. His work often showcases how innovative use of creativity in all its formats can tell important stories about Turkey's political and social tumult and volatility.

This week, Erek will be performing at Berlin's hallowed Berghain club as part of the CTM Festival, which runs until 4 February at venues across the city.

Erek, who originally trained as an architect, is mostly based in his birthplace, Istanbul, but last year took to Berlin to create the searingly visceral, powerful record Davul, formed from "extracts culled from hours of solo drum improvisations recorded over two days," with "no editing or overdubbing". The release is out on Subtext, a label based in Berlin that works with artists that explore the boundaries between sound, special concerns and other artistic practices. The label has previously worked with artists including Emptyset, Paul Jebanasam and Roly Porter.

We caught up with Erek this week ahead of his show to find out how sound and visual art can work together and how he gets over creative block.

How do you think people's expectations differ in seeing art in a biennale context?

Some expect to see something that shocks them or something they've never experienced before, or just the opposite: something fitting into their worldview, art or taste – there are hundreds of artworks that might fit that route in the group shows and National Pavilions. Some expect a particular media. They are blind, if not deaf, to others. Some ask, "what has that artist brought from their country"? Some have no expectations: they just walk to the next one. Who knows, maybe they fight with their expectations.

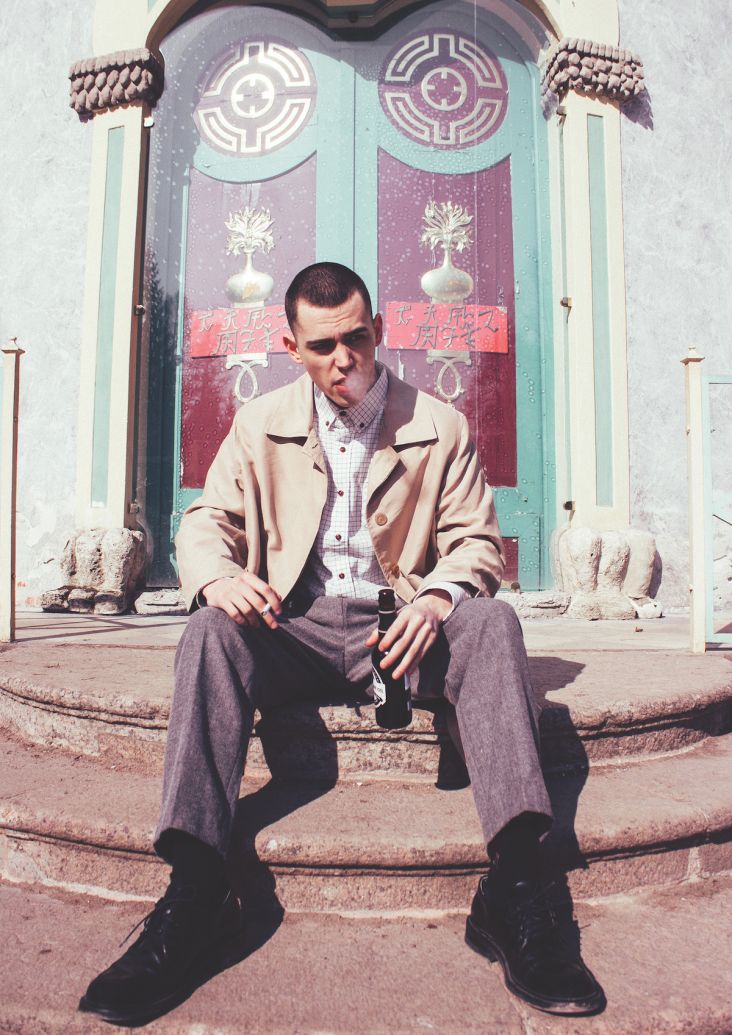

Cevdet Erek press shot,Theresa Baumgartne

ÇIN (2017), Cevdet Erek. Pavilion of Turkey at the 57th Venice Biennale, installation view, Photo Credit: RMphotostudio

How far do you feel you are a "Turkish" artist? What role does national identity play in your work?

I am from Turkey and spent more or less all my life in Istanbul. Everything – language, location, history, among other things – affects any person's life so that it will do on someone involved with arts as well. But I wouldn't define myself as a 'Turkish Artist'. I don't wake up in the morning with that feeling.

Your new album Davul comprises "extracts culled from hours of solo drum improvisations recorded over two days in Berlin," with "no editing or overdubbing", according to your website. Can you tell us a bit more about that process? Was it liberating? Have you worked like that before? Why Berlin?

Yes, I am quite used to improvisation, but this was the first full-length solo release, so it makes it a first and very special. After years of doing recordings for my own, for the band, friends, other artists, installations, films, etc., it was finally me and a drum in the studio and making a full-length record. We made it in Berlin because James of [record label] Subtext proposed that: we already released the soundtrack that I did for the film Frenzy in 2015 with Subtext.

Then we decided to make a full-length. Then I proposed to make a solo Davul thing, and James liked the idea and proposed the studio which he had already worked in before, Tobias Ober's Bonello Recording Studio. I was on the way to Venice for a long stay in preparation for the Biennale, then took my drum with me and went to Berlin afterwards. Then, of course, the Venice Biennale work ÇIN and Davul talked to each other:

zang tumb tumb

drummer in the battlefield scene

a momentary hesitation in her hand

may the war end

Those words are from my text included in the ÇIN brochure. Yes, it was liberating. I just flowed on the drum for two days. Then I listened to it, and in the end, there were approximately four hours of recordings, and then I cut the tracks. There was no editing other than the beginning and end.

Cevdet Erek press shot, Rachele Maistrello

ÇIN (2017), Cevdet Erek. Pavilion of Turkey at the 57th Venice Biennale, installation view, Photo Credit: RMphotostudio

How does your process differ when working on a purely sonic piece of work instead of one that brings in visual and architectural elements?

Recently I mostly haven't been doing too many "purely sonic pieces" – a radio piece, a radio live performance or a record – if the medium doesn't ask for that. I can't imagine the drum album as a sonic-only piece even: the object. The instrument hung on the body and is so strong that I can't reduce it to only sound. Soon we are going to release the 10" of ÇIN, which includes all sounds used in that spatial work and was formed together with quite heavy architectural construction.

The final result in the record is purely sonic (if you don't really count the record cover, insert etc.). Still, all come from a spatial piece – sonic, visual, architectural, performative etc. I think the record is a good example: even though it feels like a sonic only thingie, as a kid coming from times of tapes and records, I was so much more amazed by the total work, both the record cover and its content.

What's the ideal working environment for you?

I'm in Berlin at the moment, working in a hotel room, which is fine for now, but then I'm back at my home/studio in Istanbul, or my small room at the University next week, where I have hundreds of personal or functional things within easy reach. I don't think there is an ideal space, but mostly for me, it would be silent or a chosen soundscape until a person to talk to arrives.

ÇIN (2017), Cevdet Erek. Pavilion of Turkey at the 57th Venice Biennale, installation view, Photo Credit: RMphotostudio

How do you get over a creative block?

I just Googled what creative block means. I don't have it in my vocabulary. If I understood it well, a block seems difficult to get over temporarily. If I am aware of it, I look in another direction and walk through different blocks to another area or a field and don't look back for some undefined time.

I would already be behind the previous block and run back to it in time. If that doesn't work, I walk around, check the other blocks that might send a signal, or search for another free field.

What do you think the artist's role is in 2018?

To not try and answer all the questions, keep working on those pieces that are in construction and whatever's needed—the same as any other year.

What can we expect from your performance at CTM?

I won't try to define someone's experience. The facts are that it'll be a person with a hanged bass drum played with at least two sticks, a few microphones, amplification, a huge sound system, Berghain and people at night. Start, stop, start again.

](https://www.creativeboom.com/upload/articles/86/862919952c0ad18439004228895a431dc6e45ffc_732.jpg)